Lets get some more hyperacute research on this.

Novel drug candidates offer new route to controlling inflammation

Pursuing a relatively untapped route for regulating the immune system, an international team of researchers has designed and conducted initial tests on molecules that have the potential to treat diseases involving inflammation, such as asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, stroke and sepsis.

The team started by creating a three-dimensional map of a protein structure called the C3a receptor, which sits on the surface of human cells and plays a critical role in regulating a branch of the immune system called the complement system. They then used computational techniques to design short portions of protein molecules, known as peptides, that they predicted would interact with the receptor and either block or enhance aspects of its activity. Finally, experimentalists validated the theoretical predictions by synthesizing the peptides and testing them in animal and human cells.

The researchers – a collaboration of teams at four institutions on three continents – published their results May 10 in the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.

The collaboration includes Christodoulos Floudas, the Stephen C. Macaleer '63 Professor of Engineering and Applied Science in the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering at Princeton University; Dimitrios Morikis, professor of bioengineering at the University of California, Riverside; Peter Monk of the Department of Infection and Immunity at the University of Sheffield Medical School, U.K.; and Trent Woodruff of the School of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Queensland, Australia.

The regulation of the complement system – so called because it complements the body's central system of immune cells and antibodies – is thought to be a possible route to controlling over-active or mistaken immune responses that cause damage. However, few drugs directly target complement proteins, and none targets the C3a receptor, in part because of the complexity of the complement system. In some cases complement activity can help downplay immune responses while in other cases it can stroke even stronger reactions.

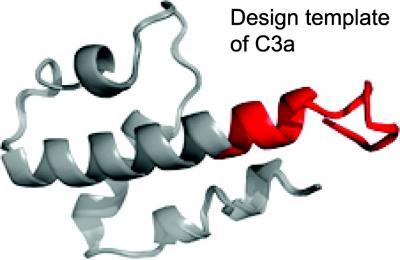

An international team created drug candidates based on the naturally

occurring C3a peptide, the chain of molecules shown here. The C3a

peptide is a key player in regulating immune responses and drugs that

enhance or block its effects could be useful in treating many

inflammatory diseases.

(Photo Credit: Journal of Medicinal Chemistry)

(Photo Credit: Journal of Medicinal Chemistry)

Morikis and his graduate students Chris Kieslich and Li Zhang provided the collaborators the 3D structure of the naturally occurring peptide that normally regulates the C3a receptor in human cells. Using a portion of that structure as a flexible template, Floudas and graduate students Meghan Bellows-Peterson and Ho Ki Fung designed new peptides that were predicted either to enhance or block C3a. Monk and postdoctoral fellow Kathryn Wareham tested the predictions in rat cells, while Woodruff and student Owen Hawksworth tested them in human cells.

Among the conditions potentially treatable through complement regulation is reperfusion injury, which occurs when blood flow is temporarily cut off to some part of the body, as in a heart attack or stroke, and then an inflammatory response develops when the blood returns. Another possible use would be in organ transplantation, in which the body often mounts a destructive immune response against the newly introduced organ. Other common conditions affected by the complement system are rheumatoid arthritis and sepsis.

As next steps, the team will seek to test their peptides in live animal models of inflammation. They also plan to explore more generally the dual role of C3a in inflammation, with an eye toward developing further drug candidates.

No comments:

Post a Comment