If this was truly possible for stroke it would be worthy of the Nobel Prize for Medicine. Because stroke survivors want 100% recovery not just progress! GET THERE!

12 Ways to Progress Any PT or OT Exercise, Activity, or Movement, Part 1

Editor's note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, 12 Ways to Progress Any PT or OT Exercise, Activity, or Movement, Part 1, presented by Andrea Salzman, MS, PT.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to identify six methods to progress any therapeutic activity as described in the webinar.

- After this course, participants will be able to compare and contrast two methods for altering feedback during patient care.

- After this course, participants will be able to compare and contrast two methods for incorporating dual-task processing into patient care and differentiate methods to incorporate part-task training and variability into patient care.

Introduction

Greetings, I am delighted to be with you today. I have a multitude of ideas to enhance our understanding and practice. In the following course, we will delve into six key concepts, promising six more to come in the subsequent segment.

A Lesson From the Past

- I recall my 1st clinical affiliation as a PT student. My clinical instructor ran the entire department sitting on a stool.

- Identical treatments for each person.

- A routine-driven approach with no deviation.

- Unending chair-based marching exercises and limited variation.

- Exercises were "cookbook" without clinical awareness.

- Exercises lacked functional relevance.

- Designed for the ease of the therapist, not the progression of the patient.

My professional journey spans over 50 years in physical therapy. A pivotal chapter in my early career was shaped by my first clinical affiliation in a skilled nursing facility. The department was nestled in a basement devoid of natural light. Despite the dim setting and low ceilings, the facility thrived with therapists dedicated to their work.

My mentor, the head of the department, left an indelible mark on me. Operating from a rolling stool, she orchestrated the entire department with remarkable efficiency, seldom rising from her mobile perch. Observing her distinctive approach, I couldn't help but reflect on the lessons I was absorbing, recognizing that perhaps the intended teachings differed from my interpretations.

The treatment paradigm I witnessed was consistent and, in my view, lacked the nuance of skilled care. Every patient, irrespective of their condition, received nearly identical interventions. It involved short arc quad sets, marching, overhead reaching, bicep curls, and minimal sit-to-stand maneuvers for those seated. Those in a standing position engaged in what affectionately became known as the "kitchen exercises," a routine featuring marching, hip abduction, hip extension, toe raises, heel raises, and squats. This regimented routine, marked by its lack of deviation, struck me as restrictive, especially given the diversity of patient needs. Despite time constraints, I believed a more skillful and individualized approach was possible and essential.

The incessant repetition, particularly the marching with cuff weights as the sole progression, left me questioning the efficacy. It became evident that many patients struggled with basic standing and mobility, yet the prescribed exercises remained seated or focused on rudimentary movements.

Before officially becoming a physical therapist, I was an occupational therapy wannabe. Seeking a marriage of skill and functionality, I drew inspiration from an occupational therapist within the department. This newfound insight reshaped my perspective, influencing my subsequent practice.

In retrospect, I recognized the convenience-centric approach employed—a disappointment at the time. Nevertheless, the lasting impact of that experience, now recounted decades later, underscores its significance in shaping my approach and fostering a commitment to patient-centric, functionally-driven care.

Fell's Methods of Progression

- A 2004 article in the Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy changed how I did therapy.

- Fell introduced 13 methods to complicate or simplify exercises, tasks, or activities.

- These methods have stood the test of time and continue to be relevant.

- They provide PTs/OTs with a structured approach for exercise progression.

- They offer therapists a clear decision-making pathway for enhancing outcomes.

(Fell, 2004)

I want to bring attention to a transformative article from the "Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy," published in 2004. While it might not be widely discussed, its impact on my practice has been profound, significantly influencing the manner in which I approach patient progression. This article serves as a foundational framework, guiding me to devise 12 (from the 13) distinct methods for advancing and tailoring interventions. These methods encompass a spectrum, allowing for adjustments to increase or decrease difficulty and to introduce varying levels of neurological challenge. It has become an invaluable scaffold in my clinical toolkit, shaping my approach to patient care and contributing to a more nuanced and individualized progression strategy. Figure 1 shows an illustration of the methods.

Figure 1. Illustration of 13 distinct methods for optimal performance and learning.

While I acknowledge there are technically 13 methods, I often consolidate amplitude with velocity, simplifying it to a more practical 12. Despite being rooted in a 2004 article, these methods have proven resilient over time, maintaining relevance nearly two decades later. They serve as a reliable touchstone, especially when faced with the challenge of progressing a patient's treatment. In those moments of uncertainty, these 12 methods provide a clear decision-making pathway, offering a structured approach to enhance therapeutic outcomes.

As the director of Aquatic Therapy University (ATU), a commitment to evidence-based care is paramount. Our instructors diligently incorporate literature from the field, particularly focusing on aquatic therapy. Notably, a significant portion of aquatic therapy literature lacks specific guidance on progressing care in the water. Many studies outline the activities conducted, such as therapeutic exercises, stretching, and aerobic exercises, often without detailing the progression methodology. This gap in instruction compelled me to emphasize the importance of incorporating proven methods, such as the 12 I've outlined, to drive effective and tailored progression, even when the core activity remains constant.

Method 1: Task Attention (Dual-Task Processing)

- Progress an activity by reducing the ability to attend to a task.

- This technique is often called "dual-task processing" in therapy.

- Reducing a patient’s attention to a task can increase difficulty without changing the physical task.

- Older adults often have trouble with dual-task processing.

(Muir-Hunter & Wittwer, 2016)

Let's delve into the first method, task attention or, more colloquially, dual-task processing. This involves challenging patients to perform a physical task while engaging in a cognitive activity. While the term "dual-task" may imply the ability to truly multitask, scientific research suggests that our brains excel at rapidly switching between two activities rather than performing them simultaneously.

Allow me to illustrate with a personal anecdote. My husband, a former A10 fighter pilot, often seemed like he could seamlessly manage multiple tasks while flying. However, the reality is that he adeptly shifted his focus between internal cockpit details and scanning the horizon. The brain's capacity to switch quickly between tasks rather than execute them concurrently is a crucial distinction.

Now, as therapists, incorporating dual-task processing into our sessions can yield remarkable results. It introduces a cognitive component to physical tasks, and studies indicate that this approach can enhance therapeutic outcomes. However, a key piece of advice for fellow therapists is to avoid overwhelming patients with too many changes. As we say in the South, "suck the marrow from the bone" – find a foundational activity that works well and progressively build upon it. This gradual approach respects the learning curve: understanding, executing, refining, and ultimately enjoying the activity.

Consider the analogy of an aerobics class. If an instructor constantly changes routines, participants may struggle to keep up and find the experience less enjoyable. Similarly, maintaining a stable base activity and introducing layers, such as dual-task challenges, can be highly effective with our patients.

In the context of older patients, it's evident that adding a cognitive element to a physical task can be seamlessly integrated. Picture a scenario where you use a gait belt to assist an elderly patient during a walk. Simply asking about their granddaughter, a recent wedding, or spouse can introduce a cognitive load. You observe how they momentarily stop, answer your question, and then resume the physical activity. This straightforward method exemplifies the power of dual-task processing, turning routine activities into valuable therapeutic moments.

- Dual-task training has been associated with reducing future fall risk. This association is stronger than that for single-task conditions.

- The combination of cognitive stimulation and physical exercise training can reduce the progression of cognitive decline and improve physical fitness and quality of life.

(Jardim et al., 2021)

Now, let's explore the profound benefits of dual-task training, particularly its association with a substantial reduction in future fall risk. The connection between cognitive engagement and physical tasks in dual-task training is more robust than focusing solely on the physical aspect. Therapists can achieve a two-fold impact by integrating cognitive stimulation with physical activities, addressing cognitive decline and the desired physical outcomes.

This approach offers a unique advantage by promoting physical well-being and contributing significantly to cognitive health. The synergy between cognitive and physical engagement creates a more comprehensive therapeutic experience, essentially providing a two-for-one benefit. As therapists, this dual-task strategy becomes a powerful tool in our arsenal to enhance overall patient outcomes and quality of life.

Sample Interaction Scenario #1: Adding Cognition to an Intervention

- Location: Family conference at a hospital, rehab center, or skilled nursing

- Basic interaction: The patient and family meet with a social worker, therapist, and nursing representative. The health care team asks simple “yes/no” queries of the patient.

- Adding a Cognitive Overlay:

Conferences are an ideal time to tease out how much the patient

understands about their care. If the meeting is geared around a

discharge plan, the patient should be asked direct, open-ended

questions, such as:

- At home, how many steps does it take you to get inside?

- Where is the bathroom that you plan to use?

- Do you think you are ready for discharge?

- What scares you the most about going home?

(Salzman, 2019)

How can we integrate cognition into our practice through specific scenarios many of you may encounter? Picture yourself in a family conference within a hospital, rehab center, or skilled nursing facility. The common setting involves everyone sitting at a table to discuss the ongoing situation and the discharge plan. In typical interactions, the therapist might briefly contribute, asking yes or no questions often directed more at the family than the patient. However, to transform this into a dual-task processing moment, conferences provide an excellent opportunity to assess the patient's understanding of their situation.

During a discharge-focused meeting, direct open-ended questions to the patient become crucial. Instead of merely inquiring about their readiness for discharge, dig deeper. Ask questions like, "At home, how many steps do you take to get inside?" Maintain eye contact with the patient and involve them directly in the conversation. Explore their perspective on the bathroom location at home and inquire about any concerns they might have regarding going home. While time constraints are acknowledged, this intentional interaction has the potential to turn into a therapeutic moment for the patient.

Sample Interaction Scenario #2: Adding Cognition to an Intervention

- Location: During wheelchair transport to the therapy department.

- Basic interaction: The patient is brought to therapy or returned to the room/car etc.

- Adding a Cognitive Overlay: Transport time is the perfect opportunity for pathfinding exercises. When the elevator doors open and the patient finds himself back on “home turf”, it’s a great opportunity to ask

- “If you don’t mind, direct me back to your room. Should I turn here or here?” (Wait for direction. If the direction is wrong, stop and prompt.)

(Salzman, 2019)

Consider another scenario where you may not directly interact with the patient, but someone else is escorting them to the department. At a St. Paul, Minnesota hospital, we implemented a practice to enhance cognitive engagement during these moments. As the transport staff navigated through the hospital—riding elevators, making turns, and winding through hallways—they incorporated questions into their dialogue.

For instance, upon opening the elevator doors, they might inquire, "Do you know where your room is?" or "Can you point to your room for me?" Progressing through the halls, questions like, "Which way do you think therapy is? Left or right?" helped stimulate the patient's cognitive processes. While this doesn't fall under billable skilled care, it effectively infuses cognition into the patient's experience. Encouraging the patient to direct the escort back to their room and asking, "Should I turn here or here?" adds an extra layer of engagement, providing a cognitive challenge during the journey.

Sample Interaction Scenario #3: Adding Cognition to an Intervention

- Location: During transfer training from one surface to another

- Basic interaction: The patient is transferred by 1 or more individuals from one surface to another

- Adding

a Cognitive Overlay: Transfers happen dozens of times each day.

Unfortunately, transfers are often done in a manner that is foreign to

the natural instincts of the patient, meaning that a greater load of the

work is borne by the family or staff. To introduce a cognitive

challenge, ask the patient to problem-solve the transfer.

- Where do you want me to stand?

- What will make getting up easier on you?”

- Wait for an answer, but prompt with ideas such as:

- should you scoot to the edge of the seat,

- lean weight forward,

- use rocking for momentum?

(Salzman, 2019)

Consider another scenario where you can integrate cognition into your therapy sessions, specifically during transfer training. As therapists, we often observe individuals moving from one surface to another, be it from a chair to a wheelchair, from the wheelchair to a mat, or from a sitting position to sand. In traditional practices, this transfer is a routine, straightforward activity. However, I've noticed that the environment greatly influences the perceived difficulty of transfers. At home, individuals often have a system—utilizing a specific side of the bed, leveraging a bedside table, or cruising furniture—that suits their unique needs. However, these established patterns are disrupted when transitioning to settings like skilled nursing.

To enhance cognitive engagement during transfer training, involve the patient in problem-solving. Instead of initiating the process and guiding them step by step, ask open-ended questions that prompt them to think through the transfer. Questions like, "Where do you want me to stand? Where do you feel safest if I'm standing there?" empower them to choose the most comfortable and effective approach. While safety remains a priority, giving individuals the space to solve the problem on their terms often results in a smoother transfer.

You can encourage cognitive participation by asking, "What will make getting up easier? Do you want to hold onto something or prefer scooting forward?" Allow them the opportunity to provide input and wait for their response. Provide prompts to guide them through the steps, ensuring they actively contribute to the decision-making process. For instance, inquire, "Does it help to lean forward when you get up?" Using relatable terms, such as "butt power," can make the guidance more memorable and reinforce the idea that they have the capacity to determine the best approach for their unique situation. This shift from directive to collaborative problem-solving adds a cognitive dimension to the transfer training, promoting a sense of autonomy and engagement.

Sample Interaction Scenario #4: Adding Cognition to an Intervention

- Location: During gait training sessions

- Basic interaction: The patient walks from point A to point B during gait training

- Cognitive

enhancement: Whether it’s performed in the patient’s room in a

hospital, at home, or in the clinic, gait time should be cognitive time.

- Have the patient ambulate while counting backward from 30… by three.

- Or verbally describe the drive to work (“After I turn right out of my driveway, I go through the neighborhood until I arrive at the roundabout.”)

- Or ask the patient to describe the best way to cook a turkey.

- Or do alphabet math.

(Salzman, 2019)

Next, we will look at incorporating cognitive elements during gait training. In the past, the focus was often on covering a certain distance swiftly, but now we understand the importance of adding nuance to this process. Instead of merely moving from point A to point B, consider introducing cognitive engagement unless it compromises safety.

For instance, you could integrate counting backward into the gait training session. Rather than setting a predetermined endpoint, have the individual count backward as they walk. This keeps them engaged and serves as a dual-task, enhancing cognitive and physical coordination. Another approach involves having them verbally describe their route to a familiar destination, such as church or work. This prompts them to visualize the path, resulting in shifts in gaze and a change in walking dynamics. While their walking speed might decrease, the therapeutic benefits of cognitive engagement make it a valuable addition to the session.

Moreover, tapping into personal experiences can be beneficial. Ask questions about their past, like their favorite dance moves. In aquatic therapy, incorporating past activities, such as line dancing, can be both enjoyable and therapeutic. Additionally, inquire about their favorite ways to cook a turkey or share personal anecdotes to make the session more relatable.

I want to share one standout moment. A university-level college female basketball player entered the pool with a profound aversion to aquatic therapy. To her, the pool was synonymous with injury and setbacks—where one ended up when things weren't right with the body. Undeterred, I aimed to show her the performance-enhancing potential of water-based exercises.

Equipping her with a couple of floatations and securing her in place with bungees, we embarked on an unconventional approach: cross-country skiing in the pool. To her surprise, the activity felt remarkably easy. At this juncture, a conventional therapist might have opted for the usual route, increasing resistance and difficulty through drag-inducing tools. However, I took a different path.

Instead of intensifying the physical challenge, I introduced an element of cognitive engagement—alphabet math. Starting with a simple question like, "What is A plus one?" initiated a mental exercise. As she seamlessly responded, navigating through the alphabet and performing calculations, her cross-country skiing performance took a hit. Despite no increase in physical exertion, the cognitive challenge disrupted her usual patterns, making the familiar activity unexpectedly demanding.

Caught off guard by the combination of mental and physical demands, she inquired, "What witchcraft is this?" The seemingly straightforward task of cross-country skiing became a cognitive puzzle, requiring her to divert attention from physical motion to mental calculations. It was a moment of revelation, demonstrating the intricate interplay between physical and cognitive elements in therapy. This unexpected twist transformed a routine exercise into a cherished and enlightening experience.

In conclusion, gait training can be transformed into a cognitive engagement opportunity, offering a two-fold benefit—physical and cognitive—without entirely new interventions.

Clinical Reflection

- Therapists like you who can read a text-dense PowerPoint slide while listening to me talk are demonstrating what skill?

- Dual-task processing

- Here are a few more ways to add cognitive challenges to your treatments

- The Chopped Challenge

- The Dollar Store Challenge

In this moment, I invite you to pause and consider the role of a therapist like yourself—capable of deciphering a text-dense PowerPoint slide while actively engaging in conversation or demonstrating various skills. The challenge lies in absorbing the written information and integrating it seamlessly with other tasks. I intentionally inundated the presentation with extensive text, envisioning it as a future handout for your reference. This dual demand—listening to my words, reading the content, and possibly demonstrating specific skills—mirrors a concept known as dual-task processing.

It's a cognitive juggling act akin to the challenge posed when presenting information to a jury. Inundating an audience with reading material while expecting them to focus on your spoken words is a delicate balance. Yet, this is precisely what you're navigating now—simultaneously absorbing information, comprehending the spoken words, and potentially engaging in physical or mental tasks. It's a testament to your capacity for dual-task processing, highlighting the intricate nature of the therapeutic skills you bring.

Now, let's delve into a couple more engaging methods to infuse cognitive challenges into your treatment repertoire. First up is the "Chopped Challenge." If you're a fan of cooking or familiar with the Food Network Channel, you might have encountered the show "Chopped." In this culinary competition, chefs are presented with a basket of eclectic and unusual ingredients—lemongrass, jelly beans, fruit loops, and a steak. Their task? Create an appetizer, a main course, and a dessert, integrating these disparate elements seamlessly into each dish.

Drawing inspiration from this concept, I've incorporated my version of the Chopped Challenge into daily patient interactions. The idea is to pair two seemingly unrelated things I've never combined before and transform them into something novel. This can be a collaborative effort with the patient, fostering problem-solving skills and creativity, or a personal experiment during breaks between patient sessions. The goal is to spark curiosity and explore the unexpected synergies of combining diverse elements. It's not just about the end result; it's about the process of navigating through uncharted territories, pushing boundaries, and, in the end, enriching your skills as a clinician.

Here is another memorable moment from my career as a therapist. I was covering a 13-week maternity leave for a colleague, and during this period, I found myself in the therapy pool. Having spent decades in aquatic therapy, it was starting to feel like routine – the same old exercises and strategies. That's when the universe threw me a curveball in the form of bath blankets, those large absorbent sheets familiar to anyone working in skilled nursing.

Exiting the pool, we would wrap ourselves in these bath blankets, but the problem was they'd end up soggy and undesirable for reuse. After a few weeks, the facility decided to cut me off, allowing me only two bath blankets. Determined to turn this limitation into an opportunity, I proposed a challenge – what if I could creatively utilize a bath blanket in the pool?

From that moment forward, I embarked on a journey of exploration, developing what I now fondly call "Salzman Blanket Drills." Over those 13 weeks, I concocted around 60 distinct exercises using the bath blanket, with approximately 40 proving remarkably effective. The routine became a staple in the pool sessions, adding a new layer of engagement and challenge.

It's worth noting that I've since transitioned to using chiffon scarves for these drills, as they dry more quickly. The key takeaway is the daily commitment to challenging myself, pushing the boundaries of conventional tools, and fostering creativity. What started as a personal experiment in the therapy pool has become a shared experience in conferences, private trainings, and outpatient centers.

The fascinating part of this journey is witnessing different individuals with unique backgrounds consistently conjuring new ideas. I encourage them to use the same tools and come up with something fresh; without fail, they deliver. It's a testament to the magic that happens when diverse perspectives converge, and I can't help but admit that, occasionally, I borrow – or rather, "steal" – these fantastic ideas. After all, there's no patent on inspiration in the world of creativity, and innovation is meant to be shared.

Let me introduce you to another exciting approach that has added a dash of creativity to my therapy sessions – the Dollar Store Challenge. This challenge is a delightful exercise where I encourage therapists to stroll through their local Dollar Store without any specific item in mind. The goal is to explore the store and contemplate how seemingly ordinary items, like a level, could be transformed into therapeutic tools. For example, I began incorporating the level into sessions, challenging individuals to keep the bubble in the middle as they stood. The simplicity of the activity, combined with its affordability, made it an instant hit.

The essence of the Dollar Store Challenge lies in the spontaneity and playfulness it introduces to therapy. It's about embracing the unexpected and finding therapeutic potential in ordinary items. By encouraging therapists to explore these stores, I hope to ignite curiosity and playfulness in their practice. The therapeutic journey, after all, is enhanced when we infuse it with a touch of creativity within the bounds of safety.

Now, let's move on to technique number two.

Method 2: Feedback

- Gradually reduce the amount of feedback provided

- Strong verbal encouragement is commonly used (think of your coach yelling at you as an athlete) as feedback, but there are many more options

- Feedback can be verbal, gestural, visual, modeling, or physical

- Reducing the amount of feedback is a simple way to progress

- How does this look in practice?

- Let’s look at types of “prompts”

Technique number two is a method that amplifies the impact of your therapy sessions by using feedback. Contrary to the common notion of reducing feedback to increase difficulty, this approach suggests that increasing feedback can intensify the challenge. Now, let me break down what this entails.

Recall those memorable moments when a coach or mentor yelled at you. While we certainly won't be screaming at our patients, it's essential to recognize the power of verbal cues. Coaches often use loud commands to elicit a heightened response, increasing muscle engagement and enhancing performance. Though we won't be employing the same vocal intensity, understanding the influence of verbal cues can significantly impact therapeutic outcomes.

However, verbal cues are just one facet of effective feedback. Gestures play a crucial role in conveying information and guiding patients through exercises. A well-timed gesture can communicate instructions, encouragement, or corrections more effectively than words alone.

Imagine a scenario where a simple hand motion communicates proper form during an exercise or a nod of approval reinforces a positive movement. This multi-sensory approach to feedback, combining verbal and non-verbal elements, creates a dynamic and engaging therapeutic environment.

As we explore the nuances of feedback, consider how this multifaceted approach can enhance your interactions with patients, making each session more impactful and memorable. Now, let's delve deeper into this technique.

One engaging technique we've implemented in aquatic therapy sessions is "dolphin drills." This method involves physical activity and incorporates various forms of feedback to enhance the experience. Imagine working with a child in the pool, introducing them to being a dolphin. The first task is to go up and down in the water, mimicking the characteristic movement of dolphins.

To initiate this, I whistle and signal a specific gesture the child had previously chosen and associated with this action. They respond by going up and down, facing me, anticipating the next instructions.

The fun part comes when we introduce additional dolphin behaviors. For instance, dolphins are known for their playful spins. I use a different gesture to convey this action, and the child interprets it to spin around in the water. Another playful behavior is their chattering, which another unique gesture prompts. The challenge lies in the child's ability to recall their chosen gestures and mentally process them without verbal cues.

Taking it further, we incorporate "build a move" scenarios. I might instruct the child to combine two gestures: going up and down and then chattering. This adds complexity and encourages cognitive engagement as they seamlessly integrate the gestures into a coordinated sequence.

This approach integrates verbal, gestural, and visual feedback, fostering creativity, cognitive processing, and physical activity. Whether modeling a behavior, providing visual cues like posted instructions, or offering physical feedback aids, this multifaceted approach transforms therapy into an interactive and enjoyable experience.

Modeling is a technique that incorporates various learning styles and provides a dynamic approach to therapy. When considering how students learn, a study found that they grasp information through seeing, hearing, doing, and engaging in challenges. This principle can be applied effectively in therapy to enhance the learning experience.

Starting with seeing, clients observe and learn by watching. The next layer involves verbal instruction, where I guide them through the task or exercise. Moving to the doing phase increases their understanding, and incorporating challenges further enhances learning. Challenges don't necessarily have to be competitive but should stimulate engagement and motivation. For instance, timing the task can transform it into an exciting challenge.

Taking it a step further, I introduce the concept of "teach the teacher." Clients are encouraged to teach the skill or exercise back to me. This requires them to articulate the steps and process, reinforcing their understanding. To elevate the challenge, I introduce "correct the teacher." In this scenario, I intentionally perform the task incorrectly after the initial correct demonstration. The client then identifies and corrects the error, showcasing a deep comprehension of the task.

This multifaceted approach provides a comprehensive and engaging learning environment, incorporating seeing, hearing, doing, teaching, and correcting. It aligns with the principle that active participation, challenges, and the ability to teach others significantly contribute to the learning process.

- An effective way to help learn new skills is to provide prompts that are eventually faded

- These are called “response prompts”

- Prompts are additional stimuli provided DURING the task/behavior to evoke correct responses

- Prompts are used to facilitate a correct response

Prompting is a crucial aspect of facilitating task performance, involving using response prompts to guide individuals toward correct and effective execution. These prompts, diverse in nature, cater to the unique needs of individuals and are categorized based on the assistance they provide.

Physical prompting entails hands-on support, making it suitable for those who require direct assistance. The fading strategy involves gradually reducing physical guidance and promoting increased independence in task completion.

Verbal prompting employs spoken cues or instructions to guide individuals through tasks, catering to those responsive to auditory cues. Fading in this context involves decreasing reliance on verbal prompts and encouraging self-initiated actions.

Visual prompting relies on visual cues or aids, benefiting visual learners or those who comprehend better with visual support. The fading process here aims to reduce dependence on visual prompts, fostering the internalization of cues.

Gestural prompting uses non-verbal cues or gestures to signal desired actions, which is particularly effective for individuals responsive to non-verbal communication. Fading gestural prompts involves reducing dependence and encouraging individuals to internalize cues.

Model prompting entails demonstrating desired behaviors for individuals to imitate, which is especially beneficial for observational learning tasks. The fading approach includes gradually decreasing modeling frequency, facilitating independent execution.

The overarching objective of employing response prompts is to guide individuals toward correct task performance, emphasizing quality over sheer repetition. As individuals gain proficiency, the systematic fading of prompts becomes pivotal, promoting increased independence and skill acquisition. This approach aligns with the principle that effective practice involves correctness and precision.

Response Prompts

- Most-to-least prompting

- Least-to-most prompting

- Constant time delay

- Progressive/gradual time delay

- Knowledge of results

- Knowledge of performance

Here are some fabulous prompts that you can use. Let's go over these.

Most to Least Prompting

- Most

to least prompting is defined as eliminating the prompt over time by

starting with the highest level of prompt that enables the individual to

respond correctly.

- Think of hand-over-hand PNF.

- Think of handwriting instruction.

- Think of language acquisition.

- Effective in teaching communication, self-care, and leisure skills (among other things) to individuals from various age and disability groups.

(Kutlu, 2023)

Most-to-least prompting is a strategic approach where prompts are gradually phased out over time. It involves initiating assistance at the highest level necessary for the individual to respond correctly. This method is particularly beneficial in various contexts, such as proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) exercises, handwriting instruction, and language acquisition.

In PNF exercises, a therapist might use hand-over-hand guidance to ensure the correct execution of movement patterns. Similarly, in handwriting instruction, providing initial support by guiding the hand helps prevent the reinforcement of incorrect patterns. Language acquisition relies heavily on most-to-least prompting, ensuring correct pronunciation from the beginning to establish accurate engrams or neural patterns.

For instance, in language learning, the method involves correcting pronunciation immediately to avoid ingraining incorrect speech habits. A meta-analysis illustrates that most-to-least prompting has proven highly effective in teaching various skills, including communication, self-care, and leisure activities, across diverse age groups and populations. The gradual reduction of prompts aligns with the individual's progression, fostering independence and skill acquisition.

Least to Most Prompting

- Least to Most Prompting uses the least restrictive or invasive prompt level in order for the patient to see success.

- Most effective for patients who demonstrate the pre-requisite skills necessary to complete a task but are not performing the task.

- The invasiveness of the prompting is increased if the patient responds incorrectly.

(Vascelli et al., 2021)

Least-to-most prompting is an approach that initially focuses on using the least restrictive or invasive prompts to allow the patient to experience success. This method is particularly beneficial when individuals already possess the basic components of a task but are working on integrating and refining those components for more seamless and natural execution.

Unlike most-to-least prompting, where you start with the highest level of assistance, the least-to-most prompting begins with minimal intrusiveness. The individual is given the opportunity to demonstrate their understanding and ability with the task's fundamental elements. As the therapist observes, if it becomes evident that the patient is struggling or performing incorrectly, the level of prompting can be increased incrementally.

This approach aligns with the idea that individuals should be provided with the least assistance required to achieve success, promoting a sense of autonomy and skill development. Least-to-most prompting recognizes the importance of balancing support and challenge to facilitate learning and task mastery.

Constant Time vs. Progressive Time Delay Prompting

- Constant time delay prompting is a teaching strategy that can help patients acquire new skills or tasks.

- It involves providing a prompt, or a hint, to help the learner respond correctly after a certain amount of time has passed.

- The prompt is given at the same time as the instruction when the learner is first learning the skill (0-second delay).

- The prompt is gradually delayed as the learner becomes more proficient (3 or 4-second delay).

- Another option is Progressive Time Delay, where the delay grows longer.

(Chazin & Ledford, 2021)

Time prompting strategies, such as constant and progressive time delays, are particularly valuable when working with individuals with neurological delays or learning difficulties. These techniques ensure that individuals are given adequate time to process instructions and respond appropriately, enhancing their ability to perform activities or tasks.

Constant time prompting involves providing a prompt or hints to assist the individual in responding correctly after a specific, predetermined amount of time has passed. For example, if you instruct someone to "Throw me the ball," you wait for a set duration, such as four seconds, before offering assistance. This method is particularly effective during initial skill acquisition when prompts are given simultaneously with instructions and gradually delayed to encourage independent performance.

In contrast, progressive time delay gradually increases the duration of time before providing prompts. For instance, you might start with a four-second delay, then progress to eight seconds, and so on. This approach allows individuals to gradually become more independent in their responses as they gain confidence and proficiency in the task.

Both constant and progressive time delay prompting techniques aim to foster independence and skill development by gradually reducing the need for external support and encouraging individuals to rely on their own problem-solving abilities and knowledge.

Knowledge of Results vs. Knowledge of Performance

- Knowledge of results and knowledge of performance are two types of feedback.

- Knowledge of results focuses on the outcome or the end of the performance (score, time, or position).

- Knowledge of performance focuses on the quality and pattern of the movement (technique, accuracy, or speed).

- Knowledge of performance is often more important than knowledge of results for learning new skills.

(Oppici et al., 2021)

The distinction between knowledge of results and performance is crucial in providing effective feedback during skill development. Imagine working with a basketball player aiming to eliminate hip pain during layups. In this scenario, if you assess whether they successfully make the basket or perform the layup without experiencing pain, you are offering knowledge of the results.

Knowledge of results concentrates on the overall outcome of the action, such as successfully making a basket or performing the layup without pain. It involves evaluating the final score or whether the desired outcome was achieved.

On the other hand, knowledge of performance delves into the intricacies of the movement itself, emphasizing the quality, pattern, and technique employed. This type of feedback assesses factors like accuracy, proper use of the backboard, and movement speed. Studies suggest that especially when learning a new skill, knowledge of performance holds greater significance than knowledge of results. Focusing on the specific elements of the movement allows for a more comprehensive understanding and improvement of the technique.

In summary, understanding the difference between knowledge of results and knowledge of performance enables you to provide more targeted and effective feedback during skill acquisition, emphasizing the details of the movement rather than just the end result.

Clinical Reflection

- Ask: What are the steps from skill acquisition to mastery stage?

- Remember: The learning curve on many therapy activities can be steep.

- Sometimes, therapists think a skill is “old hat” because it is “old hat” to the therapist. This can lead to a too fast progression.

Reflecting on the steps from skill acquisition to mastery is crucial in guiding patients through the learning process. The learning curve for many therapy activities can be steep, requiring careful consideration of the progression. It's important to recognize that what may seem like a simple skill to a therapist may not be as straightforward for the patient.

When introducing a new skill, it's easy to forget that the patient lacks the therapist's knowledge. A therapist may assume that a skill is old hat because of familiarity, but the patient might be entirely unfamiliar. This discrepancy in knowledge can lead to misunderstandings and frustration.

A key example is teaching a spouse to assist with back pain by providing traction. While the therapist sees it as a simple maneuver, the spouse may find it challenging, leading to potential discomfort or anxiety. It's essential to be mindful of these differences in knowledge and not move at a pace comfortable for the therapist but at a pace suitable for the patient's understanding and comfort.

Avoiding assumptions about the patient's familiarity with a skill and adjusting the pace of instruction can significantly impact the patient's ability to acquire and master the skill. It's a reminder that effective teaching involves patience, clear communication, and an awareness of the individual's learning needs.

Method 3: Assistance Given

- Change the Level of Assistance the Therapist Provides.

- A gradual withdrawal of assistance will help exercise progression.

- There is a common tendency for therapists to provide excessive assistance.

- We do too many tasks for patients, hindering skill development.

- Any assistance should enable patients to surpass current limitations.

- There is a right balance between facilitation and independence.

(Lloyd et al., 2009; Bergen, 2016)

The third method for progression is evaluating the amount of physical assistance provided to the patient. Physical assistance, or how much the therapist intervenes with hands-on guidance, is a critical aspect of therapy. Often, therapists may provide excessive help due to fear of potential consequences or even out of convenience.

Due to its reduced impact, the pool environment allows therapists to let patients attempt activities that might be riskier on land. However, the tendency to offer too much assistance is still prevalent. In gait training, for instance, therapists may intervene quickly if they sense a patient's instability, preventing the individual from experiencing and correcting the imbalance independently.

It's essential to recognize that providing assistance should be strategic. The goal is to enable patients to surpass their current limitations gradually. A helpful guideline is encouraging patients to succeed around 51% of the time during a session. This balanced approach allows individuals to succeed and acknowledges the necessary challenges for skill development.

Finding the right balance between facilitation and independence is crucial. Hitting this balance ensures patients have opportunities to learn and improve while still receiving necessary support. It's a delicate equilibrium that, when achieved, promotes effective skill development without hindering progress.

- One progression method is to reduce the physical assistance provided.

- Dependent (D): The patient is unable to participate actively, and the therapist or caregiver must provide full assistance to complete the activity.

- Maximal Assistance (Max A): The patient requires substantial physical support to perform the task. They are actively involved but need help with most aspects.

- Moderate Assistance (Mod A): The patient needs moderate physical assistance to complete the activity or exercise.

- Minimal Assistance (Min A): The patient requires minimal physical support or supervision. They can perform most of the task independently.

- Independent (I): The patient can perform the activity or exercise without any assistance or supervision.

The traditional categories of assistance levels, ranging from complete dependence to full independence, are common concepts in therapy. However, it's crucial to recognize the relativity of these terms. Each individual's situation is unique, and circumstances can create a nuanced understanding of their level of dependence or independence.

Consider the example of a woman getting out of a different side of the bed than at home. Initially, it might appear that she is completely dependent, especially if she needs assistance getting out of bed or navigating her new surroundings. However, this apparent dependence may not accurately reflect her capabilities and potential for independence.

Therefore, therapists should approach these categories flexibly and consider the specific context and individual factors influencing a person's level of assistance needs. The goal is to tailor the assistance provided to each person's unique circumstances, recognizing that a person's capabilities and independence can evolve over time.

- In the geriatric population, falls can claim top billing as the leading cause of injury-related death and disability. Following a hip fracture, frequent and injurious falls are common; one study observed an elevated fall risk in 92% of participants in the year following hip surgery.

- In 2014, almost 30% of the over-65 population fell, with a third of those who fell needing medical treatment or some restriction from activity to recover. In a single year, falls were blamed for the death of an estimated 33,000. And that was in the USA alone.

(Lloyd et al., 2009; Bergen, 2016)

In the geriatric population, falls emerge as a predominant contributor to injury-related fatalities and disabilities. Following hip fractures, individuals often experience frequent and injurious falls. A study revealed a staggering 92% elevated fall risk in people during the year following hip surgery. Medicare's findings, dating back to 2016, reported that almost 30% of individuals over 65 experienced falls within the studied year. Notably, a third of these cases necessitated some form of treatment. Furthermore, falls were implicated in approximately 33% of deaths in the US during a single year. It's important to acknowledge that falls could be higher, as many individuals may not report these incidents. During my tenure in home health, it was common for people to downplay the frequency of falls, considering them a normal part of life, despite their evident risks and consequences.

Clinical Reflection

- When is assistance more than assistance?

- What is the “Power of Human Touch”?

- When I remove physical contact, what happens?

- What role is the “physical assistance” providing.

- Does “less physical assistance” always lead to progress?

(Field, 2010)

Let's contemplate the significance of assistance transcending mere physical aid. While I advocate for the necessity of providing and eventually withdrawing assistance for progress, there's an undeniable magic in the power of touch. Dr. Tiffany Fields conducted groundbreaking studies, particularly examining the impact of touch on babies' well-being. One study that captivated me focused on seniors receiving and giving massages. The findings revealed substantial improvement in back pain for both groups. However, those who engaged in massaging babies experienced even greater relief. The reasons behind this phenomenon are multifaceted, encompassing feelings of being needed and, significantly, the therapeutic effects of touch. When contemplating reducing physical assistance, it's essential to recognize that less touch doesn't always equate to progress. In some instances, touch remains a crucial element for achieving advancements in therapy.

- Importance of human touch in therapy:

- There was no difference in the effectiveness when it was provided by a familiar person versus by a health professional.

- The more frequently the touch occurred, the greater the positive health benefits.

- Shockingly, the session duration did not matter.

(Packheiser et al., 2023)

The 2023 study conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis, delving into various physical and mental health benefits of touch. The findings were quite intriguing. Firstly, the study emphasized that the source of touch didn't significantly matter – whether it was initiated by a family member or a healthcare professional, the key was that it constituted positive touch. Secondly, the frequency of touch played a crucial role, with more frequent touch correlating with greater positive health benefits. Due to safety and the unique sensory experience of being in the water, the pool setting naturally encourages more frequent touch. Remarkably, the study revealed that the duration of touch didn't necessarily matter; even brief, incidental moments of touch could yield positive mental and physical benefits.

- Physical benefits

- Touch activates orbitofrontal cortex and caudate cortex

- Touch decreases HR, BP, and cortisol

- Touch enhances immune function, including increasing natural killer cells

Touch triggers the activation of the orbitofrontal cortex and the caudate cortex. The orbitofrontal cortex, located behind the eye orbits, is associated with decision-making, problem-solving, and reward processing – functions often implicated in addiction. The caudate cortex, part of the basal ganglia, is responsible for motor planning and facilitating movement. Positive touch activates these regions, producing positive emotions and a sense of reward. Conversely, negative touch, such as frightening or threatening contact, triggers a withdrawal response or a desire to flee.

The physical benefits of touch are substantial. Positive touch alters serotonin levels in the brain, reduces heart rate, lowers blood pressure, and decreases cortisol levels. Moreover, it enhances the immune system by boosting T and killer cells, contributing to overall immune function. It's important to recognize that completely eliminating physical touch, assuming someone no longer needs it, might not always be advisable.

Method 4: Supportive Device

- Reduce or eliminate dependence on walkers, canes, etc.

- Walkers are simultaneously good and evil.

- They alter the patient’s natural balance and ambulation skills.

- There is a war between utter safety and skill.

- Moving from a walker to quad cane to single point cane requires motor learning. and practicing with the affected system.

- Therapists must balance independence with safety in device withdrawal.

I've written extensively about my somewhat controversial view on walkers, often referring to them as a necessary aid and a potential hindrance. The debate between nursing staff and therapy staff in skilled nursing settings often revolves around the perceived safety of walkers versus the encouragement of patients to regain their independence in walking.

In my perspective, walkers can disrupt a patient's natural balance and ambulation skills, creating a conflict between safety and skill development. While walkers are often seen as a secure option, they might inhibit the progression of walking abilities. Some argue for using walkers as a safety measure, especially when patients are not deemed safe with less supportive devices like canes or quad canes. However, the question arises: how does relying on a walker affect a patient's ability to regain independent mobility? It's a balance between safety and fostering skill development in walking.

- One progression method is to reduce the use of supportive devices.

- Crutches

- Walkers with wheels

- Standard walker

- Hemi cane

- Quad cane

- Single end cane

(Goher & Fadlallah, 2020)

Consider the scenario where we aim to progress a patient beyond using a walker, perhaps transitioning them to crutches or another less supportive device. Examining the impact of introducing a walker into the rehabilitation process is important.

- Canes, Crutches, and Walkers, oh my!

- Crutches – Require a lot of UE strength and stability.

- Canes – Offer maneuverability and ease of transport. Least stable of all assistive devices. Cannot “stand on its own” (unless it is a SBQC/LBQC/HemiCane). Requires UE strength and independent stability.

- Walkers - Provide a large base of support. Encourage a wide base of support. Difficult to turn. Difficult to lift.

- 2-Wheel Rolling walker – More functional and easier to use but can encourage dangerous forward propulsion and an even wider base of support.

- 4-Wheel Rolling Walker (Rollator) – Good for higher-functioning individuals who do not need to fully off-load a lower limb and who need rest breaks for cardiopulmonary endurance reasons. Least stable.

(Sehgal et al., 2021)

Consider the distinct characteristics of various walking aids: crutches demand substantial upper extremity strength and stability, canes are highly portable but less stable, and walkers offer a large support base yet pose challenges in maneuverability and lifting. The choice of walking aid depends on individual needs and abilities. It's crucial to recognize that each device has its advantages and limitations.

Regarding walkers, they provide a broad base of support but can be challenging to turn and lift. Some individuals resort to inefficient techniques, such as propelling the walker forward and leaning excessively while walking. There's a prevalent misconception that equipping a walker with only rear wheels enhances functionality or opting for four-wheeled walkers with seating features is a comprehensive solution. However, research indicates that traditional non-wheeled frame walkers may impede mobility in older patients, leading to shorter walking distances and increased energy expenditure compared to those using wheel walkers.

The energy inefficiency arises from a problematic adaptation – users tend to shift their center of mass forward onto their hands, adopting a stance resembling a modified quadruped position. This alteration in balanced reactions could hinder the development of more effective walking patterns, emphasizing the need for thoughtful consideration in prescribing walking aids.

- Walkers with Wheels versus Walkers without Wheels….. Which is better?

- Older patients walking with a non-wheeled frame had reduced mobility, resulting in shorter distances traveled and more energy use compared with patients using wheeled walkers.

- No comparative evidence on hospital admissions, severity of falls, and health-related quality of life for the wheeled and fixed walkers was found.

(Li & Farrah, 2019)

The study suggests that for reduced energy expenditure and increased walking distance, providing individuals with a rolling walker is a more favorable option than a standard walker. However, it's essential to acknowledge a potential issue associated with this approach.

- Deal With the Devil?

- Ever heard the story about the sickly woman who makes a deal with the devil who knocks on her door?

- Give me one more year to walk this Earth unharmed, and then you may take my life,” she requests. He happily agrees. She is granted a year, free from injury, but there is no escaping it. Twelve months later, he collects.

- When we hand out a walker, are we making a deal with the devil?

(de Mettelinge & Cambier, 2015)

Providing individuals with a rolling walker can offer reduced energy expenditure and increased walking distance advantages. However, the metaphor of making a deal with the devil suggests that there might be a downside or consequences associated with this choice. It implies that while walkers provide immediate benefits, they may have drawbacks or limitations that therapists must consider when making decisions about assistive devices.

- For so many of these people, once the deal with the devil is struck, natural movement narrows to a 3×2 foot area.

- Because of the fear of falling, there progresses, from that moment, a dearth of risk-taking behavior.

- For these people, falls are a constant threat. This fear translates into an unwillingness to move.

(de Mettelinge & Cambier, 2015)

The metaphor of making a deal with the devil regarding walkers suggests that while these devices provide immediate safety benefits, they might inadvertently discourage individuals from taking risks and challenging their physical limits. The walker, seen as a safety net, can potentially lead to a lack of willingness to engage in activities without it, hindering the individual's ability to recover balance and limiting their overall mobility. The idea is that by prioritizing safety through walkers, therapists may unintentionally contribute to a mindset that avoids necessary challenges for physical improvement.

- We have all seen the “shopping cart push” of a patient with a wheeled walker.

- So what happens when an accident or freak of fate forces that person’s mass outside the carefully maintained base of support?

- Instead of making an easy choice—handing out that walker—therapists need to step back and ponder the antecedent event: what changed?

(de Mettelinge & Cambier, 2015)

The caution against the use of rolling walkers emphasizes the potential drawbacks of these devices. The "Walmart push" scenario, where individuals lean on their rolling walkers like shopping carts, is depicted as a less-than-ideal way to maintain balance and mobility. The argument suggests that therapists should carefully consider the long-term goals and risks associated with different assistive devices, acknowledging that prioritizing immediate safety may not always align with the goal of fostering autonomy and may merely postpone the potential challenges related to balance and falls.

Clinical Reflection

- What short-term changes occur with the use of a supportive device?

- What long-term changes occur with the use of a supportive device?

- Is there a tipping point where it is more dangerous to encourage the use of a supportive device?

- What about autonomy?

The discussion emphasizes the potential long-term consequences of relying on supportive devices. While these devices may offer short-term safety, there is a concern that they can limit an individual's ability to react effectively to unexpected influences or challenges. The mention of situations like navigating through narrow bathroom doors highlights scenarios where dependence on a supportive device might lead to increased vulnerability. The argument suggests that therapists should carefully assess the tipping point where encouraging the use of such devices becomes more dangerous than beneficial.

Method 5: Components of Movement (Part-Task Training)

- Break Activities into Natural Components of Movement.

- The transfer process can be divided into coherent components.

- Start with simple repetitions of basic components or smaller task ranges.

- The practice can evolve to become complex and multifaceted.

- Avoid artificial treatment approaches. Don’t use part-task training for movements that don't naturally break down.

- Apply this method thoughtfully for better outcomes.

The fifth method involves breaking down activities into natural components, often called part-task training. This approach is exemplified through the example of transfer training, where the therapist breaks down the transfer process into distinct components for focused practice. The narrative highlights the significance of recognizing simple and effective components within complex movements. The discussion emphasizes the importance of starting with basic repetitions of smaller tasks, gradually building up to more complex movements. The analogy of an aerobics instructor is used to convey the idea of progressively teaching and integrating components for skill development. The method is considered valuable in teaching and practicing activities, especially in cases where individuals struggle with specific movement components. The importance of ensuring that the breakdown aligns with the natural progression of the movement is emphasized. The example of bed mobility illustrates how this method can effectively address specific challenges within a movement sequence.

A good example is a 15-year-old boy with Down syndrome who faced challenges in a karate class but found success when a compassionate instructor broke down movements into parts and provided repeated practice. The boy's journey from being kicked out of the class to eventually earning a black belt is a powerful illustration of the effectiveness of part-task training. The narrative emphasizes the transformative impact that breaking down movements into manageable components and repetitive practice can have on skill acquisition, particularly for individuals with diverse learning needs. This example underscores the potential for individuals to achieve complexity and mastery through patient and tailored teaching methods.

The discussion now shifts to the concept of part-task training and its application to bed mobility. Bed mobility is identified as an activity that can be effectively broken down into its natural components for targeted training. Focusing on the specific component of pushing with the arm, often challenging for many individuals during bed mobility, can be a productive approach. Individuals can gain the necessary skill and strength by isolating this component and providing repetitive practice. The ultimate goal is to seamlessly integrate these components into the overall movement, allowing for improved bed mobility. This strategy highlights the importance of tailored and systematic training methods in addressing specific challenges within complex movements.

- Break Activities into Natural Components of Movement.

- Let’s look at the common scenario of a patient struggling to get up from a low surface.

- That transfer process can be divided into coherent component parts

Let's look at the common scenario of a patient struggling to get up from a low surface. This is a set of stairs in the pool in the far right image (Figure 2). How can you break it down? Breaking down the action of getting off the sofa or ascending stairs involves a strategic focus on shifting one's buttocks forward. As we discussed, this entails putting your weight forward, rocking, and elongating the buttocks to stretch the muscles. It's a concept I enthusiastically refer to as "power butt" – a reminder that true strength comes from leaning deeply into the movement, ensuring those gluteus muscles are on a substantial stretch.

I often find myself emphasizing the importance of achieving a "power butt" stance. It's not merely about having your butt on stretch; it's about leaning significantly into the movement, unlocking the full potential of those powerful gluteus muscles. The subsequent step involves initiating the rise to stand, seamlessly blending into the rhythmic flow of the entire process.

This approach hinges on breaking down the sequence into distinct component parts, ensuring each element is practiced and refined to attain mastery. Repeating, refining, and seamlessly stitching the components together is cyclical. This methodology mirrors the principles of effective part-task training, a technique I've found to be remarkably successful.

- Getting up off a Low Surface

- Break the act of getting off the couch into shifting buttocks forward, getting the weight forward over legs, rocking, putting buttocks on stretch, initiating rise to stand

- Rolling in Bed

- Break the act of rolling into its segments to figure out where the trouble lies. Often, it is the act of pressing up with your arm, not the rest of the act.

- Getting off the Ground

- Break the act of getting off the floor into its segments. What would happen if the patient scooted over to an ottoman or step? What if he rolled onto his belly? Is there a way to use a pulling motion (using arms)?

Figure 2. Examples of surfaces to practice with part-task training.

Rolling in bed can be deconstructed into various segments to pinpoint potential challenges. The stumbling block often arises precisely at the moment when the elbow struggles to slide underneath the body. This limitation and insufficient tricep engagement hamper the ability to adequately shift weight onto the arm, hindering the pressing-up motion. For many, it's not the rolling itself but the subsequent action of pressing up with the arm that poses a significant challenge.

During my tenure in home health, I consistently advocated for practicing maneuvers on the floor, including getting in and out of the bathtub. I firmly believe in addressing these scenarios proactively to empower individuals with the problem-solving skills necessary to navigate such situations independently. When encountering difficulties, I encourage patients to critically assess their surroundings. Can a sturdy piece of furniture, like an ottoman or a step, be utilized for support? A slight adjustment, like rolling forward onto the belly to a moderate extent, could present a viable solution without resorting to a fully prone position. By fostering a mindset of adaptability and resourcefulness, we can significantly reduce reliance on emergency services for situations that can be managed effectively with thoughtful problem-solving.

Method 6: Variability

- Introduce Variability

- Constant repetition

- Blocked repetition

- Random repetition

- Skill acquisition

(Lage et al, 2015)

The last method I'll discuss before delving into several related topics is introducing variability. Different types of repetition exist, such as constant, blocked, random, and skill acquisition.

Constant repetition involves repeatedly practicing the exact same skill and gradually refining it. For instance, teaching someone to sway back and forth and incorporating additional elements like looking over their shoulder while maintaining the swaying motion.

Blocked repetition entails breaking down a complex skill, like a layup in basketball, into chunks and focusing on each chunk separately. For instance, practicing dribbling acceleration without hip pain, then repeating that specific component.

Random repetition involves weaving together different skills in a random order, requiring individuals to problem-solve and adapt. This challenges them to apply the learned skills in varied situations.

Skill acquisition is the ultimate goal, signifying the mastery of a skill. Notably, a study highlighted the potential dangers of training individuals in skilled nursing to partial competence—where they gain enough strength to perform a task but lack the skill to do it safely. After approximately 50 training sessions, there was a critical threshold before transitioning from partial competence to increased risk, emphasizing the importance of comprehensive skill development and safety awareness.

- What are the limitations of doing simple “blocked” repetition over time?

- Why is random repetition more effective in rehabilitation?

- Variability has a great role in facilitating recall, skill transfer, learning, and retention.

The limitations of simple blocked repetition over time are rooted in diminishing effectiveness. When an activity is repeated consistently without variation, the body adapts and becomes proficient at that specific movement. This adaptation, however, comes at the cost of reduced effectiveness in novel or challenging situations.

An analogy is drawn to using the elliptical machine for exercise. Merely repeating the same motion on the elliptical may lead to diminished workout benefits as the body adjusts to the routine. To counteract this, introducing variation becomes essential. Changing parameters such as resistance, speed, or intensity prevents the body from plateauing and enhances adaptability to diverse scenarios.

Random repetition, involving a mix of skills in an unpredictable manner, proves more effective in rehabilitation. This approach enhances variability, which is crucial in improving recall, skill transfer, learning, and retention. The more diverse the training, the better individuals are prepared to respond effectively to new and unexpected situations. Figure 3 shows a few pool pictures.

Figure 3. Examples of pool activities.

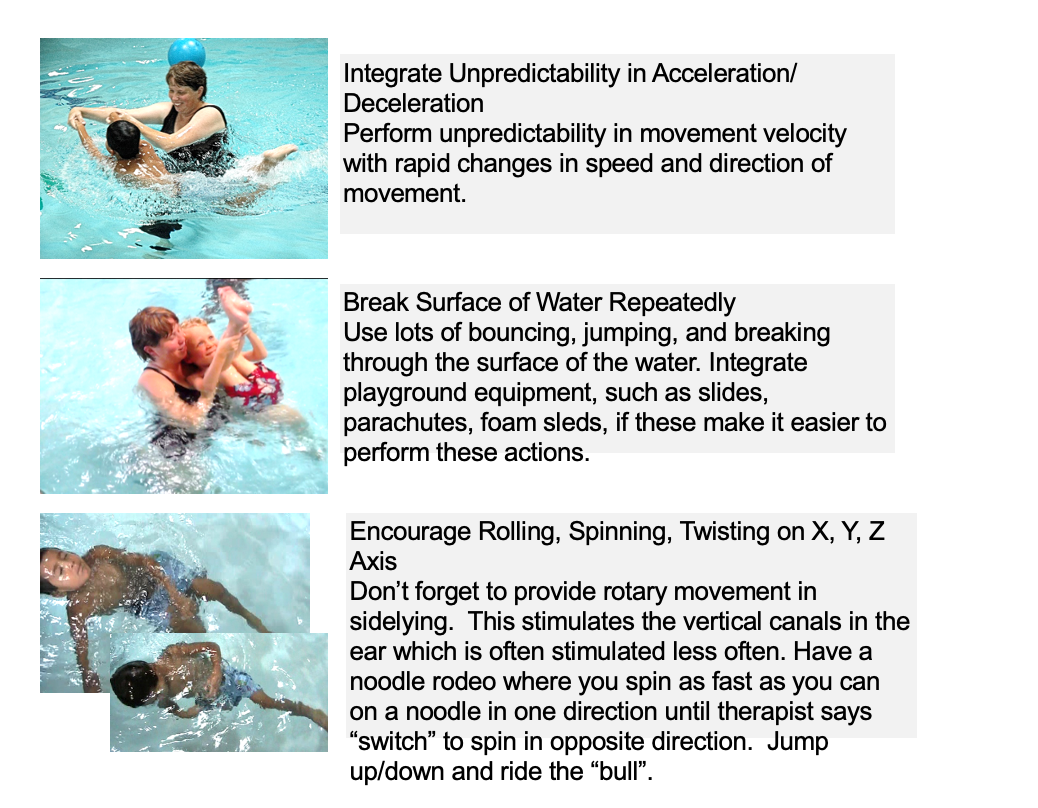

Kiki, a therapist from Aquatic Therapy University, offers a compelling example illustrating the impact of unpredictability on individuals with low tone and arousal, particularly children. When dealing with low-tone individuals, incorporating unpredictable movements, such as acceleration and deceleration, can significantly enhance alertness and arousal. It's not solely about speed but the unpredictability of changes in speed and direction that proves beneficial.

For children with Down syndrome, transitioning them from underwater to above water and back can effectively improve posture and alertness. Bouncing, jumping within safe parameters, and breaking through the water's surface increase alertness. Utilizing tools like slides, parachutes, foam sleds, and flotation mats adds variety and stimulates stability and mobility.

One favorite moment was during a video shoot where the boy spontaneously engaged in an axial roll in the water, reveling in the joy of stimulating his nervous system. This unexpected and self-selected movement highlighted the individual's ability to find activities that personally resonate and contribute to their overall well-being.

Clinical Reflection for Methods 5 and 6

- What are some ways to help you break interventions into component parts?

- What are some ideas for breaking interventions into component parts?

- Seth Godin’s Edgecraft

(Yip, 2020)

Edgecraft, a term introduced by Seth Godin in a marketing context, focuses on finding aspects on the edge of the ordinary and pushing them further to create buzz and engagement. In the example given, for a new restaurant, the suggestion was to have only twins as waiters and waitresses to make it remarkable and conversation-worthy.

In a therapeutic context, edgecraft can be applied to motivate individuals towards their goals. Instead of conventional approaches, finding unique and personalized ways to make therapy engaging and memorable might be the key. Identifying what is on the edge for an individual and pushing past that edge in a positive and constructive manner could enhance their motivation and commitment to the therapeutic process.

- Desired Skill: Patient will be able to hold tandem stance independently for 30 seconds.

- To "Edgecraft":

- Find the characteristic or trait that is unique or remarkable about your patient’s impairment.

- Go all the way to the ‘edge’ of that characteristic.

- Play back and forth across the edge.

- I try to let my patients win 51% of the time.

My desired skill was for patients to be able to hold a tandem stance or to be able to sit unsupported on the side of the bed for 30 seconds. I will find the characteristic or trait that is unique or remarkable about their impairment. An example is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Someone doing a tandem stance.

Identifying the factors that hinder a person from performing a particular task involves understanding their natural boundaries or limitations. This can be assessed through tests like the Berg, Tinetti, or ADL tests. By pinpointing an individual's specific challenges, therapists can determine the natural boundary, which is essentially the problem area.

Once the natural boundary is identified, therapy involves pushing individuals to the edge of that limitation and engaging in activities that play back and forth across that edge. The aim is to let the patients learn and succeed without experiencing a loss of balance, but therapists must be ready to step in and provide support if needed. The emphasis is on allowing patients to attempt tasks and experience a sense of accomplishment before any necessary intervention. This approach encourages individuals to challenge themselves and build confidence in their abilities.

In Conclusion: Methods

- Physical and occupational therapists who learn to use methods of progression like the 6 discussed will have a nearly endless source of ideas for treatment.

I often share quick and practical ideas in the therapy room to keep things engaging and dynamic. Sometimes, therapists, like anyone else, can find themselves in a bit of a rut and need inspiration. So, here are some take-home ideas, a little collection to serve as reminders or anticipation for the next session.

Consider this single slide – a snapshot of creativity. I understand that even in the noble pursuit of helping people, therapists can experience boredom. To combat this, I suggest printing out this slide. Picture this: you're in a session, feeling uninspired, and you glance at this reminder. It might just be the nudge to infuse creative energy into the moment.

For example, when faced with the task of encouraging more rolling in bed, try this: have your clients lie on top of the sheets. Challenge them to slip under the sheets without sitting up and time it using a clock. It turns a seemingly simple exercise into a playful challenge. I've done this with patients, and we end up laughing together. They might express disbelief, "Why would I do this? I can't sit up like that!" I respond, "I don't know, but you're incredible, you're amazing, and I'm enjoying every moment of this." The enjoyment becomes mutual, turning a routine task into a delightful experience for both therapist and patient.

Intervention Ideas: Methods

- Here are a few “takeaway” ideas from today’s session:

- Add music

- Add water

- Stop helping

- Ditch the walker

- Reduce task attention

- Find the failure point

- Require buy-in

- Don’t over-simplify

- Mix it up

- Give (or withdraw) feedback

- Design part-to-whole

- Do the same activity with a different focus

- Return to earlier developmental stages

Above are some ideas to keep in mind.

Intervention Ideas: Methods: Add Music

- Add Music: Researchers have found that adding an extra layer to physical exercise can work wonders for cognitive function. Connecting mind and body with music (especially familiar songs) will deepen that cognitive connection and may improve balance.

- It is also possible to use entrainment, a physical and cognitive trait often associated with the perception of music; using entrainment, a patient moves their body parts to the beat of the music.

(Satoh et al., 2017)

Incorporating music into therapeutic sessions can add a transformative dimension to physical activities. I'm exploring a new aquatic technique involving therapeutic listening to music during activities like watsu. Researchers have found that introducing an extra layer, especially in cases like dementia patients, can yield remarkable results. Music has a unique ability to evoke emotions and trigger memories, as seen in instances where patients with conditions like Parkinson's or those who are non-verbal for extended periods suddenly engage or even start singing when exposed to music.

I have a colleague, Stacy, who teaches aquatic therapy and shared a remarkable experience. He worked with a Parkinson's patient who had a flat affect and limited emotional connection. Taking him into the swimming pool, Stacy encountered a moment where a subtle shift in the patient's weight triggered an unexpected swimming response. It's akin to the impact of music, where individuals who have been silent for extended periods find their voice when exposed to melodies or hymns. Music serves as a potent connector, tapping into deep emotional reserves.

Entrainment, a concept familiar to me as a band enthusiast, plays a pivotal role. It reflects the natural tendency of the human body to synchronize with external beats. This principle is akin to using a metronome, providing an external cue that guides and synchronizes movements, enhancing the therapeutic impact of physical activities.

Intervention Ideas: Methods: Add Water

- Add Water: It is also possible to layer physical exercise with immersion to deepen these neural connections.