You don't want the reduced cerebral blood flow which you already had as part of your stroke. You can ask your doctor what protocol they used to correct that reduced flow; if they did nothing you don't have a functioning stroke doctor. This is why I'm vaccinated up the wazoo.

This is what I'm going to tell my doctor to do; don't listen to me,I'm not medically trained.

If your doctor has DONE NOTHING on cerebral blood flow and oxygenation then you don't have a functioning stroke doctor or hospital.

cerebral blood flow (27 posts to July 2016)

oxygenation (5 posts to March 2013)

The latest here:

Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations

Nature Reviews Microbiology (2023)

Abstract

Long COVID is an often debilitating illness that occurs in at least 10% of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections. More than 200 symptoms have been identified with impacts on multiple organ systems. At least 65 million individuals worldwide are estimated to have long COVID, with cases increasing daily. Biomedical research has made substantial progress in identifying various pathophysiological changes and risk factors and in characterizing the illness; further, similarities with other viral-onset illnesses such as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome have laid the groundwork for research in the field. In this Review, we explore the current literature and highlight key findings, the overlap with other conditions, the variable onset of symptoms, long COVID in children and the impact of vaccinations. Although these key findings are critical to understanding long COVID, current diagnostic and treatment options are insufficient, and clinical trials must be prioritized that address leading hypotheses. Additionally, to strengthen long COVID research, future studies must account for biases and SARS-CoV-2 testing issues, build on viral-onset research, be inclusive of marginalized populations and meaningfully engage patients throughout the research process.

Introduction

Long COVID (sometimes referred to as ‘post-acute sequelae of COVID-19’) is a multisystemic condition comprising often severe symptoms that follow a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. At least 65 million individuals around the world have long COVID, based on a conservative estimated incidence of 10% of infected people and more than 651 million documented COVID-19 cases worldwide1; the number is likely much higher due to many undocumented cases. The incidence is estimated at 10–30% of non-hospitalized cases, 50–70% of hospitalized cases2,3 and 10–12% of vaccinated cases4,5. Long COVID is associated with all ages and acute phase disease severities, with the highest percentage of diagnoses between the ages of 36 and 50 years, and most long COVID cases are in non-hospitalized patients with a mild acute illness6, as this population represents the majority of overall COVID-19 cases. There are many research challenges, as outlined in this Review, and many open questions, particularly relating to pathophysiology, effective treatments and risk factors.

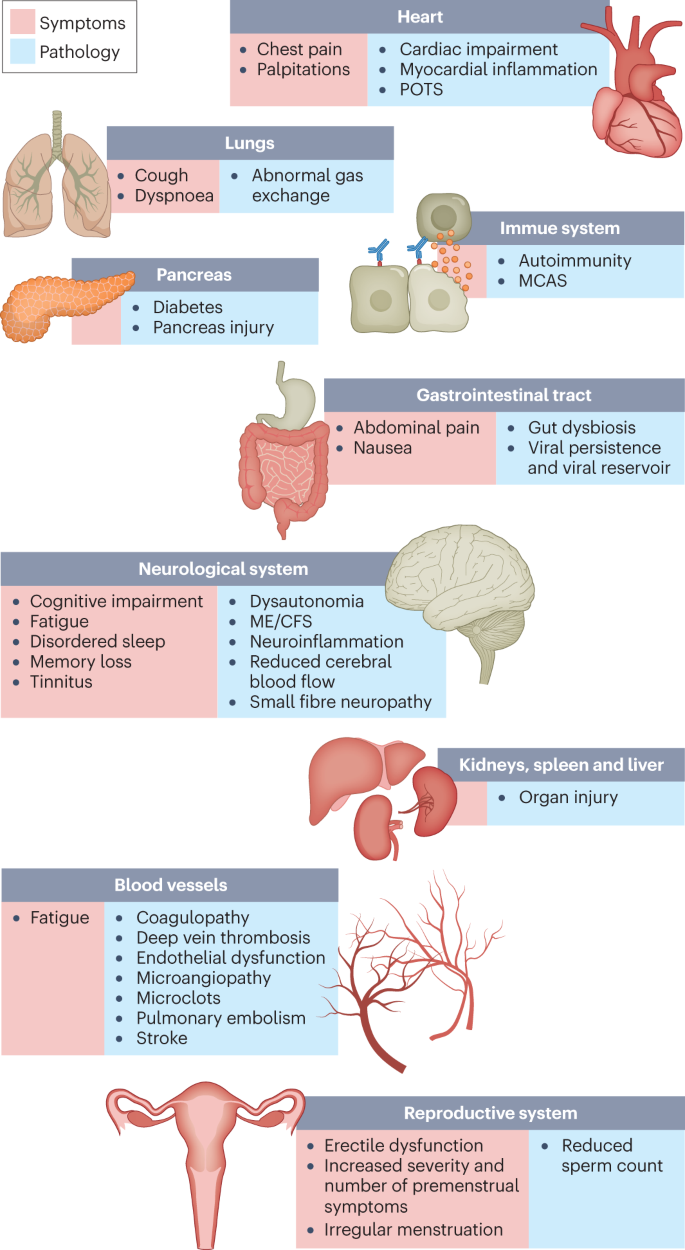

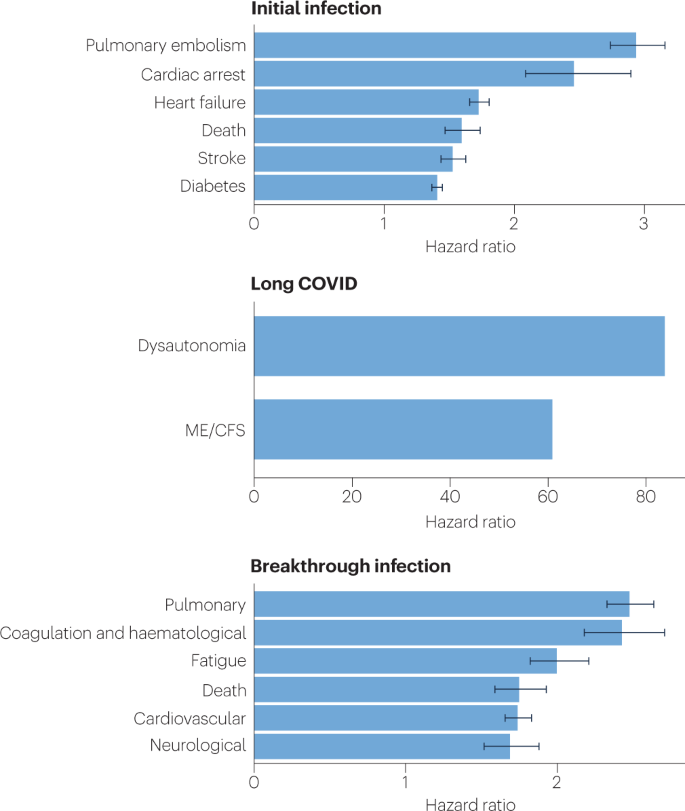

Hundreds of biomedical findings have been documented, with many patients experiencing dozens of symptoms across multiple organ systems7 (Fig. 1). Long COVID encompasses multiple adverse outcomes, with common new-onset conditions including cardiovascular, thrombotic and cerebrovascular disease8, type 2 diabetes9, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)10,11 and dysautonomia, especially postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS)12 (Fig. 2). Symptoms can last for years13, and particularly in cases of new-onset ME/CFS and dysautonomia are expected to be lifelong14. With significant proportions of individuals with long COVID unable to return to work7, the scale of newly disabled individuals is contributing to labour shortages15. There are currently no validated effective treatments.

The impacts of long COVID on numerous organs with a wide variety of pathology are shown. The presentation of pathologies is often overlapping, which can exacerbate management challenges. MCAS, mast cell activation syndrome; ME/CFS, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome; POTS, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

Because diagnosis-specific data on large populations with long COVID are sparse, outcomes from general infections are included and a large proportion of medical conditions are expected to result from long COVID, although the precise proportion cannot be determined. One year after the initial infection, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections increased the risk of cardiac arrest, death, diabetes, heart failure, pulmonary embolism and stroke, as studied with use of US Department of Veterans Affairs databases. Additionally, there is clear increased risk of developing myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and dysautonomia. Six months after breakthrough infection, increased risks were observed for cardiovascular conditions, coagulation and haematological conditions, death, fatigue, neurological conditions and pulmonary conditions in the same cohort. The hazard ratio is the ratio of how often an event occurs in one group relative to another; in this case people who have had COVID-19 compared with those who have not. Data sources are as follows: diabetes9, cardiovascular outcomes8, dysautonomia8,201, ME/CFS10,202 and breakthrough infections4.

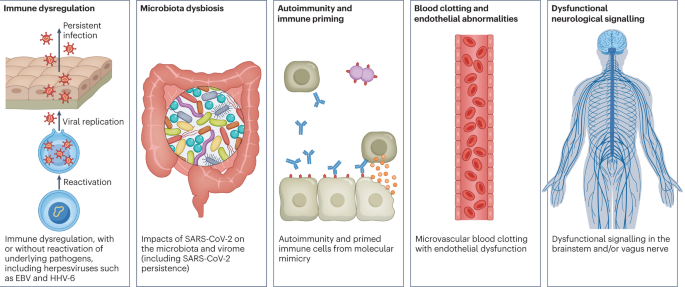

There are likely multiple, potentially overlapping, causes of long COVID. Several hypotheses for its pathogenesis have been suggested, including persisting reservoirs of SARS-CoV-2 in tissues16,17; immune dysregulation17,18,19,20 with or without reactivation of underlying pathogens, including herpesviruses such as Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) among others17,18,21,22; impacts of SARS-CoV-2 on the microbiota, including the virome17,23,24,25; autoimmunity17,26,27,28 and priming of the immune system from molecular mimicry17; microvascular blood clotting with endothelial dysfunction17,29,30,31; and dysfunctional signalling in the brainstem and/or vagus nerve17,32 (Fig. 3). Mechanistic studies are generally at an early stage, and although work that builds on existing research from postviral illnesses such as ME/CFS has advanced some theories, many questions remain and are a priority to address. Risk factors potentially include female sex, type 2 diabetes, EBV reactivation, the presence of specific autoantibodies27, connective tissue disorders33, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, chronic urticaria and allergic rhinitis34, although a third of people with long COVID have no identified pre-existing conditions6. A higher prevalence of long Covid has been reported in certain ethnicities, including people with Hispanic or Latino heritage35. Socio-economic risk factors include lower income and an inability to adequately rest in the early weeks after developing COVID-19 (refs. 36,37). Before the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, multiple viral and bacterial infections were known to cause postinfectious illnesses such as ME/CFS17,38, and there are indications that long COVID shares their mechanistic and phenotypic characteristics17,39. Further, dysautonomia has been observed in other postviral illnesses and is frequently observed in long COVID7.

There are several hypothesized mechanisms for long COVID pathogenesis, including immune dysregulation, microbiota disruption, autoimmunity, clotting and endothelial abnormality, and dysfunctional neurological signalling. EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; HHV-6, human herpesvirus 6; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

In this Review, we explore the current knowledge base of long COVID as well as misconceptions surrounding long COVID and areas where additional research is needed. Because most patients with long COVID were not hospitalized for their initial SARS-CoV-2 infection6, we focus on research that includes patients with mild acute COVID-19 (meaning not hospitalized and without evidence of respiratory disease). Most of the studies we discuss refer to adults, except for those in Box 1.

More at link.

No comments:

Post a Comment