I bet our fucking failures of stroke associations have no clue as to when we might get solutions to all these problems in stroke. Mainly because without a strategy to follow, researchers are blindly flailing in the dark hoping to hit a stroke bullseye without even knowing if they are pointed in the right direction. This is so simple to fix. The first objective is to create a strategy, then we can deploy money and research to find solutions.

Despite failed trials, experts believe we'll have an Alzheimer's drug by 2025

The results of recent trials that tested much-anticipated Alzheimer's disease drugs dashed the hopes of patients with the debilitating condition. The most recent disappointment came from the large trial for solanezumab, by Eli Lilly, announced last month.

But

experts across the field say hope is not lost. They believe we will

have some form of drug against the disease by 2025, albeit most likely a

pilot version that will need to be upgraded.

This target, in less than a decade, is the goal set by world leaders at the G8 dementia summit in 2013. (Where is the stroke goal?)

Researchers believe there are enough competitors in the race to get at least a few to the finish line on time.

"There

are still a number of late-stage trials in progress," said Heather

Snyder, senior director of medical and scientific operations at the

Alzheimer's Association. "2025 is a realistic target in terms of where

we are with the science. ... We're not off-track at this point in time."

Twenty-four

drug candidates are currently in phase 3 trials on humans -- trials

that involve larger numbers of people and a comparator to see a drug's

true effect -- and many more potential drugs are in earlier stages of

development. Speaking from the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer's Disease conference in San Diego this week, Snyder is hopeful that a few drug options -- not just one -- may surface to one day treat Alzheimer's at various stages of the disease.

The

question now is, which trials will they be? Unlike with many other

diseases, scientists don't fully understand the underlying causes of

Alzheimer's, meaning drugs now in development are targeting different

aspects of what is theorized to cause symptoms.

"This

is a complex disease," Snyder said. "If you think of HIV or cancer ...

we don't treat those diseases with one drug." The end result may have to

be a combination therapy.

It's estimated that 46.8 million people were living with dementia worldwide in 2015, of which Alzheimer's disease is considered to be the leading cause. More than 5 million people are living with the condition in the United States.

Ahead in the race

On

Thursday, Biogen presented at the San Diego conference and announced

further promising results from its experimental drug aducanumab, an

antibody-based therapy, which saw significant reductions in amyloid

plaques in the brain of patients when compared against a placebo. This

is one of three drug candidates in trials led by the company.

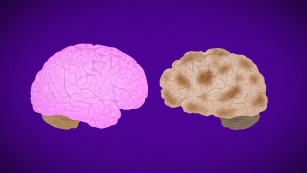

More

than half of the drugs in current late-stage trials target these

β-amyloid proteins, which stick together to form plaques between nerve

cells in the brain's of Alzheimer's patients. The plaques destroy

surrounding cells and impair cognition.

Drugs

reducing the existence of these plaques are one of the big goals to

provide an effective therapy, and Biogen's trial on patients with mild

or presymptomatic Alzheimer's disease saw a statistically significant

reduction in these plaques, as well as a slowing of mental decline, at

the 12-month mark. This followed strong results announced earlier this year.

"It's

our most developed program in Alzheimer's disease," said Samantha Budd

Haeberlein, vice president of clinical development at Biogen. "The

degree of effect we had regarding the reduction of amyloid plaques ...

was very exciting."

The drugs will

soon enter into a new trial including almost 3,000 people across 20

countries to test the outcome on multiple populations. "It's a global

clinical trial," said Budd Haeberlein.

Budd Haeberlein believes

that targeting plaques is key to getting the first therapies going, as

the plaques appear in the brain up to 20 years before symptoms begin.

"It's important in reducing the impact of the disease," she said.

Starting from the BACE

Another

approach many in the field are picking as the favorite in terms of

potency to fight plaques in the brain is the use of drugs known as BACE

inhibitors, which block the production of an enzyme -- β-secretase --

needed for the production of β-amyloid proteins.

By

blocking the production of the protein itself rather than killing it

once it's formed, it's hoped the impact could be more potent within the

brain.

"I think BACE is a great target," said John Hardy, professor of neuroscience at University College London in

the UK, who first proposed that these proteins, and plaques, were to

blame for the development of Alzheimer's disease. Twenty-five years

after he first thought up the theory, he believes a drug preventing

their formation could be the winning formula.

But Hardy worries that drugs are being targeted at patients too late. "To attack amyloid is to attack earlier," he said. "It might be being given too late."

One

of many companies testing this method is Eli Lilly. It hasn't let the

failure of its solanezumab drug hold it back. "We've seen that BACE

inhibitors can decrease amyloid protein production," said Dan

Skovronsky, senior vice president of clinical and product development at

Eli Lilly.

Its candidate in this

group, known only as AZD3293 for now, is in phase 3 trials and was

bumped ahead in the drug race this year. It was given fast-track designation from the US Food and Drug Administration, which should help expedite its route to the market.

Tearing apart the tangles

Although

they may be talked about more often, plaques are not the only theory

among scientists to explain how Alzheimer's disease occurs.

Another suspect thought to play a key role is a protein known as tau, which forms tangles inside cells in the brain.

The

twisted tangles are thought to block the transport of nutrients in

cells, causing them to die. But these are formed much later in the

disease than the plaques, resulting in faster cognitive decline.

"Tangles

actually spread across the brain," said Skovronsky, whose colleagues at

Eli Lilly have developed imaging technologies to identify their

presence inside the brain. "Our aim is to block their spread ... but

it's been more difficult to attack the tangles."

Two of eight drugs Eli Lilly has in development are targeting these tangles inside the brain.

"We

didn't have a way of seeing them until now," he said. "(They) develop

later, and as people progress through the disease, they get more

tangles."

The Alzheimer's

Association's Snyder believes the tangles are an important target for

effective drug therapies, as they act as a better predictor of dementia

symptoms.

A drug recently trialled

to bust these tangles was LMTM, by TauRx pharmaceuticals. It failed to

reveal significant benefits to patients, but a small group did see

improvements in cognitive testing, meaning all was not lost.

Presenting

at the conference on Thursday, the company announced it was conducting

trials specific to populations that are most likely to benefit -- in

this case, patients with mild or probable Alzheimer's disease. "We're

hoping for optimistic results coming out of these trials," said Snyder.

But

Hardy is not so optimistic, believing that although tau proteins are a

good target, this is not the drug to do the job. "Tau is the right

target ... (but) that's a terrible drug," he said, questioning the

approach of bursting the tangles apart.

With

so much in the pipeline, two points are clear: There is unlikely to be

one drug that will beat Alzheimer's in all patients affected, and the

aging population around the world means a greater number will need them

once they become available.

"We

will still see millions with the disease ahead. ... It might be then,

that in the future, we need to target multiple therapies," Skovronsky

said. "We're not giving up on Alzheimer's patients, that's for sure."

No comments:

Post a Comment