Didn't your incompetent? doctor work on this much earlier? NO? So, you finally realized you do have an incompetent doctor! Incompetence is NOT getting you 100% recovered! What are you going to do about that?

Parvalbumin interneurons regulate rehabilitation-induced functional recovery after stroke and identify a rehabilitation drug

Nature Communications volume 16, Article number: 2556 (2025)

Abstract

Motor disability is a critical impairment in stroke patients. Rehabilitation has a limited effect on recovery; but there is no medical therapy for post-stroke recovery. The biological mechanisms of rehabilitation in the brain remain unknown. Here, using a photothrombotic stroke model in male mice, we demonstrate that rehabilitation after stroke selectively enhances synapse formation in presynaptic parvalbumin interneurons and postsynaptic neurons in the rostral forelimb motor area with axonal projections to the caudal forelimb motor area where stroke was induced (stroke-projecting neuron). Rehabilitation improves motor performance and neuronal functional connectivity, while inhibition of stroke-projecting neurons diminishes motor recovery. Stroke-projecting neurons show decreased dendritic spine density, reduced external synaptic inputs, and a lower proportion of parvalbumin synapse in the total GABAergic input. Parvalbumin interneurons regulate neuronal functional connectivity, and their activation during training is necessary for recovery. Furthermore, gamma oscillation, a parvalbumin-regulated rhythm, is increased with rehabilitation-induced recovery in animals after stroke and stroke patients. Pharmacological enhancement of parvalbumin interneuron function improves motor recovery after stroke, reproducing rehabilitation recovery. These findings identify brain circuits that mediate rehabilitation-recovery and the possibility for rational selection of pharmacological agents to deliver the first molecular-rehabilitation therapeutic.

Introduction

Stroke is the leading cause of adult disability, with no approved medical therapy that promotes recovery. 70% to 80% of people who sustain a stroke have upper extremity impairment1, and many of them do not regain functional use of the paretic arm, which can lead to difficulties in activities of daily living (ADLs) and engagement in community life2. Unlike much of modern medicine, such as in cancer, immune or cardiac disease, there is no medicine for stroke recovery. Neurorehabilitation has the potential to improve recovery after stroke but in clinical practice has limited effect3. Rehabilitation has limited efficacy due to difficulties in access1,4, intensity5, comorbidities6 and stroke severity7. Advancements in stroke recovery and rehabilitation have overall been modest, as evidenced by the limited effectiveness in large rehabilitation clinical trials8. To address these challenges, a comprehensive understanding of the circuits, physiology, and molecular systems that underly stroke rehabilitation is crucial9.

Stroke recovery depends on the experience or surrounding environment during recovery. Heightened perceptive stimuli, motor engagement, and social interaction promote functional recovery10. Rehabilitation is a therapy that enhances such restorative experiences through repetitive exposure to a stimulus, execution of motor training, and an enriched environment10. Stroke recovery and rehabilitation may improve outcomes through cellular mechanisms of neuroplasticity and over specific time points. Recovery after stroke is most robust in the weeks to months after the infarct, a period in which neurorehabilitative therapy is most effective11. Intensive task-specific training, such as repetitively using the affected forelimb, enhances recovery in human stroke and rodent stroke models during this period11,12. Task-specific neurorehabilitative training enhances synaptic plasticity in cortical neurons near the stroke site13,14 and in corticospinal neurons near the stroke site that project to limb control areas of the spinal cord15. Previous studies have shown that spontaneous recovery after stroke occurs by employing biological and molecular mechanisms in the memory/learning system16. Motor rehabilitation is a re-learning process of acquired motor skills before the stroke. Thus, a molecular mechanism in motor learning might drive rehabilitation-induced motor recovery. A better understanding of the circuits and molecular mechanisms in rehabilitation could enable the development of molecular rehabilitation therapies. Such therapies would specifically activate neuronal circuits or molecules involved in rehabilitation-induced recovery, allowing a drug to mimic the effects of rehabilitation and reproduce functional recovery.

Motor learning and stroke recovery progress through excitatory and inhibitory network changes that influence synaptic plasticity17,18. Post-stroke plasticity changes are critically modulated by excitatory/inhibitory balance in the remaining neuronal circuits. Elevated excitatory activity, triggered by the blockade of inhibitory signals, enhances plasticity and facilitates functional recovery after stroke19,20,21. These findings suggest that the higher the excitatory signal relative to the inhibitory signal, the better recovery. However, this concept might be oversimplified because synaptic connections and circuits formed by excitatory and inhibitory neurons exhibit notable complexity22,23. A recent study has also shown that inhibition of a specific interneuron subpopulation (VIP interneurons) enhances recovery after stroke, presumably through a disinhibition circuit mechanism24. Motor control is achieved by coordinated neuronal activity in many distinct neuronal populations25,26. In the normal brain, neuronal activity patterns are fine-tuned through a motor learning process mediated by synaptic plasticity27. Stroke causes disconnection of neural networks in adjacent and distant brain regions and disorganizes neuronal activity patterns necessary for motor control in a physiological state28,29.

GABAergic inhibitory neuron diversity is necessitated by functional versatility in shaping the spatiotemporal dynamics of neural circuit operation22, and fine-tuning of specific inhibitory circuits is required for efficient learning processes30,31. For example, motor skill learning with lever press tasks causes a decrease in the number of synapse terminals formed by somatostatin interneurons and increases those formed by parvalbumin interneurons30. These findings suggest that distinct changes in inhibitory circuitry among different interneuron subtypes may be crucial for facilitating functional recovery following stroke, particularly in tasks involving highly skilled movements. However, the distributed brain circuits that mediate neurorehabilitation-induced recovery after stroke have not been defined, their causal role in this process, and whether a specific pharmacological therapy for stroke recovery might be developed from these phenomena has not been assessed. Here, we show that neuronal circuits formed by presynaptic parvalbumin interneurons and stroke-projecting neurons mediate neurorehabilitation-induced recovery through network synchronization which provide molecular drug targets reproducing rehabilitation effects.

Results

Post stroke rehabilitation improves motor performance

To understand the neuronal circuit underlying functional recovery induced by rehabilitation, we developed a rehabilitation paradigm in the mouse that engages repetitive, skilled forelimb use by the affected limb, imitating rehabilitation for human stroke patients12,32 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). Such rehabilitation enables intense reach-to-grasp training ( > 800 reaches/day). We tested the effect of this rehabilitation paradigm on functional recovery after stroke in primary motor cortex (M1, caudal forelimb area, CFA, Supplementary Fig. 2) using two motor tests, the skilled forelimb reaching test and the grid walk test, which assess motor performance in reach-to-grasp behavior and innate walking precision, (Fig. 1b). We found that stroke significantly decreased the success rate of skilled reaching (Fig. 1c) and diminished gait function (Fig. 1d). Skilled reach rehabilitation completely recovers the motor performance in the skilled reaching task (Fig. 1c, e) and also improved functional recovery in gait (grid walk) (Fig. 1d,f), indicating that intensive rehabilitative therapy promotes motor recovery at or near non-stroke motor performance.

a Rehabilitation box used in the study. Mice stably engage in reach-to-grasp training for 3 weeks, 5 days a week during recovery. n = 12. The error bars are smaller than the symbols. b Timeline of rehabilitation and behavioral testing. The blue triangles indicate behavioral tests. Pretraining for behavior tests and rehabilitation periods are indicated as blue and red rectangles. c, d Skilled reaching test (c): success rate (time by group, F (6, 64) = 10.35, P < 0.0001) and grid walk test (d): foot fault rate (time by group, F (6, 64) = 26.49, P < 0.0001). Two-way repeated measure ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. e, f Functional improvement in the recovery period in the skilled reaching test (e) and the grid walk test (f). Two-tailed paired t-test. (a–f) n = 8 (Sham), 8 (Sham + Rehab), 10 (Stroke) or 9 (Stroke + Rehab). (b) Created in BioRender127.

Motor recovery after stroke is associated with plasticity in brain areas anatomically connected to the stroke site. The ipsilesional premotor cortex and the isotopic area to the stroke site in the contralesional hemisphere are regions well-known for contributing to motor recovery33,34. To identify the brain area most important to motor recovery, we tested the functional significance of the rostral forelimb area (RFA) within ipsilesional premotor cortex and the contralesional CFA by inducing a second stroke in these sites after successful rehabilitation (Supplementary Fig. 3a). A second stroke in ipsilesional RFA eliminated rehabilitation-induced behavioral gains in both tasks, while a contralesional stroke did not cause significant changes (Supplementary Fig. 3b, e). These results indicate that intracortical circuits in RFA (premotor cortex) are a site of rehabilitation-induced recovery.

Post stroke rehabilitation restores functional connectivity in specific circuits

Execution of precise motor tasks requires neuronal population activity in the motor and premotor cortex35,36. Stroke causes not only neuronal death in the infarct core but also cortical network uncoupling characterized by less synchronized firing activity. This uncoupling, quantified as decreased functional connectivity, is closely associated with behavioral deficits28,37,38. We assessed neuronal activity and functional connectivity in the main neurons with intracortical connections (layer 2/3 neurons) in the RFA, employing a two-photon microscope equipped with a rotating grid wheel (Fig. 2a, b). Previous studies demonstrated that walking behavior on a rotating grid sensitively detects motor deficits and network uncoupling after a stroke28,39. Rehabilitation-induced stroke recovery is present in both skilled reach and grid-walking tests. However, the rehabilitation activity in these studies is repetitive skilled reach. Using the same behavioral paradigm for training and assessment could introduce confounding factors, as post-stroke training can lead to compensatory movements that affect outcomes40,41,42. Therefore, we selected the grid walk paradigm over the reaching task for the calcium imaging studies. Stroke reduced the number of active neurons, calcium transient frequency, connection number, and connection density in these neurons, though they are distant from the infarct (Fig. 2c–f, the distance from the infarct to the center of the imaging field is 925 ± 25 µm. n = 6). This reduction signifies a deterioration in neuronal activity and functional connectivity. While the number of active neurons spontaneously increased over time, both the frequency and connection density remained depressed 28 days post-stroke (Fig. 2d, f). Rehabilitation yielded a significant increase in the number of active neurons and functional connections. Rehabilitated animals showed no significant decrease in frequency or connection density compared to sham animals. To further characterize the functional connectivity changes, we calculated the connection probability of a single neuron as the ratio of functional connections to the theoretical maximum connection number in the population. We found that rehabilitation reduced the fraction of neurons exhibiting sparse connectivity in RFA and increased the neurons with higher connection probability compared to non-treated stroke animals (Fig. 2g). These results suggest that rehabilitation enhances functional connectivity in severely affected neurons. Our data also revealed a significant correlation between connection density and motor performance in the grid waking (Fig. 2i).

a Timeline of calcium imaging study. The green triangles indicate calcium imaging sessions. b Representative trace of calcium transient obtained from active (upper) and inactive (lower) neurons. c Active neuron number (time by group, F (4, 28) = 5.504, P = 0.0021). d calcium transient event frequency (time by group, F (4, 28) = 3.850, P = 0.0129), e functional connection number (time by group, F (4, 28) = 8.518, P = 0.0001). f connection density (time by group, F (4, 26) = 2.936, P = 0.0397). Mixed-effects model, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001: Sham (n = 4) vs Stroke (n = 7), # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, ### P < 0.001: Sham vs Stroke + Rehab (n = 6), + P < 0.05, ++ P < 0.01: Stroke vs Stroke + Rehab, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Two-sided. Tukey’s HSD correction for multiple comparison. g Fractional distribution of connection probability in individual neurons. Red, blue, and black areas indicate the ranges where the fraction increases in stroke, stroke + rehab, and sham groups. Two-way ANOVA (F (26, 196) = 3.789, P < 0.0001), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001: Sham vs Stroke, # P < 0.05: Sham vs Stroke + Rehab, + P < 0.05, ++ P < 0.01: Stroke vs Stroke + Rehab, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (c–g) n = 4 (Sham), 7 (Stroke) or 6 (Stroke + Rehab). h Representative connection maps 28 days after the stroke. Scale bar, 100 μm. i Correlation between motor performance in the grid walking and the connection density. Pearson correlation (n = 49, r = 0.671, P < 0.0001). Two-sided. Data are presented as means ± sem. (a) Created in BioRender127.

Post stroke rehabilitation restores synaptic inputs to stroke-projecting neurons

The significant neuronal activity and functional connectivity changes after post-stroke rehabilitation suggest synaptic alterations in the RFA as a direct effect of stroke, and as a substrate for rehabilitation. We next investigated whether anatomical connectivity also changes in the RFA with rehabilitation. In both healthy and stroke animals, skilled reach training induces formation of new dendritic spines that serve as the primary sites of synaptic connections14,43. We measured dendritic spine density in the RFA and further identified the source of synaptic inputs by monosynaptic rabies virus tracing. Using an intersectional virus approach, we targeted two types of cortical projection neurons implicated in motor control after stroke: corticospinal neurons (Supplementary Fig. 4a) and stroke-projecting neurons (Fig. 3a, b). Corticospinal neurons represent the direct cortical outputs to the spinal cord and play a pivotal role in motor control44; the integrity of the corticospinal tract is a strong predictor of stroke outcomes45. Conversely, stroke-projecting neurons are defined by their axonal projection to the stroke site, detected by retrograde labeling from the future stroke site (retrograde AAV injection onto the CFA before the stroke in this study). Stroke-projecting neurons lose their projection target and receive retrograde injury signals, which impact neuronal excitability, morphology, and gene expression46, and may also possess unique plasticity. Before conducting synaptic measurements, we labeled these neuron types by injecting retrograde AAV expressing GFP and tdTomato into the M1 and the cervical spinal cord (C7) to determine whether corticospinal neurons and stroke-projecting neurons (M1-projecting neurons) are distinct. We found that whereas both neuron types were predominantly localized in layer 5 in the RFA, these neurons were rarely co-labeled (Supplementary Fig. 4b), suggesting corticospinal and stroke-projecting neurons are anatomically distinct. Then, we confirmed the specificity of the rabies virus labeling by injecting helper AAVs and rabies virus in the absence of Cre. We found that the rabies virus causes little leak and labeling in the injection site and no label in the distance brain areas without Cre, indicating minimum leakage by non-specific labeling (Supplementary Fig. 5). In dendritic spine analysis, we observed that neither stroke or rehabilitation affected dendritic spine density in corticospinal neurons in the RFA (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d). In corticospinal neurons, rabies tracing showed decreased synaptic inputs from the CFA (near the stroke site) and the somatosensory cortex; rehabilitation did not cause significant changes in any synaptic input sources (Supplementary Fig. 4e–g). In contrast, stroke-projecting neurons lost a substantial proportion of dendritic spines after stroke in both layers 2/3 and 5 (Fig. 3c–e and Supplementary Fig. 6). Monosynaptic tracing revealed that synaptic inputs were lost in major brain areas projecting to the stroke-projecting neurons (Fig. 3f–h and Supplementary Fig. 7). Rehabilitation restored dendritic spine density and a portion of synaptic inputs to the stroke-projecting neurons from some brain areas including the contralesional RFA, peri-infarct CFA, and thalamus. (Fig. 3d–h and Supplementary Figs. 6, 7). These data identify stroke-projecting neurons in the RFA as a population uniquely affected by loss of synaptic inputs after stroke and uniquely responsive in their input connections to rehabilitation, in a brain region integral to rehabilitation-induced recovery.

a Approach for synaptic inputs in stroke-projecting neurons. b Timeline, virus vectors, and virus injection locations in dendritic spine analysis (upper) and monosynaptic tracing (lower). The dashed lines in the brain illustration indicate future stroke sites (CFA). c Representative images showing dendritic spines (upper: scale bar 5 μm) and G-deleted rabies virus (RVdG) labeled cells (middle and lower: scale bar 1 mm). cRFA: contralesional rostral forelimb area, iRFA: ipsilesional RFA, TH: thalamus, SS: somatosensory area. d, e Spine density in layer 5 stroke-projecting neurons; basal dendrite (d), n = 19 (Sham), 20 (Sham + Rehab), 27 (Stroke) or 22 (Stroke + Rehab), apical dendrite (e), n = 15 (Sham), 15 (Sham + Rehab), 22 (Stroke) or 16 (Stroke + Rehab). Kruskal-Wallis test. 4–5 animals per group. f–h The number of RVdG-labeled cells normalized by the starter cells in the whole brain (f), RVdG injection neighbor: RFA (g), and distant brain areas (h). ORB: orbital area, CFA: caudal forelimb area, SS: somatosensory area, CLA: claustrum, AC: anterior cingulate area, CNU: cerebrum nuclei (striatum and pallidum), TH: thalamus. Kruskal-Wallis test. n = 9 (Sham), 8 (Sham + Rehab), 9 (Stroke) or 11 (Stroke + Rehab). (a, b) Created in BioRender127.

Stroke-projecting neurons mediate motor performance

The restoration of synaptic inputs to stroke-projection neurons after rehabilitation suggests a functional role in motor recovery. To determine if stroke-projecting neurons are causally involved in rehabilitation-induced recovery, we manipulated the stroke-projecting neurons with designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDs) after rehabilitation (Fig. 4a, b). The inhibitory DREADD receptor, hM4D(Gi) or mCherry as a non-DREADD control were virally transfected in stroke-projecting neurons in the ipsilesional RFA before the stroke (Fig. 4a). Immunohistochemical analysis (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 8) revealed that virus expression co-localized with a cortical projecting neuron marker, Satb2 (86.1 ± 1.5%), while showing rare co-localization with an interneuronal marker, parvalbumin (0.38 ± 0.08%). Parvalbumin (PV) interneurons primarily form local cortical connections, indicating effective retrograde labeling without diffusive viral infection. The layer distribution analysis revealed that 30.4 ± 1.3% and 61.1 ± 1.5% of stroke-projecting neurons localized in layers 2–3 and 5, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 8). We also found that their axons densely projected to the contralateral cortex, striatum, thalamus, and cerebral peduncle, but the peri-infarct projection was sparse, indicating thorough destruction of the axonal projection to the CFA and limited axon regeneration (Supplementary Fig. 8). We assessed motor recovery 28 days after stroke and tested stroke-projecting neuron inhibition 3 days later. We assessed motor performance 15 min after the injection of the chemogenetic ligand, clozapine N‐oxide (CNO). Whereas neither hM4D(Gi) or mCherry expression affects baseline motor performance or recovery (Fig. 4c, d: Pre, 7d and 28d), chemogenetic inhibition of stroke-projecting neurons significantly deteriorates motor performance in sham control and rehabilitation-stroke animals in the skilled reaching test (Fig. 4c, e: +CNO). Chemogenetic inhibition also affects the motor performance of the rehabilitation-treated animals in the grid walk test (Fig. 4d, f). These results indicate that stroke-projecting neurons in rehabilitation animals play a significant role in motor recovery.

a Timeline, virus vectors, and injection sites in the chemogenetic inhibition targeting stroke-projecting neurons. b Representative images of the stroke-projecting neurons with hM4D(Gi)-mCherry in the RFA layer 5. The stroke-projecting neurons express a cortical projection neuron marker, Satb2 (right), but not PV (left). scale bar 50 μm. Similar staining was confirmed in the sections from 9 mice. See supplemental material for the quantification. c, d Motor performance in the skilled reaching test (c time by group, F (15, 204) = 9.930, P < 0.0001) and the grid walk test (d time by group, F (15, 204) = 17.86, P < 0.0001). Two-way repeated measure ANOVA, Sidak’s multiple comparison test. e, f Motor performance changes induced by the chemogenetic inhibition in the skilled reaching test (e) and the grid walk test (f). Two-tailed paired t-test. (c–f) n = 11 (Sham/mCherry), 11 (Sham/hM4D), 12 (Stroke/mCherry), 13 (Stroke/hM4D), 13 (Stroke+Rehab/mCherry) or 14 (Stroke+Rehab/hM4D) Data are presented as means ± sem. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. (a) Created in BioRender127.

Rehabilitation selectively enhances synapse formation from parvalbumin interneurons to stroke-projecting neurons

Temporal patterns of neuronal activity are regulated by both local cortical dynamics and external inputs from distant areas. In addition to external inputs to stroke-projecting neurons, local connections in inhibitory neurons may mediate circuit connectivity and dynamics through mechanisms of synaptic plasticity47. Thus, we next examined the composition of local inhibitory synaptic inputs to stroke-projecting neurons by immunohistochemical labeling combined with monosynaptic rabies tracing (Fig. 5a). We found that rehabilitation significantly increased synaptic input from PV interneurons to stroke-projecting neurons (Fig. 5b, c), but not from the other major classes of inhibitory neurons: somatostatin, or 5HT3a interneurons (Fig. 5d, e). Unlike stroke-projecting neurons, this selective synaptic change was not observed in corticospinal neurons after stroke (Supplementary Fig. 4h–j). Importantly, the density of cortical interneurons did not change by stroke or rehabilitation (Supplementary Fig. 9a–e), and increased PV interneuron inputs were not correlated with PV interneuron density (Supplementary Fig. 9f). Because rabies virus labeling could be affected by virus toxicity and neuronal activity, we confirmed the rehabilitation-induced PV synapse formation using a synapse-specific labeling technique, GFP Reconstitution Across Synaptic Partner48 (GRASP: Fig. 5f-i and Supplementary Fig. 10). GRASP utilizes split GFP, with pre- and post-synaptic components (pre- and post-GRASP), which emit a green fluorescent signal exclusively when expressed at both pre- and post-synaptic terminals. To specifically detect synapses formed by presynaptic PV interneuron and postsynaptic stroke-projecting neuron, we induced presynaptic GRASP in PV interneurons using the PV interneuron-specific enhancer, S5E249 (PV specificity: 91.3 ± 1.64%) and postsynaptic GRASP in the stroke-projecting neurons using retrograde AAV-Cre vector. Consistent with the findings of the monosynaptic tracing study, we noted a marked increase in PV synapses on stroke-projecting neurons in stroke animals treated with rehabilitation (Fig. 5j, k, and Supplementary Fig. 10e). This increase in PV synapses was not accompanied by changes in total GABAergic synapse inputs (vGAT, Supplementary Fig. 10d). Interestingly, stroke significantly decreased the proportion of PV synapses within the total GABAergic synapse inputs and rehabilitation restored it (Fig. 5l). These data indicate that rehabilitation selectively increases PV interneuron input to stroke-projecting neurons and adjust the composition of GABAergic synapse inputs.

a Schematic illustration of interneuron marker labeling combined with monosynaptic tracing. PV: parvalbumin, SOM: somatostatin, 5HT3a: serotonin receptor 3a. b Representative images of RVdG labeled PV interneurons. The green channel shows the GFP labeled starter cells. Scale bar 50 μm c–e The ratio of PV (c), SOM (d), 5HT3a (e) in total local inputs. Kruskal-Wallis test, n = 6. f Schematic illustration of GRASP labeling of synapse formed by stroke-projecting neuron and PV interneuron. g Timeline, virus vectors, and injection sites in the GRASP study. h, i Representative images of GRASP labeled dendrite (H, scale bar 5 μm) and soma (I, scale bar 10 μm). j Example of reconstruction of dendritic tree and GRASP+vGAT puncta. Scale bar 30 μm. GRASP expression patterns were consistent across the staining sessions and the animals k, l The number of GRASP+vGAT puncta (k) and the proportion of GRASP positive synapse in the total vGAT positive synapse. (l) on the stroke projecting neurons. Kruskal-Wallis test, n = 26 (Sham), 26 (Sham + Rehab), 23 (Stroke) or 24 (Stroke + Rehab). (a, f, g) Created in BioRender127.

Parvalbumin interneurons mediate functional recovery

Given the selective synapse formation from PV interneurons to stroke-projecting neurons in rehabilitation, we tested whether post-stroke rehabilitation would activate this neuronal circuit. To this end, we assessed whether post stroke rehabilitation induces activity-dependent gene expression and plasticity changes in the PV/stroke-projecting neuron circuit in RFA by the detection of immediate early genes Zif268 and FosB, and of perineuronal nets, a determinant of PV neuron plasticity50 (Supplementary Fig. 11a, g). We observed that rehabilitation significantly increased Zif268 expression in both types of neurons (Supplementary Fig. 11c, d) and FosB expression in the stroke-projecting neurons (Supplementary Fig. 11e,f). Rehabilitation also decreased the ratio of PV interneurons surrounded by perineuronal nets (Supplementary Fig. 11i,j). These data indicate activation and enhanced plasticity of these neuronal circuits by rehabilitation.

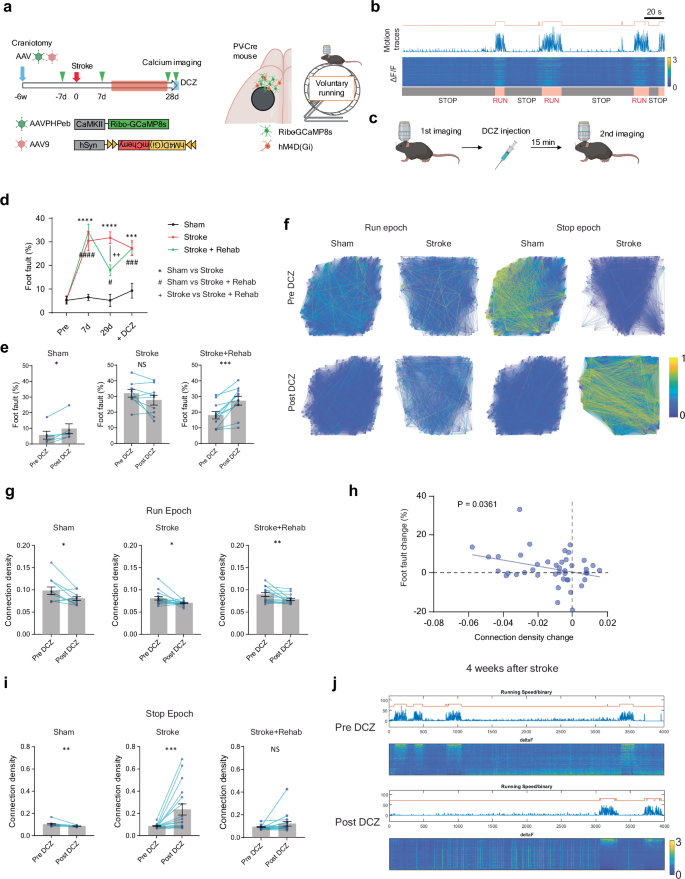

We further tested whether the activation of these neuronal circuits is necessary for functional recovery by rehabilitation. We induced inhibiting hM4D(Gi) or mCherry control in either stroke-projecting neurons or PV interneurons using retrograde AAV-Cre (Supplementary Fig. 12a) and a PV-Cre mouse line (Fig. 6a). We injected the chemogenetic ligand, DCZ, 15 min before every rehabilitation session through the recovery period (Fig. 6b). We validated the efficacy of DREADD inhibition through the treatment period using 2 photon microscope calcium imaging in PV-Cre mice injected with Cre-dependent AAVs expressing hM4D(Gi) and GCaMP8s (Supplementary Fig. 13). We found this DREADD protocol significantly inhibited the movement-induced PV interneuron activation at 10 and 28 days after the stroke (Supplementary Fig. 13). We limited access to the rehabilitation apparatus for 2 h during which DCZ exerts maximum effects51. Compared to the previous studies, this shorter training period decreased the total reaches (millet seed consumption) but remained effective in improving motor performance after stroke (Fig. 6c–e and Supplementary Fig. 12c–e: mCherry). While the inhibition of stroke-projecting neurons influenced rehabilitation-induced motor recovery exclusively in the grid walk task (Supplementary Fig. 12f,g), inhibiting PV interneurons had a significant and broader impact, diminishing the effectiveness of recovery in both skilled reaching and the grid walk (Fig. 6f,g). This indicates that PV interneuron activation has an essential role in rehabilitation-induced recovery in both reach-to-grasp and precision gait function.

a Timeline, virus vectors, and injection sites in the chronic chemogenetic inhibition targeting PV interneurons. b Procedure for rehabilitation with chemogenetic inhibition. c Millet seed consumption with 2-h rehabilitation. n = 6. d, e Motor performance in the skilled reaching test (d time by group, F (6, 68) = 7.887, P < 0.0001) and the grid walk test (e time by group, F (6, 68) = 19.69, P < 0.0001). Two-way repeated measure ANOVA: Stroke + Rehab/mCherry vs Stroke + Rehab/hM4D(Gi), Sidak’s multiple comparison test. f, g Functional recovery by rehabilitation in the skilled reaching test (f) and the grid walk test (g). Two-tailed paired t-test. (d–g) n = 9 (Sham/mCherry), 8 (Sham/hM4D), 10 (Stroke+Rehab/mCherry) or 11 (Stroke+Rehab/hM4D). All data are presented as means ± sem. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (a, b) Created in BioRender127.

Stroke decreases the fraction of fast-rising large amplitude IPSCs, and rehabilitation restores it

Our histological analysis revealed that stroke-projecting neurons undergo structural synaptic alterations following stroke and rehabilitation. To investigate whether these neurons also exhibit changes in synaptic inputs, we conducted patch-clamp recordings of stroke-projecting neurons. We labeled the stroke-projecting neurons with retrograde AAV expressing tdTomato and recorded spontaneous EPSC/IPSC in the tdTomato positive stroke-projecting neurons (CFA-projecting neurons in Sham animals) in the RFA brain slices. We also validated external synaptic inputs by recording evoked EPSCs in response to optogenetic stimulation of thalamocortical axons (Fig. 7a).

a Virus injection and time course for patch-clamp recording. b Representative spontaneous EPSC traces. c, d Frequency (c), and peak amplitude (d) of spontaneous EPSC. Kruskal-Wallis test, n = 11 (Sham), 12 (Stroke), or 13 (Stroke + Rehab). e representative traces of EPSCs evoked by optogenetic stimulation targeting thalamic axons. f, g Response probability (f), and peak amplitudes (g) responding to 50 sequential optogenetic stimulations. Generalized linear mixed model (Fixed effect: Stimulation number; P < 0.0001, Group; P < 0.0001). Two-sided. Tukey’s HSD correction for multiple comparison. n = 11 (Sham), 12 (Stroke), or 13 (Stroke + Rehab). h Representative spontaneous IPSC traces. i, k Frequency (i), and peak amplitude (j) of spontaneous IPSC. Kruskal-Wallis test, n = 12 (Sham), 9 (Stroke), or 10 (Stroke + Rehab). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001,****P < 0.0001. k Distribution of IPSC rise rate and peak amplitude. The red dashed lines indicate the mean peak amplitude and rate of rise of all IPSC events from all recordings. The large amplitude with fast rate of rise events above both mean values (upper right quadrant) amount to 16.5%, 11.7%, and 19.7% of all IPSC events in the Sham, Stroke, and Stroke + Rehab groups, respectively. Chi-squared test; X-squared = 73.4, df = 2, P = 2.2e-16, Bonferroni post hoc test, two-sided; Sham vs Stroke: P < 0.0001, Sham vs Stroke + Rehab: P = 0.0092, Stroke vs Stroke + Rehab; P < 0.0001. Data are presented as means ± sem. (a) Created in BioRender127.

In the EPSC recordings, stroke induced a significant increase in peak EPSC amplitude (Fig. 7d), while EPSC frequency remained unchanged (Fig. 7c). In contrast, rehabilitation significantly increased EPSC frequency compared to stroke animals (Fig. 7c). In optogenetic recordings, stroke reduced the EPSC probability to optogenetic stimulation of thalamic afferents (Fig. 7f) without significant differences in peak amplitude (Fig. 7g), suggesting that excitation of thalamic afferents to the CFA produces less reliable responses in stroke-projecting neurons in both stroke and rehabilitation animals. Our histological data, including dendritic spine analysis and rabies virus tracing (e.g., increased spine density in rehabilitation animals compared to untreated stroke animals and reduced synaptic input from distant brain areas), are primarily consistent with EPSC frequency/probability data but not EPSC amplitude. These findings suggest that EPSC frequency/probability is more closely related to structural synaptic alterations (e.g., synapse loss or formation), whereas EPSC amplitude is influenced by additional factors such as intrinsic excitability, postsynaptic receptor expression, presynaptic vesicle release probability, and phasic/tonic inhibitory inputs mediated by transcriptional regulation. (see Discussion for details).

In the IPSC recordings, we found that stroke increased the IPSC frequency (Fig. 7i) without changing the IPSC peak amplitude (Fig. 7j), indicating increased inhibitory synaptic inputs after stroke. Conversely, rehabilitation showed no significant changes. In the GRASP study, stroke decreases the fraction of PV interneuron synapses without total inhibitory synapse number, and rehabilitation restores these abnormalities. Thus, stroke-projecting neurons may also show fractional changes in IPSCs. We further analyzed the IPSC data to determine whether our IPSC recordings capture PV interneuron functionality. Since PV interneurons target the α1 subunit-containing GABAA receptors, they predominantly generate fast-rising IPSCs52,53,54. Also, the somatic location of PV interneuron inputs results in large-amplitude IPSCs. We have previously shown that the loss of fast-rising large amplitude IPSCs in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease mirrors the functional and physical loss of PV interneurons55. Using as thresholds the mean rate of rise and peak amplitude of all recorded IPSCs, we estimated the fraction of large amplitude fast-rising events in each group, most likely originating from PV interneuron inputs. The data show a reduction in the fraction of large amplitude fast rate of rise IPSCs following stroke, with recovery observed after rehabilitation (Fig. 7k), indicating that stroke reduces, and rehabilitation recovers fractional synaptic inputs from PV interneurons. Additionally, these findings are consistent with the idea that the increased IPSC frequency observed in stroke animals is primarily attributable to small-amplitude or slow-rising inhibitory synaptic inputs from interneurons other than PV interneurons.

Parvalbumin interneurons regulate functional connectivity after stroke

To study how PV interneurons might enhance functional recovery after stroke, we next asked whether PV interneurons could modulate neuronal connectivity associated with motor control. Previous studies had shown that PV interneurons regulate synchronous neuronal activity in the perception of sensory information56,57. To gain insights into the causal role of PV interneurons in motor function, we conducted a chemogenetic inhibition study combined with calcium imaging. The hM4D(Gi) receptor was induced in PV interneurons and neuronal activity was recorded in the excitatory neurons in RFA (Fig. 8a). Given the distinct roles of PV interneurons depending on their activity state56,57, we recorded neuronal activity in both stationary (stop epoch) and active (running epoch) states in voluntary running on a grid wheel (Fig. 8b). Similar to the previous forced running experiment, the stroke animals exhibited severe motor deficits (Fig. 8d) accompanied by a persistent reduction in connection density in both running and stop epochs Supplementary Fig. 14c-j). Four weeks after the stroke, we assessed the effects of inhibiting PV interneurons on motor performance and neuronal activity. We found that inhibition of PV interneurons impaired motor performance during grid running in sham and rehabilitation animals but had no effect on stroke animals (Fig. 8d, e). Notably, inhibition of PV interneurons also decreased functional connectivity during the running epoch in all groups (Fig. 8f, g). Consistent with the correlation between motor function and functional connectivity in the previous calcium imaging (Fig. 2i), the changes in motor performance and functional connectivity showed a significant correlation (Fig. 8h). As expected from the known PV interneuron functions of feedback and feedforward inhibition to excitatory neurons, chemogenetic inhibition of PV interneurons resulted in a significant increase in active neuron count and calcium transient frequency during the stop epoch (Supplementary Fig. 15). Surprisingly, we observed a dramatic increase in functional connectivity during the stop epoch in stroke animals, while sham animals exhibited decreased functional connectivity (Fig. 8i, j). Collectively, these results indicate PV interneuron inhibition decreases the connection density associated with motor impairment in normal animals but induces distinctive effects in stroke animals. This implies that PV interneurons are involved in the regulation of neural network connections, and stroke disrupts circuit control mediated by PV interneurons.

a Timeline, virus vectors, and imaging field for calcium imaging with chemogenetic inhibition. b Representative motion trace and color-mapped calcium transient. The orange line above the motion trace indicates binary detection of the running epoch. c Protocol for calcium imaging and DCZ injection. d Foot fault rate during the calcium imaging. Two-way repeated measure ANOVA, time by group, F (6, 69) = 11.04, P < 0.0001Sidak’s multiple comparison test. e Foot fault rate change by DCZ injection. Two-tailed Wilcoxon test (d, e) n = 6 (Sham), 9 (Stroke) or 11 (Stroke + Rehab). f Examples of connection map before and after DCZ injection in Sham and Stroke groups. g Connection density changes by DCZ injection in the run epoch. Two-tailed Wilcoxon test. n = 11 (Sham), 16 (Stroke) or 15 (Stroke + Rehab). h Correlation between the motor performance change in the grid walking and the connection density change after the DCZ injection. Pearson correlation, two-sided (n = 42, r = 0.324, P = 0.0361). i Connection density changes by DCZ injection in the stop epoch. Two-tailed Wilcoxon test. n = 12 (Sham), 17 (Stroke) or 18 (Stroke + Rehab). j Representative recordings before and after the DCZ injection in stroke animals. c *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Data are presented as means ± sem. (a, b) Created in BioRender127.

Gamma power changes after stroke in the mouse stroke model and human patients

The precise timing of neuronal activity and population synchrony are coordinated by network oscillations58. PV interneurons play a pivotal role as key cellular elements in the generation of such network oscillations, especially gamma waves, which establish oscillatory envelopes of increased neuronal activity onto neuronal networks59. To determine whether neuronal oscillations are associated with stroke recovery, we assessed network oscillation in the premotor cortex/RFA of stroke animals. Recording electrodes were implanted in the RFA, and a transparent acrylic column was placed on the CFA (Fig. 9a), enabling stroke induction without disturbing the implanted electrodes. This setup allows direct comparison of pre-and post-stroke oscillation in the same animals. We recorded the local field potential (LFP) in freely moving mice in their home cage 3 weeks after stroke (Fig. 9a). Stroke causes an immediate global spectral power decrease ranging over delta, theta and gamma frequencies (Supplementary Fig. 16). Recovery of spectral power varied according to the spectral frequency band and the vigilance state. Low gamma power (30–60 Hz) exhibited notable recovery following stroke (Fig. 9b–d), and this was significantly enhanced in animals undergoing rehabilitation (Fig. 9c,d).

a Electrode placement and timeline for the EEG recording. b Representative LFP traces in stroke animals. c Normalized power spectra of network oscillation in ipsilesional premotor cortex in awake period mice 21 days after the stroke (means ± sem). The orange rectangle indicates the lower gamma frequency band. d Normalized spectrum power change in low gamma frequency. Mixed-effects model, time by group, F (10, 62) = 11.87, P < 0.0001. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001: Sham vs Stroke, ++ P < 0.01, ++++ P < 0.0001: Sham vs Stroke + Rehab, ## P < 0.01: Stroke vs Stroke + Rehab, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Two-sided. Tukey’s HSD correction for multiple comparison. n = 4 (Sham), 7 (Stroke) or 5 (Stroke+Rehab). e Illustration of human EEG. f Arm motor Fugl-Meyer (FM) score after stroke. g Correlation matrix of the FM score and the relative gamma power during the recovery period (V3-5) in the ipsi (i) and contralesional (c) motor related areas. M1: primary motor area, PMD: dorsal premotor area, SMA: supplementary motor area in moderate to severe stroke patients (V1 FM < 46). h Correlation between the FM score and the normalized gamma power. Spearman correlation, two-sided (n = 25, r = 0.443, P = 0.026). e Created in BioRender127.

Next, we further assessed the association of gamma waves with functional recovery in human stroke patients. We studied 27 patients with stroke admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF) a median of 12 [8–17] days post-stroke (Visit 1, Supplementary Table 1a). Multiple EEGs were recorded during time in the IRF admission, and an additional EEG was obtained approximately 3 months (86 – 103 days) after stroke onset. The EEG was a 3-min recording taken at rest, and relative low gamma power (30–40 Hz) was analyzed in ipsi (i)- and contralesional (c) hemispheres within five motor regions: M1 (iM1 and cM1), dorsal premotor areas (iPMD and cPMD) and midline supplementary motor area (SMA). 17 patients were available for repeat EEG and functional assessment at Visit 5 (median 92 [86 – 103] days). We found that the arm motor Fugl-Meyer (FM) score significantly improved from Visit 1 to Visit 5 (Fig. 9f: p = 0.0004). At Visit 1, the relative low gamma power did not differ between patients and 27 age-matched healthy control subjects within any of 5 motor regions (Supplementary Table 1b). Subsequently, low gamma oscillations significantly increased in iM1, cM1 and SMA from Visit 1 to Visit 5 (Supplementary Table 1c). Notably, the increase of gamma power in ipsilesional M1 was significantly correlated with the FM scores in moderate to severe stroke patients during the recovery period (V3-5, V1 FM score <46, Fig. 9g, h). Thus, gamma oscillations increase in stroke patients during rehabilitation recovery after stroke, as they do in the mouse. Together, these data support the hypothesis that rehabilitation enhances functional recovery through PV interneuron-mediated mechanisms, and an oscillatory signal of increased neuronal activity by the gamma rhythm.

Activation of PV interneuron improves functional recovery

Finally, we assessed whether there is a pharmacological approach to simulate rehabilitation-induced recovery from stroke, through activation of PV interneuron circuits. To this end, we tested two compounds: AUT00201, a selective positive modulator of Kv3.1 ion channels predominantly found on PV interneurons60 and DDL-920, a selective negative modulator of the γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors with α1β2δ subunits (GABAARδ) responsible for the tonic inhibition of PV interneurons61. The α1β2δ GABAAR is uniquely expressed by PV interneurons as opposed to the α4β2/3δ GABAAR of dentate gyrus granule cells, thalamo-cortical, cortical/hippocampal pyramidal and medium spiny neurons, and the α6β2/3δ GABAAR predominantly expressed by cerebellar granule cells62. Positive modulation of Kv3.1 causes faster activating kinetics and increased firing frequency in fast-spiking GABAergic interneurons63. On the other hand, negative modulation of GABAARδ reduces tonic inhibition and enhances the excitability of PV interneurons64. These alterations in activity subsequently modulate gamma oscillations64,65. We orally administered the drugs, to enhance the applicability of the formulation for potential clinical translation (Fig. 10a). We confirmed that Kv3.1 ion channels and GABAARδ expressed mainly in PV interneurons in both intact and stroke animals (Supplementary Fig. 17). Activation of PV interneurons was tested by single dosing. As expected from the PV interneuron-selective effects of these drugs, both AUT00201 (20 mg/kg66, Supplementary Fig. 18) and DDL-920 (10 mg/kg64, Supplementary Fig. 19) increased the expression of the immediate early gene Zif268 in PV interneurons without changing the density of cells expressing Zif268. Only DDL-920 showed a statistically significant increase (Fig. 10b). In a stroke-recovery study, we started the drug treatment 3 days after the stroke and evaluated the recovery of forelimb motor function with skilled reach (pasta matrix) and gait (grid walk) tests. We did not observe any adverse effects such as weight loss or motor deficits in either sham or stroke animals. Stroke animals treated with the vehicle and AUT00201 exhibited prolonged disability in precisely retrieving pasta pieces (Fig. 10c, d). In contrast, DDL-920 treatment led to a complete recovery of motor function after stroke (Fig. 10c, d). AUT00201 and DDL-920 treatment also produced faster recovery in the grid walk test (Supplementary Fig. 20). These data establish the principle that pharmacological agents can drive beneficial cellular effects seen in rehabilitation-induced stroke recovery and promote behavioral recovery equivalent to that seen in rehabilitation-induced stroke recovery.

a Timeline and procedure for the drug administration of AUT00201 (‘AUT’, 20 mg/kg p.o.) or DLL-920 (‘DDL’, 10 mg/kg p.o.) and behavioral test. b Ratio of Zif268 positive PV interneurons (Left, F (2, 12) = 4.332, P = 0.0383) and density of Zif268 positive cells (right, F (2, 12) = 0.1324, P = 0.8773). One-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 5. c Normalized motor performance in the pasta matrix test. Two-way repeated measure ANOVA, time by group, F (15, 189) = 3.890, P < 0.0001. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01: Sham + vehicle vs Stroke + Vehicle, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01: Sham + vehicle vs Stroke + AUT, ++P < 0.01: Sham + vehicle vs Stroke + DDL, & &P < 0.01: Stroke + vehicle vs Stroke + DDL, Sidak’s multiple comparison test. d Functional recovery from day 3 to day 14. Two-tailed paired t-test for comparisons of 3 d and 14 d. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison for comparisons of functional gains. F (2, 28) = 8.967, P = 0.0010. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001. c, d n = 12 (Sham+Vehicle), 12 (Sham+AUT), 14 (Sham+DDL), 8 (Stroke+Vehicle), 12 (Stroke+AUT), 11 (Stroke+DDL). Data are presented as means ± sem.

Discussion

This study found that motor systems in the brain have a rehabilitation-induced cellular circuit that mediates stroke recovery by selectively increasing synaptic connections between stroke-projecting neurons and PV interneurons in the premotor cortex. Rehabilitation-induced functional recovery relies on neuronal activation in these neuronal populations. Post-stroke motor recovery is associated with increased neuronal connectivity and gamma oscillations, in both mouse models and humans. Both neuronal connectivity and gamma oscillations are regulated by PV interneurons. Collectively, our results indicate that synaptic connections between stroke-projecting neurons and PV interneurons contribute to functional recovery by restoring neuronal synchronization in the ipsilesional premotor cortex. In addition to the regulation of neuronal activity patterns, PV interneurons may also be involved in neuronal plasticity to reorganize neuronal circuits. PV interneurons behave in a manner analogous to their regulation of a developmental critical period in the postnatal brain, with similar alterations in peri-neuronal nets after rehabilitation67. This cellular platform for post-stroke rehabilitation led to the identification of a drug that reproduces the beneficial effects of rehabilitation on behavioral recovery after stroke. A rehabilitation drug could provide substantial benefits in clinical stroke recovery68.

Stroke induces a series of plasticity events at the network, circuit, cellular, and molecular levels. At the molecular level, stroke induces upregulation of growth-promoting gene expressions in parallel with an excitation/inhibition imbalance alteration69. These molecular changes lead to functional and morphological changes in cellular components such as dendrites, axons, and synapses to reconnect the dissociated circuits. These plasticity events are the most prominent in the peri-infarct tissues, but the brain areas anatomically connected to the stroke site also engage in restorative plasticity, especially with therapeutic interventions. For example, corticospinal neurons in the contralesional hemisphere contribute to functional recovery through axonal sprouting from intact to denervated spinal hemi-cord with anti-Nogo-A antibody therapy or optogenetic stimulation33,70. Optogenetic and chemogenetic stimulation targeting a specific neuron type or projection, such as VIP interneurons24 and thalamocortical projection neurons71, can also enhance functional recovery associated with functional and morphological changes in the stimulated neuronal population. These studies raise the concept that restoring weakened connections or activity (e.g., corticospinal axons, thalamocortical axon, VIP responsiveness) promotes functional recovery.

In the current study, we demonstrated that stroke-projecting neurons are involved in functional recovery after a stroke, seemingly through the restoration of synaptic inputs. We observed that rehabilitation significantly increased synaptic inputs from the contralesional hemisphere and also attenuated synaptic input loss from some brain areas, including the peri-infarct CFA and thalamus. Since the reaching task requires neuronal activity in the ipsi- and contralesional motor cortex72 and thalamus26,73, rehabilitation-induced repetitive neuronal activity may restore neuronal connectivity via activity-dependent plasticity. Furthermore, we found that rehabilitation increases synapses formed by PV interneurons and the stroke-projecting neurons, whereas stroke did not significantly reduce the number of the PV synapses or PV interneurons in the RFA. Notably, stroke disturbed the fractional composition of PV interneuron synapses over total GABAergic synapses on the stroke-projecting neurons, and rehabilitation adjusted the fractional disturbance. Additional patch-clamp experiments further validated this finding from a functional perspective. Subtype-selective inhibitory synaptic plasticity occurs in some contexts, such as exposure to a novel environment and motor learning30,31. Furthermore, subtype-selective inhibitory neuron abnormalities have been observed in pathological conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease74 and schizophrenia75. Collectively, these findings suggest that inter-interneuron balance (composition of inhibitory synapse across interneuron subtypes) may impact functional recovery after stroke in addition to excitation/inhibition balance.

As the stroke-projecting neurons lose their synaptic output partner (CFA), forming new synaptic connections with remaining axonal projections or by axonal sprouting might be a reparative response. Stroke-projecting neurons project their axons to the contralateral cortex, striatum, thalamus, cerebral peduncle, and peri-infarct cortex. Our previous research revealed that transcriptional modulation of the memory/learning system, such as CREB overexpression76 and CCR5 knockdown77, increases axonal sprouting to the peri-infarct motor cortex and the contralesional hemisphere. Rehabilitation is a relearning process of previously learned behaviors that may promote similar axonal projections. Anterograde axonal tracing combined with synaptic labeling (e.g., GRASP) and optogenetic validation is warranted for future study.

In addition to structural plasticity after stroke, the current study underscores the notable complexity of synaptic input dynamics. While EPSC frequency analysis showed a marked increase in animals after rehabilitation—aligning with dendritic spine data—we also observed a notable increase in EPSC amplitude, specifically in stroke animals. Moreover, IPSC frequency rose post-stroke, even though the total number of VGAT puncta remained unchanged. Synaptic input frequency and amplitude are influenced not solely by synapse number but also by the functional state of each synapse, shaped by factors such as intrinsic neuronal excitability, presynaptic release probability and postsynaptic modifications, including enhanced receptor sensitivity and upregulation of postsynaptic receptors. Previous stroke research demonstrated that brain ischemia induces AMPA and NMDA receptor clustering78. Stroke also induces robust transcriptional changes, including synaptic protein and neurotransmitter receptors79. Furthermore, stroke-projecting neurons lose their axons at the stroke site. This generates retrograde injury signals that, in turn, initiate extensive transcriptional changes. Prior research has demonstrated that these retrograde injury signals increase vesicle release rates at excitatory synapses46. Given the extensive gene expression changes induced by stroke and retrograde injury signals, complex transcriptomic mechanisms are likely to contribute to the observed alterations in excitatory and inhibitory inputs. Deciphering these mechanisms would benefit from comprehensive and systematic approaches like transcriptomic and proteomic analyses combined with whole-cell/cell-attached patch-clamp recordings, and optical methods for establishing unbiased measurements of membrane voltage.

At the circuit level, our calcium imaging study reveals dynamic shifts in neuronal activity and functional connectivity. Seven days post-stroke, there is a marked reduction in the number of active neurons, activation frequency, connection number, and connection density. During the recovery phase, active neurons and connection numbers spontaneously recover, yet the lowered frequency and connection density remain. Rehabilitation enhances the number of active neurons and connections. Fractional connection density analysis shows that rehabilitation reduces the proportion of neurons with sparse functional connectivity, suggesting that rehabilitation helps restore severely affected neurons. These findings imply that rehabilitation selectively modulates the function of initially inactive and severely affected neurons.

Notably, rehabilitation induced overshoot effects, surpassing physiological levels observed in Sham animals across various experiments (e.g., PV synapse number in histology and active neuron count in calcium imaging). During post-stroke recovery, numerous biological metrics exceed baseline physiological levels in brain tissue, particularly with enhanced plasticity, including axonal projections77, dendritic spine length and turnover80,81, and blood vessel density82. These phenomena reflect two key aspects of stroke biology. First, certain histological and physiological features may indicate enhanced plasticity beyond normal levels, such as increased expression of immediate early genes and decreased expression of perineuronal nets. Since PV interneurons are crucial for synaptic plasticity, their overshoot could signify a transient boost in plasticity, as observed in motor learning30. Second, functional recovery often demands more than the original physiological capacity, as the remaining components of the network must compensate for lost functions. This necessity could explain the overshoot in active neurons and connection numbers observed in our calcium imaging study.

Our EEG data revealed dynamic spectral power changes across broad spectral ranges and different vigilance states. We found that spectral power spontaneously recovers to some degree in most spectral ranges. These changes are probably associated with recovery from early depression of neuronal activity or diaschisis. Additionally, previous studies have identified several factors linked to the reduction of gamma oscillations following stroke, including increased tonic inhibition83, glial activation83,84, and reduced blood flow85. These mechanisms may, therefore, also play a role in the observed effects. Spectral power recovery is incomplete in many state/spectral range combinations. In recordings 21 days after stroke, the stroke animals show significantly lower delta power in all vigilant states. Theta power was also persistently reduced in the NREM/REM, while reduction of low gamma was prominent in the AWAKE state. In the physiological state, theta oscillation is strong in the REM and NREM periods, and low gamma is strong in the AWAKE period. Thus, the reduction of spectral power may persist in the vigilant state in which strong oscillatory activity emerges. Our rehabilitation paradigm induced statistically significant improvement only in the low gamma in the AWAKE period. Accumulating data support the idea that PV interneurons mediate the recovery of low gamma during rehabilitation. Firstly, PV interneurons are considered the major players in generating or regulating the temporal structure of neuronal oscillation, especially gamma oscillation58. PV interneurons are adapted for fast synchronization of network activity, as they resonate at gamma frequencies and exert strong perisomatic inhibition that is capable of precisely controlling spike timing86. Optogenetic studies further evidence the critical role of PV interneurons in gamma oscillation87,88. Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that gamma oscillation plasticity (gamma potentiation) is also mediated by parvalbumin interneurons89. Secondly, motor execution activates gamma oscillation, known as motor gamma oscillation90. The current study demonstrates that rehabilitation induced immediate early gene expression in PV interneurons is concomitant with enhanced gamma oscillation. An in vivo opto-tagging experiment also revealed that skilled reaching evokes PV interneuron activities91. Mouse stroke studies demonstrated that neuronal activation at gamma frequency by light flicker92 (administered 2 h after the stroke, 1 h, twice daily for 14 days) and optogenetic stimulation targeting vGAT-positive interneurons85 (administered 3 to 5 min after the stroke, total 48 min) induced persistent enhancement of gamma oscillation. Although these interventions were early after the stroke, these results suggest that the activation of neuronal circuits at gamma rhythm can induce persistent gamma oscillation enhancement after stroke. Lastly, some rehabilitation-induced PV interneuron changes can impact gamma oscillation. We found that rehabilitation increased synapse formation between the stroke-projecting neurons and the PV interneurons and decreased perineuronal net expression. Lensjo et al. reported that the degradation of perineuronal nets by ChABC increases gamma oscillation concomitant with heightened ocular dominance plasticity93. Although we found PV synapse formation in specific neuronal circuits, the perineuronal net change might impact the plasticity of the entire cortical network. Collectively, it is probable that PV interneurons are involved in the increased gamma oscillation during rehabilitation. We note that our study specifically focuses on the neuronal circuits formed by stroke-projecting neurons and PV interneurons. Therefore, it is highly plausible that other neuronal networks, including circuits involving different interneuron types, also contribute to the observed increase in gamma power during rehabilitation. To fully understand the mechanism by which stroke and rehabilitation alter neuronal oscillations, mechanistic studies such as chemogenetic and optogenetic interventions, together with EEG recordings should be done to systematically and precisely describe the causal links.

In the current study, we investigated PV interneuron function using acute and chronic DREADD inhibition. We should note that different functionalities are affected by the different DREADD protocols. Acute inhibition of PV interneurons directly affects neuronal signal dynamics in the circuit in which PV interneurons regulate functional connectivity. Conversely, chronic inhibition of PV interneurons would influence plasticity changes in the circuit repeatedly activated by rehabilitation. Activity-dependent mechanisms regulate inhibitory synapse plasticity94,95. A recent study also demonstrated that chronic inhibition of PV interneurons abolishes PV bouton formation induced by environmental enrichment in a model of schizophrenia96. Therefore, chronic PV inhibition during rehabilitation is likely to inhibit synapse formation between PV interneuron and stroke-projecting neurons and affect functional connectivity in the circuit.

Two candidate drugs induced distinctive effects depending on the behavior tested. Complete recovery occurred in the pasta matrix test only in the DDL-920-treated animals but not the AUT00201-treated animals. Because immediate early gene expression was significantly upregulated only by DDL-920, improvement of this task may be attributed to the extent of PV interneuron activation. Improvement by DDL-920 was more dramatic in the pasta matrix test, which requires precise reach-to-grasp movement as in our rehabilitation paradigm, compared to the grid walk test. These findings suggest that motor system PV interneuron circuits are responsive to the pattern of motor activity to which they are presented, with reach-to-grasp behavior plasticity greater than that in walking precision. Further studies are warranted to refine dosing and treatment regimen and duration because the effective level of target occupancy achieved during the study may have been sub-optimal for one or both agents based on the once-per-day dosing strategy employed. The potential for these and other targeted pharmacological agents to work in an additive or synergistic fashion to enhance behavioral outcomes will also be important to evaluate. Additionally, further investigation is necessary to identify how these drugs improve functional recovery, including Kv3.1-mediated PV interneuron firing rate changes, GABAARδ-mediated tonic inhibition, and gamma oscillation.

The current study has some limitations regarding the selection of animals used. We conducted the study with young male mice with motor deficits in the skilled reaching behavior. This approach allows rapid discovery experiments of circuit and drug effects. About 80 % of strokes occur in individuals over 6597. Aging is associated with increased stroke prevalence, greater stroke-related mortality, and disability, and older patients are at higher risk of complications related to thrombolytic treatment compared to younger patients97. Aging also affects stroke-related biology, including neuronal cell death98, synaptic plasticity99, and immunological response100,101. Sex differences can also influence stroke outcomes. Several studies reported worse disability and poorer quality of life in female stroke patients102,103, possibly due to different cerebrovascular104 and immune responses105. Therefore, confirming the significance of neuronal circuits formed by stroke-projecting neurons and PV interneurons in different ages and genders is crucial for translating the current findings into clinical settings. We also selected animals with detectable motor disability in the behavior tests because our goal is the development of therapies for severely affected stroke patients who have little chance for satisfactory recovery. Previous studies have demonstrated that recovery from motor impairment is not necessarily correlated to the size of the brain lesion but is better correlated to cortical remapping and axonal sprouting106,107. We identified functional connectivity in the premotor cortex as a strong predictor of functional outcomes. Furthermore, the human EEG study reveals a significant correlation between gamma power increase and motor recovery in patients with moderate to severe motor disability. These findings suggest that local neuronal ensembles in the remaining network might be responsible for motor impairment in severely affected individuals.

Our findings have clinical implications. First, stroke or rehabilitation-induced network changes are heterogeneous, even within a single brain region. The comparisons of corticospinal neurons and stroke-projecting neurons and three main interneuron subtypes support this concept. Identification of precise neuronal circuit mechanisms and cell type-specific drugs may allow selective connectivity modification that activates pro-recovery circuits and inhibits anti-recovery circuits. Second, neuronal synchronization in circuits adjacent to or connected with stroke is associated with functional recovery. Similar strategies have been suggested in other neurological diseases108. These data suggest that establishing an envelope of increased neuronal excitability, with the restoration of gamma oscillations, may facilitate task-specific motor training in promoting neuronal and behavioral recovery after stroke. Finally, our study underscores the potential of drug therapies that replicate the biological processes underlying rehabilitation mechanisms for functional recovery. While rehabilitation is a modestly effective therapy, various obstacles hinder its effectiveness or patient participation. Our rehabilitation paradigm models human rehabilitation. Therefore, the effects of rehabilitation in the study are not as robust as other unphysiological modalities, such as gene knockout or optogenetics, capturing physiological rehabilitation characteristics. These characteristics could be challenging when detecting significant biological events but enable the identification of clinically relevant biological changes in physiological conditions. A deeper understanding of rehabilitation biology holds the promise of developing a medical rehabilitation drug with a more effective treatment for stroke patients experiencing motor disabilities, especially for those unable to engage in quality rehabilitation therapy.

More at link.

No comments:

Post a Comment