Now your competent? doctor and hospital can get human testing going.

Do you prefer your doctor, hospital and board of director's incompetence NOT KNOWING? OR NOT DOING?

Lymphoid gene expression supports neuroprotective microglia function

Nature (2025)

Abstract

Microglia, the innate immune cells of the brain, play a defining role in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)1. The microglial response to amyloid plaques in AD can range from neuroprotective to neurotoxic2. Here we show that the protective function of microglia is governed by the transcription factor PU.1, which becomes downregulated following microglial contact with plaques. Lowering PU.1 expression in microglia reduces the severity of amyloid disease pathology in mice and is linked to the expression of immunoregulatory lymphoid receptor proteins, particularly CD28, a surface receptor that is critical for T cell activation3,4. Microglia-specific deficiency in CD28, which is expressed by a small subset of plaque-associated PU.1low microglia, promotes a broad inflammatory microglial state that is associated with increased amyloid plaque load. Our findings indicate that PU.1low CD28-expressing microglia may operate as suppressive microglia that mitigate the progression of AD by reducing the severity of neuroinflammation. This role of CD28 and potentially other lymphoid co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory receptor proteins in governing microglial responses in AD points to possible immunotherapy approaches for tr eating the disease by promoting protective microglial functions.

Main

Alzheimer’s disease is associated with diverse phenotypic changes in microglia5,6, resulting in distinct microglial states, including protective (aimed at amyloid clearance and neuroprotection7,8,9) and harmful (associated with microglia-driven neuroinflammation and toxicity)10,11. These opposing states are accompanied by broad changes in gene expression12,13,14,15,16,17, suggesting that defined transcriptional programs in microglia may govern their neuroprotective or neurotoxic functions. Here we present evidence that the neuroprotective state of microglia is governed by reduced expression of PU.1, a non-canonical pioneer transcription factor that functions as a master regulator of myeloid and lymphoid lineage differentiation18,19,20. PU.1 regulates lineage-specific gene expression in a dose-dependent manner21,22,23. More recently, PU.1 abundance in microglia has been linked to AD risk. Human genetic data show that a common variant, located within the 3′ untranslated region of the PU.1-encoding gene SPI1 and associated with reduced PU.1 expression in myeloid cells, correlates with delayed disease onset and reduced severity24.

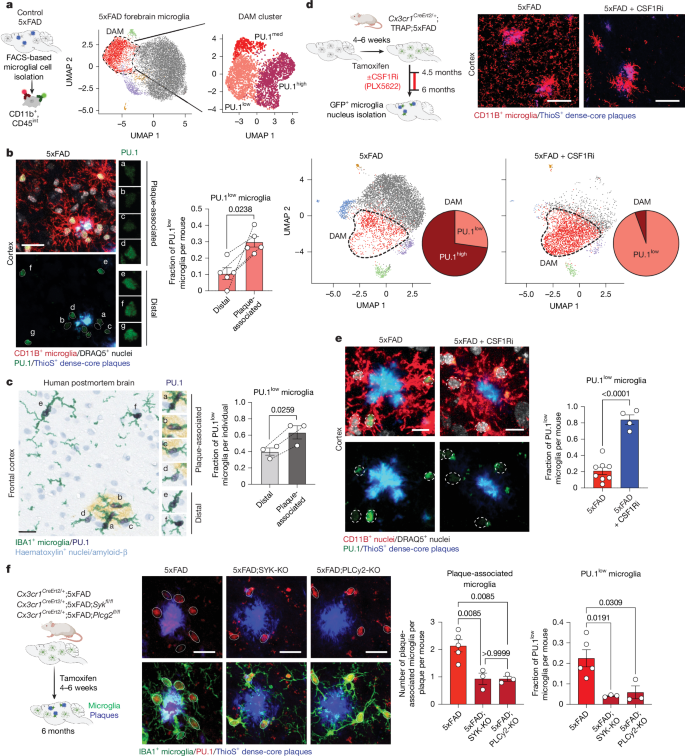

We found that PU.1 expression in microglia is regulated not only genetically but also epigenetically by the microenvironment. Using the amyloid-based 5xFAD mouse model of the disease25, we identified a distinct subpopulation of microglia, among the previously described disease-associated microglia (DAM)12 or neurodegenerative microglia13, that displays lower PU.1/Spi1 expression compared with the rest of the population (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1a–h and Supplementary Table 1). These PU.1low microglia preferentially co-localized with amyloid plaques, in both 5xFAD mice (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1i) and individuals with AD (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 2), and increase in numbers with disease progression (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Unlike non-plaque-associated (distal microglia; Extended Data Fig. 1b) or PU.1high plaque-associated microglia, this subpopulation appears independent of the activity of the essential microglial survival receptor CSF1R26,27 (Fig. 1d,e and Extended Data Fig. 1b–d). The CSF1R-independent survival of PU.1low microglia at plaques may reflect either their non-microglial origin or the engagement of alternative compensatory survival pathways. Lineage-tracing experiments using a microglia-specific genetic approach (translating ribosome affinity purification (TRAP) mice28; Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3) confirmed that the plaque-associated CSF1R-independent PU.1low cells, despite showing low Csf1r gene expression (Supplementary Figs. 1h and 2f), are bona fide microglia.

a, Uniform manifold approximation and projections (UMAPs) of ex vivo isolated forebrain microglia from 8-month-old wild-type and 5xFAD mice (two males per group) show distinct PU.1 expression states (PU.1low, PU.1med and PU.1high) among DAM12 (red). b,c, PU.1 protein is reduced in a subset of plaque-associated microglia in the cortex of 6-month-old 5xFAD mice (n = 5; one female and four males) (b) and in the frontal cortex of individuals with AD (79–91 years; n = 3; one female and two males) (c). Bar graphs show the proportion of PU.1low cells in plaque-associated microglia versus distal microglia, analysed using a paired two-tailed t-test. d,e, Plaque-associated PU.1low microglia are resistant to CSF1R inhibition (CSF1Ri). d, UMAP visualizations of lineage-traced cortical microglia (TRAP28) from 6-month-old control (one female) or CSF1Ri-fed 5xFAD mice (two males), analysed using single-nucleus sequencing (DAM outlined with dotted line). The pie chart shows PU.1low fraction within DAM. e, Reduced PU.1 protein expression in CSF1Ri-resistant cortical microglia in the cortices of 6-month-old CSF1Ri (n = 4; one female and three males) versus control diet-fed (n = 8 mice; six females and two males) 5xFAD mice. Bar graph shows the proportion of PU.1low microglia, analysed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test. f, Microglial SYK/PLCγ2 signalling promotes the plaque-associated PU.1low state. Representative images and quantification of PU.1 expression in cortical microglia from 6-month-old 5xFAD;Cx3cr1CreErt2/+ (n = 5; three females and two males), 5xFAD–SYK-KO (5xFAD;Cx3cr1CreErt2/+;Sykfl/fl; n = 3; one female and two males) and 5xFAD–PLCγ2-KO mice (5xFAD;Cx3cr1CreErt2/+;Plcg2fl/fl; n = 3; two females and one male). Bar graphs show plaque-normalized microglial numbers and PU.1low microglia fractions, as determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. Microglial nuclei identified using Imaris (b,f) and CellProfiler (e) in dotted circles. Bar graphs show the mean ± s.e.m. with individual points. Scale bars, 20 μm (b,c,f), 40 μm (d), 10 μm (e). Illustrations in a, d and f were created using BioRender (https://biorender.com).

The PU.1low microglial population at amyloid plaques may be established either through a pre-existing PU.1low microglial subpopulation that is recruited specifically to plaques or by the downregulation of PU.1 expression in microglia in response to plaque-associated cues. Our data support the latter mechanism. Microglial accumulation at plaques and plaque-driven morphological and transcriptional responses depend on microglial surface receptor-mediated signalling8,12,13,29, which involves activation of the tyrosine kinase (SYK)9,30 and one of its key downstream targets (PLCγ2)31,32. Microglia-specific inactivation of either SYK (5xFAD;Cx3cr1CreERT2/+;Sykfl/fl; referred to as 5xFAD;SYK-KO) or PLCγ2 (5xFAD;Cx3cr1CreERT2/+;Plcg2fl/fl; referred to as 5xFAD;PLCγ2-KO), which impairs microglial engagement with the plaques9,30,32 (Fig. 1f), also significantly reduces the number of PU.1low microglia (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 1e) and averts their CSF1R-independent survival at the plaques (Extended Data Fig. 1f).

Activation of SYK–PLCγ2-dependent signalling pathways in plaque-associated microglia occurs following the engagement of surface receptor proteins, including TREM2, CLEC7A and FcγR33. To confirm that PU.1 downregulation is driven by surface receptor-mediated signalling, we exposed ex vivo isolated microglia to phosphatidylserine/phosphatidylcholine (PS/PC)-containing liposomes31 or β-1,6-glucan pustulan34, which engage TREM2 and CLEC7A, respectively. Both ligands induced PU.1 downregulation (Extended Data Fig. 2a–d), which was attenuated by pharmacologic inhibition of downstream phospholipase C (PLC) activity35 (Extended Data Fig. 2e,f). Conversely, activation of PLC36 was sufficient to downregulate PU.1 even in the absence of external ligands (Extended Data Fig. 2e), confirming that activation of the SYK–PLCγ2 signalling pathways triggered by plaque-associated cues can regulate PU.1 expression in microglia.

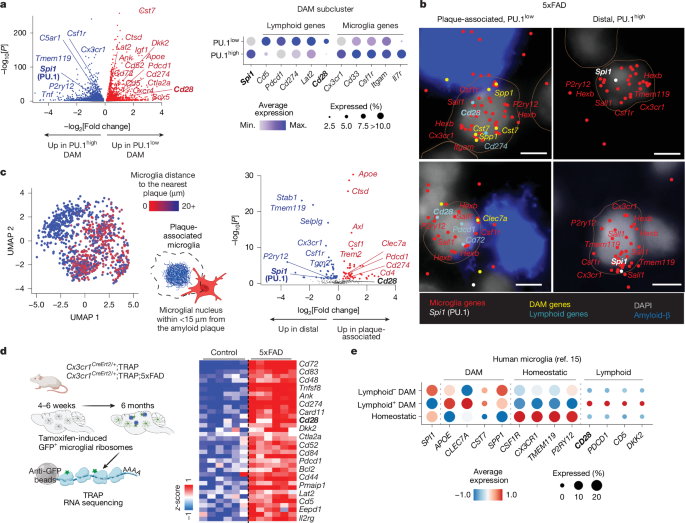

The PU.1low plaque-associated microglia displayed gene expression patterns that, in addition to promoting lipid metabolism and lysosomal function37,38,39,40 (Extended Data Fig. 3a), showed a resemblance to lymphoid lineage cells (Fig. 2 and Extended Data Fig. 3). Microglial single-cell (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Table 1), lineage-traced single-nucleus (Extended Data Fig. 3c–e and Supplementary Table 3) or spatial transcriptomics analyses (Fig. 2b,c, Extended Data Fig. 3f,g, Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 4) revealed that PU.1low plaque-associated microglia express genes encoding immunoregulatory lymphoid receptors and signalling proteins, such as CD28, PD-1 (Pdcd1), PD-L1 (Cd274), CD5, CTLA-2A, CD52, LAT2 and CD72 (Extended Data Fig. 3d). The transcripts encoding these proteins are associated with ribosomes in 5xFAD microglia (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 5), suggesting their translation and protein expression. Microglial lymphoid gene expression in PU.1low disease-associated microglia (DAM) is not restricted to mice but is also observed in individuals with AD15 (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 5).

a, The volcano plot shows genes upregulated in PU.1low (red) versus PU.1high (blue) DAM in 8-month-old wild-type and 5xFAD mice (two males per group), as determined by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The dot plot highlights selected myeloid/microglia-associated and lymphoid-lineage-associated genes in PU.1low and PU.1high DAM. b,c, PU.1low lymphoid gene-expressing cortical microglia localize near amyloid plaques. Independently repeated twice. b, Representative MERFISH images of plaque-associated and distal microglia from an 8-month-old male 5xFAD brain. c, UMAP of spatial microglia distribution to the nearest plaque using MERFISH. The volcano plot shows differentially expressed genes in plaque-associated microglia (red; less than 15 μm to plaques) versus distal microglia (blue; greater than 15 μm to plaques), as determined by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. d, Lymphoid protein-encoding RNAs associate with ribosomes in lineage-traced microglia. The heat map (z-score) shows selected lymphoid lineage genes identified using microglia-specific TRAP sequencing28 from the cortices of 6-month-old 5xFAD mice (Cx3cr1CreErt2/+;5xFAD;Eef1a1LSL.eGFPL10a/+) versus control (Cx3cr1CreErt2/+;Eef1a1LSL.eGFPL10a/+ mice; n = 6 per group; three females and three males), as determined using DESeq2. Each column represents an individual mouse. e, PU.1low lymphoid gene-expressing microglia are present in individuals with AD. The dot plots show scaled average expression of selected genes in human microglia15 organized into homeostatic, lymphoid+ DAM and lymphoid– DAM clusters. Scale bar, 5 μm. Illustrations in c and d were created using BioRender (https://biorender.com). Max., maximum; Min., minimum.

No comments:

Post a Comment