FYI. Someone in stroke leadership needs to assign this to a brilliant researcher to figure out if this can be used for stroke recovery. But since there is NO leadership in stroke; NOTHING WILL OCCUR!

Radixin: Roles in the Nervous System and Beyond

1

Department of Neurology, New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers University, 185 S. Orange Ave, Newark, NJ 07103, USA

2

Department of Neurology, New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers University, 90 Bergen Street DOC 8100, Newark, NJ 07101, USA

*

Authors to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Biomedicines 2024, 12(10), 2341; https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12102341 (registering DOI)

Submission received: 16 September 2024

/

Revised: 10 October 2024

/

Accepted: 14 October 2024

/

Published: 15 October 2024

(This article belongs to the Section Neurobiology and Clinical Neuroscience)

Simple Summary

Radixin

is a cytoskeletal-associated protein, a member of the ERM (ezrin,

radixin, and moesin) protein family. Radixin plays important roles in

cell shape, growth, and motility after activation by phosphorylation of

its conserved threonine residues. Radixin functions as a relay in cell

signaling pathways by binding to membrane proteins and transferring the

cell signals into the cells. The pathogenic function of radixin has been

found in central nervous system diseases, peripheral nerve injury, and

cancers. We recently found significantly altered radixin in Schwann

cells during elevated glucose, suggesting that it may be related to

diabetes-induced nerve injury. As a result, the insight review into the

roles of radixin and its associated cell signaling pathways may

facilitate finding novel therapeutic targets for associated diseases.

Abstract

Background:

Radixin is an ERM family protein that includes radixin, moesin, and

ezrin. The importance of ERM family proteins has been attracting more

attention, and studies on the roles of ERM in biological function and

the pathogenesis of some diseases are accumulating. In particular, we

have found that radixin is the most dramatically changed ERM protein in

elevated glucose-treated Schwann cells. Method: We systemically review

the literature on ERM, radixin in focus, and update the roles of radixin

in regulating cell morphology, interaction, and cell signaling

pathways. The potential of radixin as a therapeutic target in

neurodegenerative diseases and cancer was also discussed. Results:

Radixin research has focused on its cell functions, activation, and

pathogenic roles in some diseases. Radixin and other ERM proteins

maintain cell shape, growth, and motility. In the nervous system,

radixin has been shown to prevent neurodegeration(This is good!) and axonal growth(Not clear; are we preventing or assisting axon growth?) .

The activation of radixin is through phosphorylation of its conserved

threonine residues. Radixin functions in cell signaling pathways by

binding to membrane proteins and relaying the cell signals into the

cells. Deficiency of radixin has been involved in the pathogenic process

of diseases in the central nervous system and diabetic peripheral nerve

injury. Moreover, radixin also plays a role in cell growth and drug

resistance in multiple cancers. The trials of therapeutic potential

through radixin modulation have been accumulating. However, the exact

mechanisms underlying the roles of radixin are far from clarification.

Conclusions: Radixin plays various roles in cells and is involved in

developing neurodegenerative diseases and many types of cancers.

Therefore, radixin may be considered a potential target for developing

therapeutic strategies for its related diseases. Further elucidation of

the function and the cell signaling pathways that are linked to radixin

may open the avenue to finding novel therapeutic strategies for diseases

in the nervous system and other body systems.

1. Introduction

Radixin

is one of the ERM family proteins, including ezrin, radixin, and

moesin. ERM proteins, functioning as the link that bridges the actin

cytoskeleton and membrane proteins, play very important roles in

maintaining cell shape and motility through physically anchoring

membrane proteins and assisting the signal transduction of

post-translational processes [1].

ERMs also act as intracellular scaffolding proteins to relay the

extracellular stimuli to the intracellular compartments of the cells [2].

In addition, ERMs have been demonstrated to regulate membrane dynamics

and protrusion, cell adhesion, cell migration, and cell survival [2].

The broad cellular function of ERM implies that the deregulation of ERM

holds potential roles in the development of diseases. In this article,

we discussed the biological activity of ERM with a focus on radixin in a

variety of diseases.

2. Activation of Radixin

2.1. Radixin Structure

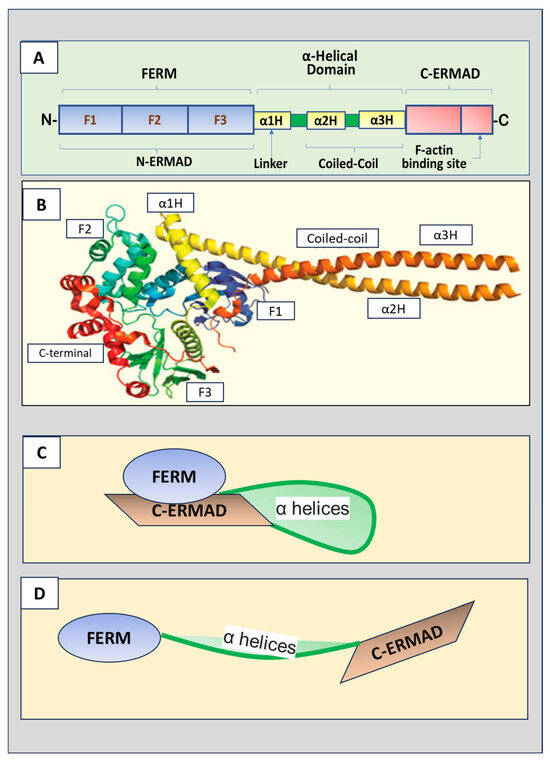

The three ERM proteins possess similar structures, containing three major domains (Figure 1A,B).

The amino terminus (N-terminus) is the four-point-one, ezrin, radixin,

and moesin (FERM) domain that consists of F1, F2, and F3 subdomains

(represented by A, B and C subdomains, respectively) [3].

The FERM domain, also named the N-terminal ERM-association domain

(N-ERMAD), is the site for ERM proteins to interact with cell membranes.

The FERM domain can bind to membranes, integral membrane proteins, and

scaffolding proteins [4].

A central helical domain comprises three α helices, α1H, α2H, and α3H.

α2H and α3H form a coiled-coil structure called the α-helical domain,

while α1H acts as a linker region that connects the FERM domain and

α-helical domain. The α-helical domain can bind to and mask the FERM

domain. The carboxyl-terminal (C-terminal) end contains the F-actin

binding domain, also known as the C-terminal ERM-association domain

(C-ERMAD), which can bind the FERM domain and F-actin.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic ERM (ezrin, radixin, and moesin) protein

domain structure. The N-terminus is the four-point-one, ezrin, radixin,

moesin (FERM) domain that has F1, F2, and F3 subdomains. The FERM

domain, also called N-terminal ERM association domain (N-ERMAD), is the

site for ERM proteins to interact with the cell membrane. A central

helical domain comprises three α helices, α1H, α2H, and α3H, which

functions as a linker region connecting the FERM domain and an α-helical

domain at the central portion of the protein. The α-helical domain can

bind the FERM domain to facilitate the masking of both domains. The

C-terminal end is the F-actin binding domain, also known as the

C-terminal ERM-association domain (C-ERMAD), which has the ability to

bind the FERM domain or F-actin. (B) The crystal structure of ERM proteins (reproduced from [3] and authorized by the publisher). (C) The inactive form of ERM proteins with C-ERMAD domain binding to and covering the FERM domain. (D) The active form of ERM proteins with the FERM domain released from the binding to the C-ERMAD domain.

2.2. Radixin Activation

While

performing its biological activities, ERM changes its conformation from

inactive to active. The two confirmations are inactive closed form and

active open form. The FERM domain of ERM proteins is shut in an inactive

state due to the interaction of the N-terminal end with the C-terminal

regions [2]. As shown in Figure 1C,

in the inactive closed conformation, the C-ERMAD domain binds and

covers both the F-actin and N-ERMAD (FERM domain), masking interaction

sites of the FERM domain and F domain, leading to the loss of their

binding ability to the membrane proteins, cytoskeletal protein, and

other adaptor proteins [5].

Further studies indicated that the central α-helix-rich domain and

linker regions also interact with F1 and F2 of the FERM domain,

contributing to the masking of the binding sites [6].

To

release the FERM domain from intermolecular binding, phosphorylation of

conserved residue, threonine (Thr), in the FERM domain is required. Thr

phosphorylation disrupts the binding between the FERM domain and the

C-ERMAD region, relieving the FERM domain from the intramolecular

association (Figure 1D).

The phosphorylation of radixin has been demonstrated to disrupt the

binding to the N-terminal domain to recover the binding ability of FERM

without affecting the F-actin binding site. Phosphorylation of ezrin and

moesin simultaneously unmasks both the F-actin and FERM binding sites.

Ezrin is activated through phosphorylation of Thr567 at the C-ERMAD

domain [7],

leading to attenuating the affinity of the FERM domain to the C-ERMAD

and reopening the binding sites of F-actin. The equivalent

phosphorylation sites of radixin and moesin are Thr564 and Thr558,

respectively [8].

However, phosphorylation of C-terminal Thr573 of radixin is required

for both F-actin binding and improves protein stability [9].

2.3. Kinases and Radixin Phosphorylation

Many cellular kinases can phosphorylate the residues in C-ERMAD domain (Table 1).

G-protein coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) phosphorylates ezrin on

Thr567, and is involved in membrane protrusion and motility in

epithelial cells [10] and in G protein-coupled receptor-dependent cytoskeletal reorganization [11].

GRK2 regulates cell migration during wound recovery in epithelial cell

monolayers, at least partly by phosphorylating radixin [12].

Nick interacting kinase (NIK)-induced phosphorylation of ezrin on

Thr567 is necessary for lamellipodium extension induced by growth

factors [13].

Lymphocyte-oriented-kinase (LOK) is a major ERM kinase in resting

lymphocytes, and phosphorylation of ezrin regulates the cytoskeletal

organization of lymphocytes [14]. Protein kinase C (PKC) phosphorylates ezrin to regulate osteosarcoma cell migration [15]. PKC-alpha has been shown to prefer ezrin as its target for phosphorylation [16], while PKC-theta prefers to phosphorylate moesin on Thr558 [17].

However, phosphorylation of ezrin by PKC-iota is essential for its

normal distribution, and may be involved in the differentiation of

intestinal epithelial cells [18].

More at link.

No comments:

Post a Comment