In mice, so your doctor and stroke hospital have followup to to to ensure this gets tested in humans. With tens of thousands of doctors and stroke hospital presidents calling for this research it would get done. Their responsibility, if they fail at this, call the board of directors and ask when competent people will be employed.

Johns Hopkins Breakthrough Opens the Door for Stem Cell Transplants to Repair the Brain

Transplanted brain stem cells survive without anti-rejection

drugs in mice. By exploiting a feature of the immune system, researchers

open the door for stem cell transplants to repair the brain.

In experiments in mice, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers say they

have developed a way to successfully transplant certain protective brain

cells without the need for lifelong anti-rejection drugs.

A report on the research, published today (September 16, 2019) in the journal Brain, details the new approach, which selectively circumvents the immune response against foreign cells, allowing transplanted cells to survive, thrive and protect brain tissue long after stopping immune-suppressing drugs.

A report on the research, published today (September 16, 2019) in the journal Brain, details the new approach, which selectively circumvents the immune response against foreign cells, allowing transplanted cells to survive, thrive and protect brain tissue long after stopping immune-suppressing drugs.

The ability to successfully transplant healthy cells into the brain

without the need for conventional anti-rejection drugs could advance the

search for therapies that help children born with a rare but

devastating class of genetic diseases in which myelin, the protective

coating around neurons that helps them send messages, does not form

normally. Approximately 1 of every 100,000 children born in the U.S.

will have one of these diseases, such as Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease.

This disorder is characterized by infants missing developmental

milestones such as sitting and walking, having involuntary muscle

spasms, and potentially experiencing partial paralysis of the arms and

legs, all caused by a genetic mutation in the genes that form myelin.

“Because these conditions are initiated by a mutation causing dysfunction in one type of cell, they present a good target for cell therapies, which involve transplanting healthy cells or cells engineered to not have a condition to take over for the diseased, damaged or missing cells,” says Piotr Walczak, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of radiology and radiological science at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

A major obstacle to our ability to replace these defective cells is the mammalian immune system. The immune system works by rapidly identifying ‘self’ or ‘nonself’ tissues, and mounting attacks to destroy nonself or “foreign” invaders. While beneficial when targeting bacteria or viruses, it is a major hurdle for transplanted organs, tissue or cells, which are also flagged for destruction. Traditional anti-rejection drugs that broadly and unspecifically tamp down the immune system altogether frequently work to fend off tissue rejection, but leave patients vulnerable to infection and other side effects. Patients need to remain on these drugs indefinitely.

In a bid to stop the immune response without the side effects, the Johns Hopkins Medicine team sought ways to manipulate T cells, the system’s elite infection-fighting force that attacks foreign invaders.

Specifically, Walczak and his team focused on the series of so-called “costimulatory signals” that T cells must encounter in order to begin an attack.

“These signals are in place to help ensure these immune system cells do not go rogue, attacking the body’s own healthy tissues,” says Gerald Brandacher, M.D., professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery and scientific director of the Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation Research Laboratory at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and co-author of this study.

The idea, he says, was to exploit the natural tendencies of these costimulatory signals as a means of training the immune system to eventually accept transplanted cells as “self” permanently.

To do that, the investigators used two antibodies, CTLA4-Ig and anti-CD154, which keep T cells from beginning an attack when encountering foreign particles by binding to the T cell surface, essentially blocking the ‘go’ signal. This combination has previously been used successfully to block rejection of solid organ transplants in animals, but had not yet been tested for cell transplants to repair myelin in the brain, says Walczak.

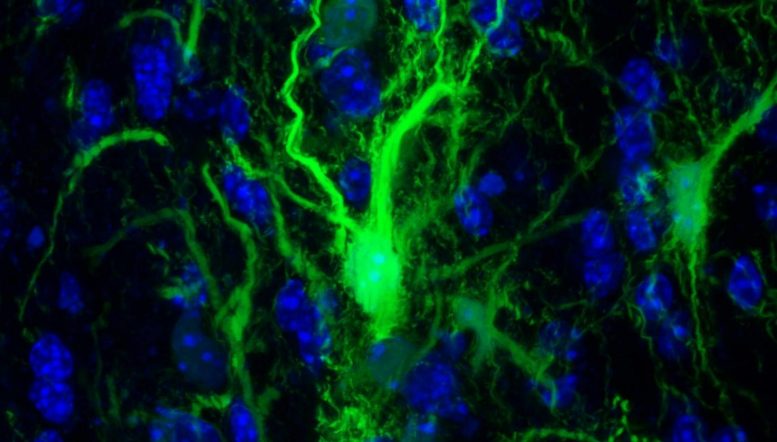

In a key set of experiments, Walczak and his team injected mouse brains with the protective glial cells that produce the myelin sheath that surrounds neurons. These specific cells were genetically engineered to glow so the researchers could keep tabs on them.

The researchers then transplanted the glial cells into three types of mice: mice genetically engineered to not form the glial cells that create the myelin sheath, normal mice and mice bred to be unable to mount an immune response.

Then the researchers used the antibodies to block an immune response, stopping treatment after six days.

Each day, the researchers used a specialized camera that could detect the glowing cells and capture pictures of the mouse brains, looking for the relative presence or absence of the transplanted glial cells. Cells transplanted into control mice that did not receive the antibody treatment immediately began to die off, and their glow was no longer detected by the camera by day 21.

The mice that received the antibody treatment maintained significant levels of transplanted glial cells for over 203 days, showing they were not killed by the mouse’s T cells even in the absence of treatment.

“The fact that any glow remained showed us that cells had survived transplantation, even long after stopping the treatment,” says Shen Li, M.D., lead author of the study. “We interpret this result as a success in selectively blocking the immune system’s T cells from killing the transplanted cells.”

The next step was to see whether the transplanted glial cells survived well enough to do what glial cells normally do in the brain — create the myelin sheath. To do this, the researchers looked for key structural differences between mouse brains with thriving glial cells and those without, using MRI images. In the images, the researchers saw that the cells in the treated animals were indeed populating the appropriate parts of the brain.

Their results confirmed that the transplanted cells were able to thrive and assume their normal function of protecting neurons in the brain.

Walczak cautioned that these results are preliminary. They were able to deliver these cells and allow them to thrive in a localized portion of the mouse brain.

In the future, they hope to combine their findings with studies on cell delivery methods to the brain to help repair the brain more globally.

###

Other researchers involved in this study include Byoung Chol Oh, Chengyan Chu, Antje Arnold, Anna Jablonska, Georg Furtmüller, Huamin Qin and Miroslaw Janowski of The Johns Hopkins University; Shen Li of the Dalian Municipal Central Hospital and The Johns Hopkins University; Johannes Boltze of the University of Warwick; and Tim Magnus and Peter Ludewig of the University of Hamburg.

Reference: “Induction of immunological tolerance to myelinogenic

glial-restricted progenitor allografts” by Shen Li, Byoung Chol Oh,

Chengyan Chu, Antje Arnold, Anna Jablonska, Georg J Furtmüller, Hua-Min

Qin, Johannes Boltze, Tim Magnus, Peter Ludewig, Mirosław Janowski,

Gerald Brandacher and Piotr Walczak, 16 September 2019, Brain.“Because these conditions are initiated by a mutation causing dysfunction in one type of cell, they present a good target for cell therapies, which involve transplanting healthy cells or cells engineered to not have a condition to take over for the diseased, damaged or missing cells,” says Piotr Walczak, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of radiology and radiological science at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

A major obstacle to our ability to replace these defective cells is the mammalian immune system. The immune system works by rapidly identifying ‘self’ or ‘nonself’ tissues, and mounting attacks to destroy nonself or “foreign” invaders. While beneficial when targeting bacteria or viruses, it is a major hurdle for transplanted organs, tissue or cells, which are also flagged for destruction. Traditional anti-rejection drugs that broadly and unspecifically tamp down the immune system altogether frequently work to fend off tissue rejection, but leave patients vulnerable to infection and other side effects. Patients need to remain on these drugs indefinitely.

In a bid to stop the immune response without the side effects, the Johns Hopkins Medicine team sought ways to manipulate T cells, the system’s elite infection-fighting force that attacks foreign invaders.

Specifically, Walczak and his team focused on the series of so-called “costimulatory signals” that T cells must encounter in order to begin an attack.

“These signals are in place to help ensure these immune system cells do not go rogue, attacking the body’s own healthy tissues,” says Gerald Brandacher, M.D., professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery and scientific director of the Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation Research Laboratory at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and co-author of this study.

The idea, he says, was to exploit the natural tendencies of these costimulatory signals as a means of training the immune system to eventually accept transplanted cells as “self” permanently.

To do that, the investigators used two antibodies, CTLA4-Ig and anti-CD154, which keep T cells from beginning an attack when encountering foreign particles by binding to the T cell surface, essentially blocking the ‘go’ signal. This combination has previously been used successfully to block rejection of solid organ transplants in animals, but had not yet been tested for cell transplants to repair myelin in the brain, says Walczak.

In a key set of experiments, Walczak and his team injected mouse brains with the protective glial cells that produce the myelin sheath that surrounds neurons. These specific cells were genetically engineered to glow so the researchers could keep tabs on them.

The researchers then transplanted the glial cells into three types of mice: mice genetically engineered to not form the glial cells that create the myelin sheath, normal mice and mice bred to be unable to mount an immune response.

Then the researchers used the antibodies to block an immune response, stopping treatment after six days.

Each day, the researchers used a specialized camera that could detect the glowing cells and capture pictures of the mouse brains, looking for the relative presence or absence of the transplanted glial cells. Cells transplanted into control mice that did not receive the antibody treatment immediately began to die off, and their glow was no longer detected by the camera by day 21.

The mice that received the antibody treatment maintained significant levels of transplanted glial cells for over 203 days, showing they were not killed by the mouse’s T cells even in the absence of treatment.

“The fact that any glow remained showed us that cells had survived transplantation, even long after stopping the treatment,” says Shen Li, M.D., lead author of the study. “We interpret this result as a success in selectively blocking the immune system’s T cells from killing the transplanted cells.”

The next step was to see whether the transplanted glial cells survived well enough to do what glial cells normally do in the brain — create the myelin sheath. To do this, the researchers looked for key structural differences between mouse brains with thriving glial cells and those without, using MRI images. In the images, the researchers saw that the cells in the treated animals were indeed populating the appropriate parts of the brain.

Their results confirmed that the transplanted cells were able to thrive and assume their normal function of protecting neurons in the brain.

Walczak cautioned that these results are preliminary. They were able to deliver these cells and allow them to thrive in a localized portion of the mouse brain.

In the future, they hope to combine their findings with studies on cell delivery methods to the brain to help repair the brain more globally.

###

Other researchers involved in this study include Byoung Chol Oh, Chengyan Chu, Antje Arnold, Anna Jablonska, Georg Furtmüller, Huamin Qin and Miroslaw Janowski of The Johns Hopkins University; Shen Li of the Dalian Municipal Central Hospital and The Johns Hopkins University; Johannes Boltze of the University of Warwick; and Tim Magnus and Peter Ludewig of the University of Hamburg.

No comments:

Post a Comment