You'll have to ask your doctor why the hell edaravone is approved in Japan since 2001 but not the US.

Has your stroke hospital done anything with edaravone in the last decade?

edaravone (12 posts to November 2011)

Ebselen, an anti-inflammatory antioxidant, was originally developed by Daiichi Sankyo, in Japan, to treat patients who had suffered a stroke. But the compound was never marketed and has since come off patent. It’s also part of the National Institutes of Health Clinical Collection—several hundred small molecules that have, to some extent, gone through the gamut of human clinical trials and have been found to be safe, but never reached final FDA approval.

ebselen (10 posts to December 2012)

Carnosic Acid Shows Higher Neuroprotective Efficiency than Edaravone or Ebselen in In Vitro Models of Neuronal Cell Damage

1

Maj Institute of Pharmacology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Department of Experimental Neuroendocrinology, 31-343 Krakow, Poland

2

Jerzy Haber Institute of Catalysis and Surface Chemistry, Polish Academy of Sciences, 30-239 Krakow, Poland

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Molecules 2024, 29(1), 119; https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29010119

Original submission received: 19 October 2023

/

Resubmission received: 16 November 2023

/

Revised: 21 December 2023

/

Accepted: 22 December 2023

/

Published: 24 December 2023

Abstract

This study compared the neuroprotective efficacy of

three antioxidants—the plant-derived carnosic acid (CA), and two

synthetic free radical scavengers: edaravone (ED) and ebselen (EB)—in in

vitro models of neuronal cell damage. Results showed that CA protected

mouse primary neuronal cell cultures against hydrogen peroxide-induced

damage more efficiently than ED or EB. The neuroprotective effects of CA

were associated with attenuation of reactive oxygen species level and

increased mitochondrial membrane potential but not with a reduction in

caspase-3 activity. None of the tested substances was protective against

glutamate or oxygen-glucose deprivation-evoked neuronal cell damage,

and EB even increased the detrimental effects of these insults. Further

experiments using the human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells showed that CA

but not ED or EB attenuated the cell damage induced by hydrogen peroxide

and that the composition of culture medium is the critical factor in

evaluating neuroprotective effects in this model. Our data indicate that

the neuroprotective potential of CA, ED, and EB may be revealed in

vitro only under specific conditions, with their rather narrow

micromolar concentrations, relevant cellular model, type of toxic agent,

and exposure time. Nevertheless, of the three compounds tested, CA

displayed the most consistent neuroprotective effects.

1. Introduction

Oxidative

stress has long been recognized as the pivotal component of neuronal

death in both acute (stroke, traumatic brain injury) and chronic

neurodegenerative dis-eases, e.g., Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and

Huntington’s disease [1,2,3].

It has been well established that oxidative stress results from a

disturbed balance between the excessive intracellular accumulation of

reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and

endogenous antioxidant defense system in which glutathione peroxidase,

glutathione reductase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase play the

critical role [4].

The ROS and RNS in high concentrations are directly damaging factors

for lipids, carbohydrates, amino acids, proteins and nucleic acids, in

this way disrupting intracellular organelles, structural proteins and

membranes [5,6].

Therefore, the removal of pathologically produced free radicals has

been proposed as a viable neuroprotective strategy. Besides

anti-oxidative enzymes, vitamins A, C and E, glutathione, plant

polyphenolic compounds including flavonoids, thioredoxin,

metallothionein, ceruloplasmin, and some trace elements can alleviate

the harmful effects of ROS and RNS [2].

Although natural antioxidants show high activity in the scavenging of

free radicals, their bioavailability is limited by low absorption and

poor stability [7].

Regarding synthetic antioxidants, some compounds with strong free

radical scavenging properties or free radical trapping activities (e.g.,

NXY-059—disufenton sodium and its derivatives) showed only modest

neuroprotective activity and a bell-shaped dose–response curve in in

vivo experimental models of neuronal damage. Moreover, in clinical

trials, they failed to show consistent neuroprotective effects over

placebo [8].

It should be mentioned here that clinical trials on the neuroprotective

potential of antioxidants were conducted among small study populations [3].

On the other hand, some antioxidative compounds such as gallic acid

esters, hydroxytoluene, and butylated hydroxyanisole display undesired

effects on living organisms [9].

Among antioxidants with potential translational value, low molecular

weight, and cell membrane-permeable superoxide dismutase mimetics, such

as the nitroxide tempol

(4-hydroxyl-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl), seem quite promising [10].

The inconsistent results of studies on the neuroprotective effects of

antioxidants are thought to be due to unfavorable pharmacokinetic

profiles, i.e., low water solubility and bioavailability, difficult

penetration through the blood–brain barrier (BBB), uncertain stability,

and insufficient knowledge of their metabolism and elimination. Another

problem concerns establishing therapeutic concentrations of antioxidants

in blood and brain tissue because, depending on their concentrations,

these compounds may exert antioxidative or prooxidative effects. One of

the methods to improve the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic

properties of antioxidants is their encapsulation in nanoparticles

(nanocarriers) [11,12].

However, before this step, it is essential to select the most promising

antioxidant among various candidates in the same screening platforms

for neuroprotection.

Based on the literature

search, we have chosen three hydrophobic compounds with antioxidant

properties: edaravone, ebselen, and carnosic acid. Edaravone (ED,

MCI-186, 3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one, Figure 1A)

is a clinical drug developed by Mitsubishi Tanaba (Osaka, Japan) and

has been approved by Japan and the FDA for ALS treatment since 2015 and

2017, respectively [13].

It is a free radical scavenger with the capacity to mitigate oxidative

injury in various models of neuronal damage. The protective effects of

ED in attenuating NO, glutamate, and hypoxia-induced cytotoxicity and

apoptosis have been reported [14,15,16,17]. ED also effectively protects astrocytes from oxidative stress or infectious insults such as bacterial lipopolysaccharides [18]. Ebselen (EB, 2-phenyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-one, Figure 1B) is an organoselenium compound with well-characterized toxicology and pharmacology [19].

Its antioxidative mechanism of action involves glutathione

peroxidase-like activity and ability to react with thiols,

peroxynitrites, and hydroperoxides. EB protects cell components from

oxidative damage [20,21].

EB and its analogues showed neuroprotective effects in various

experimental models against cell damage induced by oxygen and glucose

deprivation (OGD), amyloid β(1-42), lipopolysaccharide,

6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), and in MPTP-treated mice [22,23,24,25,26].

Carnosic acid (CA,

4aR,10aS)-5,6-dihydroxy-7-isopropyl-1,1-dimethyl-1,3,4,9,10,10a-hexahydro-2H-phenanthrene-4a-carboxylic

acid, Figure 1C)

isolated from rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) and common sage (Salvia

officinalis) possesses antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and

anti-neoplastic properties [27,28,29].

CA was found to ameliorate oxidative stress-, glutamate-, and

hypoxia-induced injury of neuronal as well as displayed neuroprotective

activity in in vitro and in vivo models of Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s

disease [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39].

Although most of the above-cited studies

unanimously indicate the neuroprotective effects of ED, EB, and CA, they

differ in experimental settings, doses of compounds, times of

exposures, and measurements of cellular damages, etc., which makes their

comparison difficult. Therefore, in order to select the most promising

neuroprotective compound of those three for nanoencapsulation for future

experimental studies, it was necessary to estimate their properties

under similar, well-controlled conditions. Thus, in the present study,

we compared biocompatibility and neuroprotective potentials of ED, EB,

and CA in a wide range of concentrations in mouse primary neuronal cell

cultures exposed to oxidative stress inducer (hydrogen peroxide, H2O2),

excitotoxic factor (glutamate), and OGD. Moreover, some protective

mechanisms were studied for the best-acting neuroprotectant. Finally,

biosafety and neuroprotective profiles of these three compounds were

also tested in the human neuronal-like model: undifferentiated (UN-) and

retinoic acid-differentiated (RA-) neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells exposed

to H2O2.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. The Effect of Edaravone in Primary Neuronal Cell Cultures

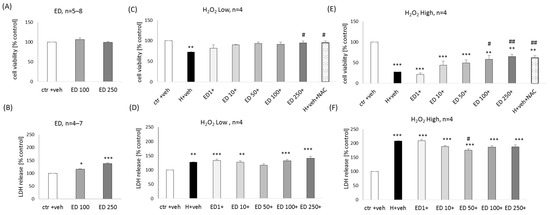

ED at concentrations of 100 and 250 μM did not evoke any reduction in cell viability in primary neuronal cell cultures (Figure 2A) but slightly increased the LDH release (17–37%) (Figure 2B).

A significant neuroprotective effect of ED (100 and 250 μM) was found

in the model of neuronal cell damage induced by lower (150 μM) and

higher (200 μM) concentrations of H2O2 at the

level of the cell viability assessment. This effect was comparable to

protection mediated by positive control, NAC (1 mM) (99.28% and

94.15–105.29% of NAC efficiency for low and high H2O2, respectively) (Figure 2C,E). In the cytotoxicity assay, a slight reduction was observed of the high H2O2-evoked changes in this parameter by ED at a concentration of 50 μM (Figure 2F), but no impact of ED was found on low H2O2-induced LDH release (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Biosafety (A,B) and neuroprotection (C–F) assessment against the hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced

cell damage by edaravone (ED) in primary neuronal cell cultures. The

eight days in vitro cortical neurons were treated either with vehicle or

with ED alone (100 and 250 μM) or ED (1–250 μM) in combination with low

(150 μM) or high (200 μM) concentrations of H2O2 for 24 h. An antioxidant N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC, 1 mM) was used as a positive control of the model. Cell viability (A,C,E) and cytotoxicity (B,D,F)

were measured by MTT reduction and LDH release assays, respectively.

The data were normalized to vehicle-treated cells and presented as the

mean ± SEM. The number of independent experiments (n) is indicated in each graph. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001 vs. vehicle-treated cells; # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. H2O2-treated cells.

More at link.

No comments:

Post a Comment