Adherence would be 100% if you had EXACT 100% recovery protocols! Are you that blitheringly stupid you don't understand how to motivate survivors?

My conclusion is you don't understand ONE GODDAMN THING ABOUT SURVIVOR MOTIVATION/ADHERENCE, DO YOU? You create EXACT 100% recovery protocols, and your survivor will be motivated to do the millions of reps needed because they are looking forward to 100% recovery. I'd fire all of you for incompetence! GET THERE!

Enhancing long-term adherence in elderly stroke rehabilitation through a digital health approach based on multimodal feedback and personalized intervention

Scientific Reports volume 15, Article number: 14190 (2025)

Abstract

Multimodal digital health technologies aim to improve long-term adherence in stroke patients through personalized feedback and psychological monitoring. However, the interactive effects of physiological and psychological factors on rehabilitation adherence remain unclear. This study evaluates personalized feedback, physiological and psychological factors, and their independent and synergistic effects to optimize rehabilitation adherence in elderly stroke patients. This study was designed as a longitudinal study, with data collected from 180 participants across two central hospitals between March and September 2024. A linear mixed effects model (LMM) was used to analyze the impact of physiological monitoring, psychological monitoring, and personalized feedback mechanisms on long-term patient adherence. Data were gathered through structured questionnaires, resulting in a final sample size of 540 data points. The time effect has a significant positive effect on rehabilitation compliance. The rehabilitation plan completion rate (A1) increases by 1.25 (t = 34.25) and 2.28 units (t = 62.56) in the mid-term follow-up (T2) and long-term follow-up (T3) respectively; the self-reported compliance score (A2) increases by 1.12 (t = 31.39) and 2.3 points (t = 64.27) at T2 and T3 respectively; the completion of specific activities (A3) increases by 1.37 (t = 50.34) and 2.34 units (t = 86.26); the number of interruptions (A4) decreases by 0.89 (t = -17.31) and 2.11 times (t = -41.17) respectively. In personalized feedback, high-quality feedback (D2) significantly promotes compliance (β = 0.0318, t = 2.08), while excessively frequent feedback (D1) showes a negative impact (β=-0.0914, t=-1.93 ). In terms of psychological factors, positive emotion (C3) has a significant positive effect on compliance (β = 0.1572, t = 2.695), while depressed emotion (C1) significantly reduces interruption behavior (β=-0.0885). The interaction effect between physiological factors and psychological factors is not significant, indicating that their influence is relatively independent. This study demonstrates that personalized feedback, psychological support, and time effects are essential for enhancing rehabilitation adherence in elderly stroke patients. High-quality, relevant feedback significantly improves adherence, while ineffective feedback may have adverse effects. Positive emotions within psychological factors promote adherence, whereas depressive emotions hinder recovery, underscoring the importance of psychological support. Although physiological and psychological factors lack significant interactive effects, their independent influences merit attention and optimization in rehabilitation interventions.

Introduction

Stroke, also known as cerebrovascular accident (CVA), is an acute cerebrovascular disease that includes both ischemic (cerebral infarction) and hemorrhagic types1 Stroke poses a huge challenge to global health care systems, with nearly 7 million deaths worldwide, making it the second leading cause of death and the third leading cause of disability2,3,4. From 1990 to 2019, the absolute incidence of stroke increased by 70% and the prevalence increased by 85% worldwide, partly due to population growth and aging5. According to the study of the Global Burden of Disease (GBD), improvements in healthcare technology have led to a decline in stroke mortality4, but an increasing number of people suffer from permanent post-stroke impairments, including motor6, language7, cognitive8 and psychological impairments9. These complications are associated with worse outcomes, reduced treatment compliance10, increased mortality11, and higher healthcare utilization and costs12, placing a greater demand on rehabilitation services. According to statistics, the prevalence of stroke in China and most provinces continued to increase13from 2013 to 2019. The Chinese government advocates actively innovating rehabilitation medical service models, focusing on patients, integrating rehabilitation into the entire process of disease diagnosis and treatment, improving medical outcomes, and promoting rapid rehabilitation and functional recovery of patients14.

Age is a major factor for stroke. The incidence and prevalence of ischemic stroke are higher in the elderly than in younger people15. The incidence of stroke in both men and women more than doubles every year after the age of 55, and 65% of strokes occur in individuals over the age of 65. In research on elderly stroke patients, the impact of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and previous myocardial infarction has been widely recognized16,17. These comorbidities not only increase the physical burden but also have a negative impact on the patients’ mental health. For example, hypertension and diabetes can exacerbate fatigue and mobility limitations, reducing the ability to engage in physical rehabilitation18,19. Psychologically, comorbidities often lead to higher levels of anxiety and depression, which are closely linked to decreased rehabilitation adherence. Previous studies have shown that depression significantly reduces motivation and participation in rehabilitation, often leading to non-compliance with prescribed treatments20,21.In addition, about one-third of stroke patients will experience psychological disorders at some point in the rehabilitation process22, such as depression and anxiety, which will have an adverse effect on rehabilitation compliance and often lead to complications and disability, or even early death23,24. Therefore, special attention should be paid to the specific needs of elderly patients, and personalized intervention programs that are user-centered and meet their physiological and psychological characteristics should be designed to improve rehabilitation compliance and quality of life in this group.

The complexity and long-term nature of the stroke rehabilitation process require patients to maintain a high level of compliance. Digital health technology, with its convenience, efficiency, and personalized customization, provides new possibilities for improving long-term compliance in stroke rehabilitation25. Digital health management basically has three steps, including data monitoring, data processing, and rehabilitation intervention26. Digital health technology plays a key role in each part by using multimodal signal monitoring27. Multimodal monitoring technology refers to the use of multiple sensors and methods to collect and analyze patient data26. These data include electrocardiogram (ECG) data, electroencephalogram (EEG) signals, electromyogram (EMG) signals, blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, skin electrical activity and other physiological signals28, as well as psychological data obtained through questionnaires, behavioral tests, and ecological momentary assessment (EMA)29. Previous studies have demonstrated that physiological monitoring (such as heart rate, blood pressure, physical activity) and psychological monitoring (such as emotional state, anxiety, depression) positively impact rehabilitation and patient compliance30,31,32,33.These studies mainly focus on evaluating the patient’s rehabilitation status by comprehensively analyzing multiple physiological signals26,34,35,36. For example, electroencephalogram (EEG) is combined with electrooculogram (EOG) to more accurately monitor fatigue levels. In addition, there are studies dedicated to emotion recognition technology based on multimodal physiological signals37,38, such as assessing an individual’s mental stress level by analyzing heart and respiratory activity. However, although the independent effects of physiological and psychological monitoring have been studied, there is currently a lack of systematic empirical research on their interactive or synergistic effects on the long-term compliance of stroke patients.

Studies have shown that the use of real-time personalized feedback intervention as a means to improve patient compliance during rehabilitation has been widely recognized39,40,41. However, this process often fails to fully reflect the patient’s overall rehabilitation progress and lacks comprehensive consideration of other influencing factors, such as psychological state, pain perception, and social function. Personalized intervention feedback refers to the process of using the patient’s physiological and psychological information to adjust the rehabilitation treatment plan in real time. At present, dynamic feedback is mainly used in sports rehabilitation42, stroke rehabilitation43, chronic disease management31, etc. Patients can intuitively understand their rehabilitation effects and progress, enhance their sense of self-efficacy44, and gain social support45, thereby increasing their enthusiasm for continuing to participate in rehabilitation training. In stroke rehabilitation, although some studies involve feedback intervention or reminders, such as brain-computer interface (BCI) feedback46, electronic biofeedback47, mirror visual feedback (MVF)48, etc., most studies only focus on the feedback or evaluation of patients during a certain functional rehabilitation process. For example, using electromyogram (EMG) or motion sensor data, dynamic feedback can identify the patient’s motor pattern and force output, and make immediate adjustments when the patient completes certain rehabilitation movements (such as arm lifting and stretching)49. In addition, due to the lack of comprehensive consideration of multi-dimensional feedback, such as effectiveness, relevance and timeliness, patients may adopt incorrect rehabilitation strategies, thereby affecting the rehabilitation effect50. Different patients have different responses and needs for feedback, especially for the elderly, whose physical conditions, cognitive conditions and rehabilitation needs vary greatly16. Feedback information and rehabilitation plans need to better adapt to individual differences, avoid generalization of rehabilitation program information, and achieve personalized intervention51. However, research on using multimodal data to provide personalized feedback and adjust intervention measures in real-time remains limited in the field of stroke rehabilitation, especially the impact on long-term patient compliance.

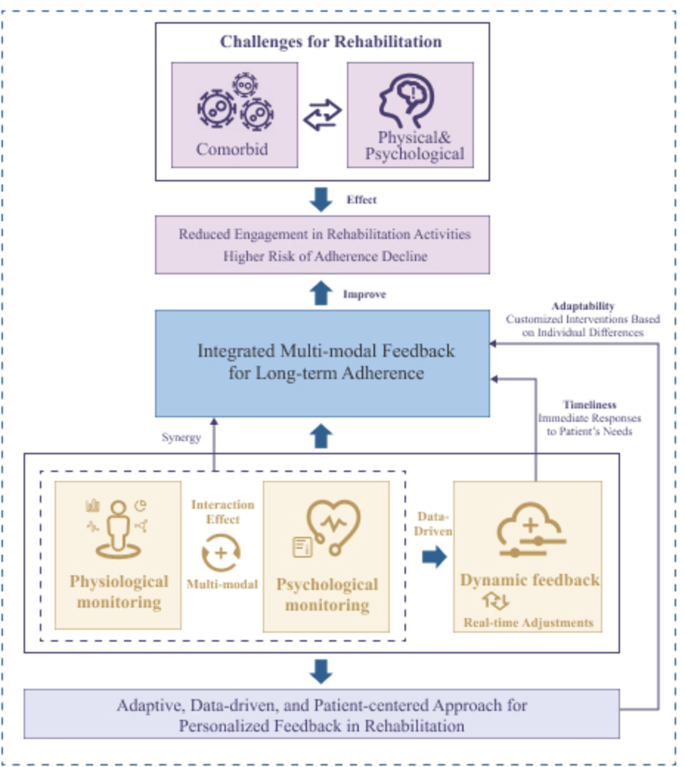

This study aims to explore the impact of a digital health model based on multimodal personalized feedback on the long-term compliance of elderly stroke patients and the effectiveness of personalized feedback intervention strategies. Figure 1 illustrates a framework that outlines the potential interaction between various feedback types (physiological, psychological, and personalized feedback) in enhancing long-term rehabilitation adherence.In this study, we employed a linear mixed-effects model (LMM) to evaluate the impact of various factors on long-term adherence in elderly stroke patients. The LMM is particularly suitable for analyzing longitudinal data, as it allows for the modeling of both fixed and random effects, accounting for the hierarchical structure of the data and the correlation between repeated measurements from the same individual52.

The novelty of this study lies in its comprehensive integration of multimodal feedback mechanisms, real-time intervention adjustments, and long-term tracking of rehabilitation adherence.By incorporating real-time dynamic adjustments in feedback and personalized interventions tailored to the specific needs of elderly patients, this study introduces an innovative approach to enhancing adherence, which has not been fully explored in the context of stroke rehabilitation. Additionally, the longitudinal design of the study allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of how multimodal feedback impacts long-term adherence.

Related work

Although existing research has extensively explored the independent effects of physiological and psychological factors on the rehabilitation process, there are still several limitations in the current studies, especially in exploring the interaction between physiological and psychological factors and their synergistic effects on rehabilitation adherence. These limitations mainly manifest in the following aspects:

At the signal analysis level, taking EEG as an example, although EEG signals are widely used for emotion classification, most studies focus only on the analysis of EEG frequency band features (such as β and γ waves), with little integration of these signals with other physiological signals (such as skin conductance, respiration, etc.) for comprehensive analysi53. The DAI-EF dataset includes various signals (such as EEG, skin conductance, respiration, etc.), but most studies still analyze these signals individually, without exploring the interaction between different modal signals54. Furthermore, some multimodal signal processing studies, although employing complex network architectures, often neglect the correlations between different modalities, leading to limitations in the model’s classification ability and generalization capability. This limitation in signal analysis and processing restricts a comprehensive understanding of the interaction between physiological and psychological factors and hinders the realization of truly personalized interventions.

In rehabilitation practice, although personalized feedback interventions have been widely applied in the rehabilitation field, these interventions often fail to adequately reflect the overall progress of the patient’s rehabilitation and lack comprehensive consideration of other influencing factors (such as psychological state, pain perception, and social function). For instance, mindfulness-based interventions and breathing exercises have been shown to have positive effects on short-term rehabilitation, but their impact on long-term adherence has not been sufficiently validated55,56.These research findings further support the synergistic effect between psychological and physiological factors, but they still largely focus on short-term effects, lacking a systematic evaluation of the impact on long-term adherence.

At the theoretical and methodological level, the traditional Cartesian mind-body dualism framework treats psychological and physiological factors as independent entities, lacking an effective theoretical framework to explain their interactions. Although Warren H. Teichner proposed a psychophysiological framework attempting to integrate factors such as the environment, emotional stimuli, and information overload, this framework mainly relies on literature reviews and theoretical derivations, lacking experimental verification. Engel proposed the biopsychosocial model, which emphasizes the impact of psychological and social factors on physical health. However, in multimodal signal analysis, no unified theoretical framework has been established to understand and integrate these interaction effects57.Khan et al. also pointed out that traditional univariate analysis methods have not effectively captured the synergistic effects of physiological and psychological factors in the rehabilitation process58.

Existing literature has made theoretical contributions to the development of adherence in stroke patients, but there are still some limitations: (1) Current research mostly focuses on single-modal signals, with limited exploration of multimodal signal interactions; (2) Existing theories are not yet well-established in integrating physiological and psychological interactions; (3) Most studies focus on short-term interventions, with insufficient consideration of long-term adherence and the dynamics of personalized interventions; (4) Systematic research on long-term adherence and its influencing factors still needs to be strengthened.

Methods

Sample and setting

Setting a moderate effect size, a significance level of 0.05, and a statistical efficacy of 0.80, a sample size of at least 149 participants was calculated to be able to ensure the robustness of the model and the reliability of the analyzed results59. Considering potential participant dropouts, we referred to the 2024 rehabilitation review published by the WHO Rehabilitation Training and Research Collaboration Center (Wuhan), which reports that dropout rates in stroke rehabilitation studies typically range from 10 to 20%. To compensate for potential data loss and ensure statistical power, we adjusted the initially estimated sample size of 149 to a final total of 180 participants. Furthermore, to minimize attrition, we implemented a series of strict follow-up management strategies, including regular reminders, direct communication with participants and their caregivers, and flexible scheduling of follow-up appointments to enhance long-term adherence and maintain data integrity.This study investigated all patients diagnosed with stroke in Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital and Union Hospital of Huazhong University of Science and Technology Tongji Medical College between March 1, 2024 and September 31, 2024, including 94 patients in Jinyintan Hospital and 86 patients in Union Hospital, with a total of 180 elderly stroke patients with three-phase visit data collected, for a total sample size of 540 participants. Three follow-up time points were set up in this study: short-term follow-up (T1) on March 1, 2024, mid-term follow-up (T2) three months later on June 1, 2024, and long-term follow-up (T3) another three months later on September 1, 2024.The three-month follow-up interval was chosen primarily based on prior studies on stroke rehabilitation adherence, which indicate that significant changes in adherence behaviors typically occur within this timeframe60,61. Three months after hospitalization, patients reported high adherence (80-100%) to the discharge prescriptions, and vascular events were fewer compared to patients in the control hospitals (8.4% vs. 22%)62. Additionally, the choice of three-month intervals for follow-up visits is supported by clinical evidence (such as functional recovery curves) and aligns with the neuroplasticity window, adherence management patterns, and complication prevention needs. This follow-up interval is also consistent with the practical recommendations of multidisciplinary guidelines. Therefore, the three-month follow-up interval was chosen to effectively monitor patients’ rehabilitation progress and adherence management.

People aged 65 and above were defined as elderly.A member of the rehabilitation team at each hospital was responsible for directing the rehabilitation of the patients. The inclusion criteria were in accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO), the Chinese National Health Commission (NHC) Guidelines for Stroke Prevention and Control in China, the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) Guidelines for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery (Guidelines for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery) and other official guidance documents49,50. Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 65 years; basic cognitive abilities (e.g., alertness and time and place orientation); ability to understand and communicate in Mandarin; and having received at least three months of rehabilitation since stroke onset. Exclusion criteria included: comorbid cancer or dementia diagnoses; patients requiring treatment through strict medication management or dietary control; and patients with imbalanced rehabilitation due to unstable lifestyles or comorbid multiple chronic conditions. Participant recruitment was performed by the treating physician and the research team to ensure that the screening process was ethical and in accordance with research norms. The questionnaires in this study were administered in a privacy-protected setting, and all data were collected with the authorization of the participants. For participants with lower literacy levels, the researchers provided assistance, including help in reading the questionnaire aloud and recording responses during the data collection process. This support not only ensured that participants fully understood the questions but also minimized potential barriers to engagement, which could otherwise lead to inaccurate or incomplete data.The entire questionnaire took approximately 20–40 min to complete.

Model construction

In this study, LMM was used in order to assess the effect of a multimodal personalized feedback intervention on long-term adherence in elderly stroke patients. The dependent variable was set as long-term adherence (A), which contains four measurement dimensions: rehabilitation program completion rate (A1), self-reported adherence score (A2), completion of specific rehabilitation activities (A3), and number of interruptions and re-engagement (A4). The independent variables consisted of three main categories: physiological monitoring (B), which consisted of heart rate (B1), blood pressure (B2), physical activity (B3), and BMI (B4), psychological monitoring (C), which consisted of depression scores (C1), anxiety scores (C2), positive mood (C3), and stress levels (C4), and personalized feedback interventions (D), which consisted of frequency of feedback (D1), feedback validity scores (D2), and feedback relevance scores (D3), and patient feedback response score (D4). Data were collected at T1, T2, and T3 in order to progressively introduce B, C, and D mechanistic variables and assess the impact of these factors on patient adherence at different time points.we have detailed their measurement tools, and scoring criteria in the Table 1 below.

Modeling steps and data analysis

This study used Rstudio 2023.03.0 for data analysis to explore the effects of physical monitoring, psychological monitoring, and personalized feedback mechanisms on long-term adherence in stroke patients through linear mixed-effects modeling (LMM).

To address missing data, median imputation was used for numeric variables, replacing missing values with column medians to minimize bias from outliers. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted by comparing results from the imputed dataset with a complete-case analysis (excluding missing data), confirming consistent findings. Proactive follow-up strategies (e.g., reminders, flexible scheduling) were implemented to reduce attrition.The study design included four types of dependent variables for adherence, and three separate models were constructed for each dependent variable, for a total of 12 models. Model 1 set time points as fixed effects and individual differences as random effects to observe time effects; Model 2 added B, C, and D progressively on this basis to assess the main effects of each variable; and Model 3 added the interaction terms of B and C (B2 × C1, B1 × C2, and B3 × C3) to detect the synergistic effects of physical and psychological monitoring. Model residual diagnostics included VIF to detect multicollinearity, SW test to assess residual normality, and heteroskedasticity test to verify the isotropy of residuals. In addition, the validation of model fit was aided by fixed-effects plots, Q-Q plots, histograms of residuals, and residual distribution plots. The final results were reported by standardized regression coefficients (β), F-values, and goodness-of-fit indices such as AIC/BIC, with the significance level set at p < 0.05. Meanwhile, the cumulative effect and trend change of adherence at different time intervals and with each combination of variables were assessed by comparing the model’s fixed and random effect estimates to reveal the effect of the multimodal personalized feedback interventions at different stages.

Ethical considerations

The objectives and methods were explained to the participants before the start of this study. The questionnaire was anonymous and the information was kept confidential. Subjects had the option to terminate the questionnaire and withdraw from the study at any time, and their participation did not affect the patient’s right to receive treatment. Data were collected only after receipt of a complete consent form.

Results

Descriptive analysis

A total of 180 elderly stroke patients participated in this study. Key demographic information such as age distribution, gender, comorbidities, and physical activity levels are presented. Notably, the majority of patients had hypertension, with a significant number reporting low physical activity levels. Descriptive statistics for all variables are summarized in Table 2.The age distribution of elderly stroke patients was as follows: 45 participants (25%) aged 65–69 years, 54 participants (30%) aged 70–74 years, 46 participants (25.6%) aged 75–79 years, and 35 participants (19.4%) aged 80–85 years. Regarding gender, the cohort included 96 females (53.3%) and 84 males (46.7%). Comorbidity analysis showed that 40 participants (22.2%) had no comorbidities, 65 participants (36.1%) had one, 55 participants (30.6%) had two, and 20 participants (11.1%) had three or more comorbidities. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (140 participants, 77.8%), diabetes (65 participants, 36.1%), and coronary heart disease (45 participants, 25%).In terms of physical activity, 60 participants (33.3%) reported no regular exercise, 45 participants (25%) exercised 1–2 times per week, 35 participants (19.4%) exercised 3–4 times per week, and 40 participants (22.2%) exercised five or more times weekly.

First, the collected data are pre-processed to ensure that their quality is suitable for analysis. This involved dealing with erroneous values, outlier detection and variable transformation. Of note, persistent changes such as blood pressure were categorized into systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), while time points were converted into factors for categorical modeling. In addition, data were standardized to a normalized distribution and prepared for subsequent analysis of results. .

Adherence modeling based on time effects

The effect of time on long-term adherence was significant for all four adherence dimensions (A1, A2, A3, A4). Time points showed gradual improvement in adherence, with the largest improvements observed at T3. The effects of physiological and psychological factors, as well as personalized feedback interventions, were also explored.

Set A1, A2, A3, and A4 as dependent variables, respectively, and introduced time as a fixed effect and a random effect (individual differences) into the model. Setting up A1 rehabilitation program completion rate as the dependent variable, the time point was introduced as a fixed effect and random effect to explain the individual differences of patients. Based on the data analysis, the results of modeling A1 are as follows:

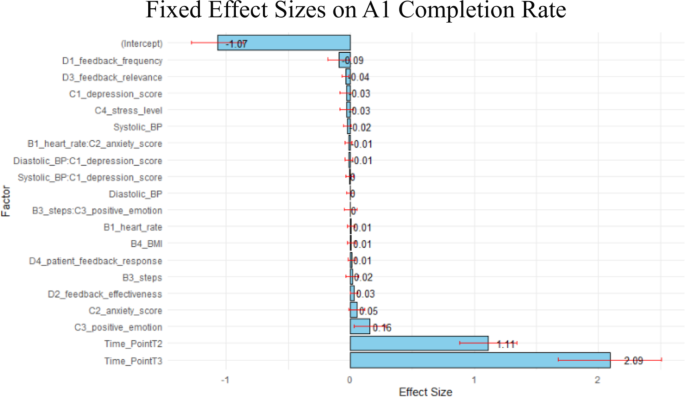

\({\beta _0}\) is a constant term, \({\beta _1}\)is the slope coefficient at the point in time, which indicates the effect of the point in time on the rate of completion of the rehabilitation program, \({b_{0j}}\)is the random intercept term for patient ID, which indicates the deviation of each patient relative to the overall average, and \({\varepsilon _{ij}}\)is the error term. Figure 2 demonstrates the fixed effect sizes of the factors in the A1 model. It can be seen that different factors affect the completion rate of the rehabilitation program to different degrees. The time effect is significant in it, especially in the T2 and T3 stages, which means that the completion rate of patients’ rehabilitation program increases significantly with the passage of time; the effect of T2 and T3 reaches 1.11 and 2.09 respectively, which shows the trend of gradual improvement. Among the personalized feedback intervention variables, D1 and D3 showed some negative effects, albeit not to a strong extent, suggesting that inappropriate feedback frequency and irrelevant feedback content may have a slightly negative effect on the rehabilitation completion rate. D2, on the other hand, showed a small positive effect, suggesting that high-quality feedback contributes to completion rates.The B variable effect was small and barely significant, implying that these physiological factors have a more limited contribution to rehabilitation completion rates. Of the psychological factors, C3 had a slight positive effect, suggesting that positive emotions may have contributed to the completion of the rehabilitation program to some extent, but the effect was weak.

The correlations of random effects, fixed effects, and fixed effects are shown in Tables 3, 4 and 5. The tabular data show that for A1, the results indicate that T2 significantly increased the rate of completion of the rehabilitation program compared to T1 at baseline time, by an average of 1.251 units (t = 34.25), whereas T3 showed an even greater increase, by 2.284 units (t = 62.56). For example, the 2.28-unit increase in rehabilitation program completion rate (A1) at T3 indicates that patients completed, on average, 22.8% more of their prescribed activities compared to baseline. This improvement reflects enhanced adherence over time, potentially translating to better functional recovery. Similarly, a 2.30-point rise in self-reported adherence (A2) at T3 suggests sustained patient engagement, while the 2.11-unit reduction in interruptions (A4) highlights fewer lapses in continuity of care.

The random intercept variance for patients was 0.0068 and the standard deviation was 0.0825, which suggests that fluctuations in the rate of completion of the rehabilitation program were small between patients and that individual differences had a limited impact on the overall trend. In addition, the correlation with the intercept for both T2 and T3 was − 0.688, implying that the improvement at subsequent time points may be slightly smaller in patients with higher baseline levels. In terms of A2, self-reported adherence scores increased by 1.123 points from baseline in T2 (t = 31.39), while T3 increased further to 2.3 points (t = 64.27), demonstrating the significant role of the time effect in enhancing adherence. The randomized intercept variance between patients was 0.0011 with a standard deviation of 0.0335, further demonstrating the small differences in baseline scores.The correlation between T2 and T3 and the intercept was − 0.704 for both, suggesting that patients with higher baseline adherence showed relatively little improvement at subsequent time points. For A3, the estimate at T2 was 1.368 (t = 50.34) and increased further to 2.344 (t = 86.26) at T3, reflecting the significant boosting effect of the time effect on completion of specific rehabilitation activities. The variance of the random intercept for patients was 0.0075 with a standard deviation of 0.0868, suggesting that inter-individual differences in baseline completion were small, and the correlation between T2 and T3 and the intercept was 0.670 for both T2 and T3, which also suggests that patients with higher baseline completion had a relatively small increase in subsequent time points. For A4, T2 significantly reduced the number of interruptions by a mean of 0.887 (t = -17.31), whereas T3 reduced the number of interruptions by 2.109 (t = -41.17), showing a trend toward significantly less interruptive behavior over time. The variance of the randomized intercept for patients was 0.0155 with a standard deviation of 0.1246, suggesting smaller differences in the number of baseline interruptions between patients.This finding was supported by the negative correlation between T2 and T3 and the intercept (-0.685), suggesting that patients with higher baseline interruptions experienced a greater reduction at subsequent time points.

In summary, the time effect demonstrated a significant impact on all four adherence indicators, showing a positive effect of the intervention over time. Although there were some individual differences between patients, the effects were small and the overall trend was more consistent across the sample. In addition, the negative correlation between time point and intercept suggests that patients with higher baseline levels may have relatively smaller gains or decreases at subsequent time points.

Long-term adherence main effect

The analysis of the main effect of time on long-term adherence showed significant improvements in all four adherence dimensions (A1, A2, A3, A4) over time, particularly during T3. Notably, physiological variables did not exhibit significant effects on adherence, whereas psychological factors, such as positive mood, played a more prominent role. Feedback quality (D2) also had a substantial positive impact on adherence, while inappropriate feedback frequency (D1) was associated with a slight negative effect.

In Model 2, the four main adherence dimensions were systematically assessed by progressively introducing B, C, and D. The four dimensions of adherence were assessed in the model. Among these four dimensions, the time effect showed a significant impact, especially on A1 and A3, where patient adherence significantly increased over time.

In the A1 model, the effect of T2 on A1 was 1.0191 (t = 9.52, P < 2e-16), whereas the effect of T3 was 1.9038 (t = 10.92, P < 2e-16), showing that patients’ completion of the rehabilitation program continued to increase over time, and the improvement was particularly significant at T3. With the addition of the B variable, physiological monitoring factors such as B1, SBP, DBP, B3, and B4 did not show a significant effect on A1, indicating that these physiological factors did not play a significant role in this process. Among the psychological factors, C3 had a significant positive effect on A1 with an effect of 0.1572 (t = 2.695, P = 0.00727), whereas the effects of other psychological factors such as C1, C2, and C4 were weaker and did not show a significant effect. With the addition of the D variable, the effect of D1 was − 0.0914 (t= -1.93, P = 0.05433), which was close to being significant, showing that inappropriate feedback frequency may negatively affect the completion of the rehabilitation program, while D2 had a significant positive effect on the completion rate of the rehabilitation program, with an effect of 0.0318 (t = 2.08, P = 0.03814), which further validated the effective importance of feedback.

In the A2 model, the time effects were also significant. the effect of T2 was 1.114 (t = 25.751, P < 2e-16) and the effect of T3 was 2.279 (t = 36.045, P < 2e-16), showing a significant improvement in A2 over time. Among the physiological variables, the effect of B1 on A2 was 0.0212 (t = 1.436, P = 0.1517) non-significant; the effect of SBP was close to significant (P = 0.0722), and the other physiological factors (e.g., DBP, B4, etc.) did not show a significant effect on A2.The effect of time remained significant after the addition of the C variable, with T2 of 1.334 (t = 12.940, P < 2e -16), and T3 was 2.650 (t = 15.802, P < 2e-16). the C variables all had small effects on A2, with C2 approaching significance (P = 0.1204). With the addition of D, the time effects remained significant, with T2 at 1.234 (t = 10.887, P < 2e-16) and T3 at 2.452 (t = 12.570, P < 2e-16). However, the effect of D2 was − 0.0371 (t = -2.510, P = 0.0124), indicating that ineffective feedback may reduce adherence, suggesting that the quality of feedback is more critical than the frequency and relevance of feedback.

In the A3 model, the time effect continued to show a significant positive effect, with an effect of 1.336 (t = 40.345, P < 2e-16) for T2 and 2.280 (t = 46.284, P < 2e-16) for T3, indicating a significant increase in A3 over time.B did not show a significant effect on A3.The effect of C2 (P = 0.1204) was nearly significant, while the other C variables did not significantly affect rehabilitation activity completion. The time effect remained significant with the addition of D, with a T2 of 1.420 (t = 15.809, P < 2e-16) and a T3 of 2.419 (t = 15.600, P < 2e-16). However, the effects of D1 and D2 were not significant, suggesting a smaller effect on A3 completion.

In the A4 model, the time effect continued to show a significant negative effect with a T2 of -0.9325 (t = -14.932, P < 2e-16) and a T3 of -2.2065 (t = -23.922, P < 2e-16), indicating a significant decrease in patients’ A4 over time.The B variables did not show a significant effect on A4.Of the C variables, C1 had a significant negative effect (P = 0.0181), suggesting that patients with higher levels of depression may be less likely to exhibit interruptive behavior. The feedback variable had a smaller effect and did not show significance.

Taken together, the time effect was significant in all adherence dimensions, especially in the completion rate of the rehabilitation program and the completion of specific rehabilitation activities, showing a significant increase in adherence over time; the effects of the physiological variables were generally not significant, suggesting that these indicators have a limited role in long-term adherence; among the psychological variables, positive mood contributed to the increase in the completion rate of the rehabilitation program, whereas depressed mood decreased the number of interruptions, suggesting the the importance of mental health support; feedback effectiveness showed a significant effect in rehabilitation program completion rates and self-reported adherence, suggesting that high-quality feedback helps maintain adherence, while inappropriate feedback frequency may have a negative impact.

Physiological and psychological monitoring interaction effects

The interaction effects between physiological and psychological monitoring factors were explored, but no significant synergistic effects were observed. The findings suggest that the independent effects of physiological and psychological factors are more pronounced in rehabilitation adherence, and more complex mechanisms may be at play.

In terms of psychological monitoring, the results of the study showed that the unique influence of patients’ C3 and C1 in adherence cannot be ignored. In particular, in the A1 model, C3 had a significant positive effect on A1 with an estimated value of 0.1581 (P = 0.0151), which suggests that a positive psychological state 000011 and promotes the rehabilitation process. Positive emotions can increase patients’ sense of commitment and motivation to the rehabilitation task and enhance their willingness to adhere to the rehabilitation program. In the A4 model, C1 showed a significant negative effect on the number of interruptions and re-engagements (estimate − 0.0885, P = 0.0199), suggesting that higher levels of depression may reduce patients’ willingness to re-engage in rehabilitation.

In addition, D had a significant effect on the quality and relevance of the A In the A1 model, the effect of D2 on A1 was significantly positive with an estimated value of 0.0316 (P = 0.0402), suggesting that high-quality, personalized feedback is effective in helping patients to understand the rehabilitation tasks and providing incentives to be more proactive in participating in the rehabilitation program. D3, however, showed a significant negative effect with an estimated value of -0.0385 (P = 0.0121), suggesting that feedback content that is not relevant to the patient’s actual rehabilitation status may negatively affect adherence and weaken the patient’s confidence in the rehabilitation program. Similarly, D2 showed a significant negative effect in the A2 model (estimate − 0.036, P = 0.0149), suggesting that in some cases, ineffective or useless feedback, rather than motivating patients, may play a negative role.

To further explore the synergistic effects between the B and C factors, several physiological and psychological interaction terms (e.g., SBP × C1, B1 × C2, B3 × C3) were included in Model 3. However, from the model results, none of these interaction terms showed significant effects across the adherence dimensions, suggesting that the synergistic effects between physiological and psychological factors are not significant in rehabilitation adherence, or their effects on adherence may be relatively independent. This suggests that perhaps there are more complex mechanisms for the interaction of physiological and psychological factors that are difficult to capture through a simple interaction model. No significant synergistic effects were observed between physiological (B) and psychological (C) factors, suggesting their impacts on adherence are independent. Therefore, future studies may consider using more detailed physiological and psychological measures to explore possible subtle interaction effects.

In summary, the results of Model 3 provide several key insights for enhancing long-term adherence. First, the role of mental health management in the rehabilitation process cannot be ignored, especially interventions to enhance positive mood and reduce depression are crucial; again, the quality of personalized feedback directly impacts patient adherence, and the feedback should be relevant and effective in order to improve patient understanding and confidence in the rehabilitation program. In addition, the synergistic effect between physiological and psychological factors did not show significance, suggesting that the independent effects of physiological and psychological factors should be considered separately in the design of rehabilitation interventions, rather than simply assuming that there is a significant synergistic gain between the two.

Model diagnostics and hypothesis testing variance inflation factor (VIF)

In this section, multicollinearity among predictor variables was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), and the results showed no significant multicollinearity issues. Additionally, robust mixed-effects models were employed to address potential outliers and non-normal residuals. The residual plots and QQ plots demonstrated that the robust model improved the distribution and homoscedasticity of residuals, enhancing the overall model fit.

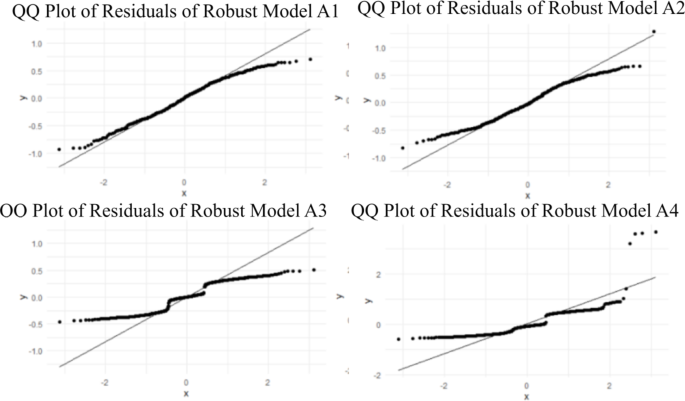

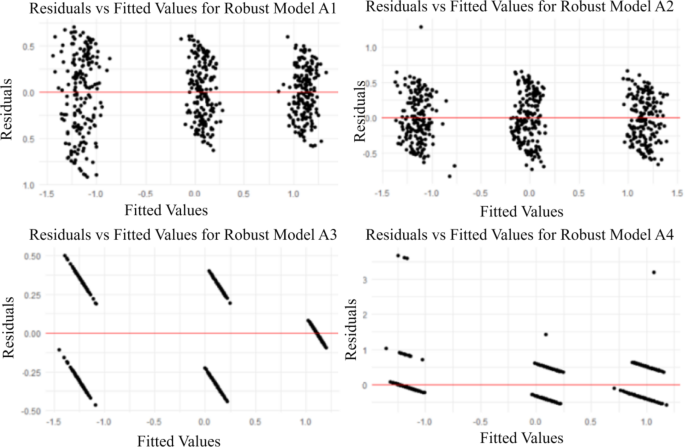

In the multicollinearity analysis, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated for each model (A1, A2, A3, A4) to assess the problem of multicollinearity among the predictor variables. Typically, a VIF value of more than 5 to 10 implies a potential multicollinearity problem, which may distort the coefficient estimates and their significance. In our models, most of the predictor variables have VIF values below 5, which suggests that multicollinearity is not a major problem in these models.VIF values for all models were below 5, indicating minimal multicollinearity. Robust mixed-effects models (robustlmm package) were used to mitigate residual heteroskedasticity and non-normality, improving model reliability. Residual plots (Figs. 3 and 4) confirmed improved homoskedasticity and normality in the robust models.However, we also observe that some of the VIF values are close to this threshold, indicating some degree of correlation between the predictor variables. This finding emphasizes the need for caution when interpreting the coefficients, as multicollinearity can lead to inflated standard errors, which can affect the reliability of the results.

We use robust mixed effects models from the robustlmm package.Robust model aims to reduce the effects of outliers and non-normal residuals in order to estimate coefficients more reliably. The formulation of each robust model is consistent with the structure of the original mixed effects model, while ensuring that the predictor variables are appropriately adjusted to enhance the robustness of the model. These Robust models help to reduce the impact of outliers, thereby improving the overall fit of the model to most of the data.

Residual versus fitted value plots were generated for each Robust model to assess the fit and check for homoskedasticity. The distribution of residuals for the Robust model improved compared to the initial model. While some degree of heteroskedasticity still exists, overall the variance of the residuals stabilizes within the range of fitted values, indicating that the Robust model approach successfully mitigated some of the previous problems, as shown in Fig. 3.

The QQ plot for the Robust model shows an improvement in the normality of the residuals. While there are still some deviations from the diagonal, they are not as significant as in the standard model. This suggests that the Robust model approach may better address the non-normal distribution of the residuals, enhancing the validity of the hypothesis tests associated with the model coefficients, as shown in Fig. 4.The Robust weights show how well the model handles influential data points. Most of the weights close to 1 confirm that most of the observations perform well.

Discussion

This study reveals the profound impact of personalized feedback, psychological factors and time effects on rehabilitation compliance, especially in terms of improvement in the completion rate of rehabilitation plans and the completion of specific activities.Our findings show a significant improvement in rehabilitation compliance at T2 (mid-term follow-up) and T3 (long-term follow-up) compared to baseline (T1). Specifically, the completion rate of rehabilitation programs increased by 1.25 units (t = 34.25) at T2 and by 2.28 units (t = 62.56) at T3, indicating a gradual improvement over time. These results are consistent with previous studies, which suggest that rehabilitation compliance generally improves as patients adapt to rehabilitation activities, leading to the formation of stable behavioral patterns51,52,53,54. However, unlike broad claims in earlier literature, our study emphasizes that significant changes in compliance were observed primarily in the later stages of rehabilitation (T2 and T3), suggesting that the time effect is more nuanced and depends on the patient’s progress in rehabilitation. The continued improvement in compliance observed at T2 and T3 underscores the critical role of sustained support over time in maintaining adherence.

Regarding the role of personalized feedback, research results show that high-quality personalized feedback significantly enhances patients’ participation in rehabilitation and improves compliance. This finding is consistent with Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory(CLT), which states that the frequency and quality of feedback information directly affect the patient’s information processing load. Frequent and excessive feedback, as suggested by CLT, can lead to cognitive overload, which impairs the patient’s ability to process and use the information effectively. In line with this, Burcal et al.71 found that frequent and ineffective feedback can easily cause information overload, leading to patients’ fatigue and loss of enthusiasm for rehabilitation.Particularly, the negative effects of feedback frequency (D1) are evident when feedback is delivered too often, overwhelming the patient with excessive information. In these cases, patients may feel pressured, and their engagement with the rehabilitation process can decrease significantly. Moreover, irrelevant or poorly tailored feedback (D3) can lead to disengagement, as patients are less likely to respond positively to feedback that does not match their current rehabilitation needs or goals. Research shows that lack of pertinence or relevance in feedback can significantly reduce patient compliance, especially in the early stages of recovery69.Additionally, irrelevant feedback can lead to decreased engagement and increased disengagement, particularly when patients perceive the feedback as overwhelming or unrelated to their personal goals70.

On the contrary, research by Choudhry and Gaalema72,73 highlights that highly relevant and tailored feedback can significantly improve patients’ understanding of rehabilitation and their motivation to engage. Personalized feedback that aligns with a patient’s individual needs and rehabilitation progress has been shown to enhance engagement and compliance by providing patients with a clear sense of purpose and understanding of their recovery journey. Thus, while feedback frequency (D1) must be balanced to avoid cognitive overload, the feedback relevance scores (D3),should always be relevant, timely, and specifically aligned with the patient’s health status and goals to ensure its effectiveness.

The unique role of psychological factors in rehabilitation compliance is also reflected in this study, especially the dual effects of depression and positive emotions on compliance. Depression can reduce patients’ initiative and execution. Research by Verplanken et al. also points out that attitude changes can lead to behavioral changes74. This is because depressed patients usually show low self-esteem and feelings of helplessness during the recovery process, which affects their engagement in rehabilitation tasks. In the present study, patients with higher depression scores show a significant inhibitory effect on the completion of specific rehabilitation activities, which is consistent with the findings of DiMatteo et al. on the negative impact of depression on long-term compliance75. In addition, Fredrickson’s positive emotion expansion theory states that positive emotions can help patients cope with rehabilitation challenges more effectively and improve self-efficacy76. The positive impact of positive emotions on rehabilitation program completion rates in this study further validates this theory, indicating the importance of emotional motivation on rehabilitation behaviors.To further enhance rehabilitation outcomes, practical approaches for emotional management should be integrated into rehabilitation programs. Strategies such as mindfulness-based interventions, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and regular emotional check-ins with healthcare providers can help patients manage their emotions effectively. These approaches can be tailored to individual needs and incorporated into the rehabilitation plan to support patients’ mental well-being throughout the recovery process.

Notably, the stability of the physiological variable heart rate plays an indirect supporting role in rehabilitation compliance. Heart rate stability can be used as a physiological marker of patient participation in rehabilitation. Its changes not only reflect the improvement of physical condition, but also form a positive feedback loop with rehabilitation initiative. This finding suggests that combining physiological monitoring and psychological support in rehabilitation design can not only enhance compliance, but also provide more intuitive rehabilitation feedback for clinical practice77.

In our study, physiological factors such as heart rate, blood pressure, and BMI showed limited or no significant effects on long-term rehabilitation adherence. However, it is important to acknowledge that these factors, although statistically non-significant in this model, may still play an essential role in the rehabilitation process. While direct correlations between physiological monitoring and rehabilitation adherence were not observed, physiological factors are crucial components of overall health and could influence patient outcomes indirectly78. Moreover, there may be an interaction effect with other factors, such as psychological factors and personalized feedback, which could make the role of physiological monitoring more prominent in future studies. Therefore, while physiological factors did not emerge as significant predictors in this model, their clinical relevance should not be dismissed. Further research could explore their combined effects with psychological and feedback variables to better understand how these factors collectively influence long-term adherence to rehabilitation programs.

In addition, although the interaction effect model of this study fails to show a significant synergistic effect between physiological and psychological factors, several factors may contribute to the lack of significance. First, the sample size may have been insufficient to detect subtle interaction effects, particularly in complex multidimensional constructs like physiological and psychological health. Moreover, the linear mixed-effects model used in this study may not be the most suitable for capturing the intricate and potentially non-linear relationships between these factors. Future research could explore alternative approaches, such as structural equation modeling (SEM), which allows for the modeling of latent variables and interactions in a more comprehensive way. Additionally, more refined techniques, such as multilevel modeling or non-linear modeling, may help better capture these interactions. Lastly, examining these effects within different patient subgroups could provide more insight into how these interactions might vary at different stages of recovery.

In summary, this study supports the key role of personalized feedback, psychological support, and time follow-up in rehabilitation compliance, and also proposes a strategy to integrate physiological and psychological monitoring to further optimize rehabilitation plans.While this study underscores the value of personalized feedback, psychological support, and time follow-up, implementing multimodal feedback systems in real-world settings presents challenges. Key difficulties include integrating various data streams (e.g., physiological, psychological) into a cohesive system and ensuring timely, relevant feedback tailored to individual patient needs. To address these, future research could explore AI-driven systems that deliver real-time, personalized feedback, along with training healthcare providers to effectively interpret and act on this data.

Future research should focus on more concrete and innovative directions to address the limitations identified in this study. Specifically, advanced analytical methods such as machine learning could be employed to better capture the complex interaction effects between physiological and psychological factors. Machine learning algorithms, including but not limited to Random Forests, Support Vector Machines, and Neural Networks, have the potential to identify subtle patterns and interactions that traditional statistical models may miss. Additionally, conducting randomized controlled trials (RCTs) could provide a rigorous validation of the proposed personalized feedback and multimodal monitoring approach. RCTs would allow for a more robust assessment of the intervention’s effectiveness in improving long-term rehabilitation adherence among elderly stroke patients. These studies should also consider the inclusion of diverse populations to enhance the generalizability of the findings.Moreover, considering the cultural and regional differences in rehabilitation practices, future research should explore how these factors may influence patient adherence and response to multimodal feedback systems. For instance, cultural attitudes towards rehabilitation, health literacy, and the availability of healthcare resources could significantly impact the effectiveness of personalized interventions. Such an exploration could help tailor future interventions to specific demographic and cultural groups, improving the generalizability of the findings.”

Conclusions

This study explores the role of time, personalized feedback, physiological and psychological factors in the long-term rehabilitation compliance of elderly stroke patients, and reveals the critical impact of these factors in improving patients’ rehabilitation participation and compliance. The study finds that patients’ rehabilitation plan completion rates, self-reported compliance scores, and completion of specific rehabilitation activities all improved significantly over time, especially with the continued effects of intensive follow-up and personalized feedback showing strong increasing trend of compliance. It reminds us that we can consider increasing the frequency of intervention in the early stage of rehabilitation to promote the establishment of behavioral habits, thereby improving the overall rehabilitation effect. Secondly, the application of personalized feedback mechanisms should focus on the effectiveness and relevance of feedback content rather than solely relying on feedback frequency. High-quality and closely related to the patient’s actual status feedback can significantly promote compliance, while feedback that is too frequent or irrelevant may have a negative impact on compliance, which has implications for optimizing information delivery strategies in rehabilitation plans. Finally, the roles of psychological factors and physiological factors in rehabilitation compliance show differences. Among psychological factors, positive emotions have a slight promoting effect on compliance, while depressive emotions have a significant negative impact on the interruption rate of rehabilitation activities, emphasizing the indispensability of psychological support in the rehabilitation process. Physiological factors have a relatively limited impact on improving overall compliance, but they may indirectly promote recovery effects under certain circumstances. Differentiated application and personalized adjustment of intervention strategies are needed. Psychological intervention, such as emotion management and motivation support, can directly improve patients’ willingness to recover and emotional stability, and reduce recovery interruptions caused by depression or low mood; while physiological monitoring and management can provide objective feedback on recovery progress and help patients real-time know their status.

Limitations

There are also limitations to this study that warrant further exploration.While the study acknowledges several limitations, it is important to highlight their potential impact on the findings. Firstly, the research was conducted in two hospitals within a specific region, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other regions or countries with differing healthcare systems and patient populations. Future studies could consider expanding to diverse geographic locations to increase the external validity of the findings. Secondly, our study excluded certain patient groups, such as those with severe comorbidities or cognitive impairments, which may impact the applicability of the results to broader patient populations. Including a more diverse sample of patients in future studies could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the multimodal feedback system’s impact.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

No comments:

Post a Comment