We don't SPECIFICALLY know why a neuron gives up its' current job and takes on a neighbors. Thus nothing on neuroplasticity is scientifically repeatable on demand. So, DEMAND your doctor give you EXACT PROTOCOLS to use. Don't allow your doctor to give you generalities or guidelines.

The latest here: which tells us nothing helpful

Remodeling and repair of the damaged brain: the potential and challenges of organoids for ischaemic stroke

Journal of Translational Medicine 23, Article number: 767 (2025)

Abstract

Ischemic stroke induces irreversible cerebral tissue damage, a condition exacerbated by the brain’s limited endogenous neuroplasticity and inability to regenerate neurons. While neural circuit reorganization holds therapeutic potential, its efficacy is hindered by pathological barriers such as glial scarring, chronic inflammation, and neurotrophic factor deficiency. Although pharmacological and interventional methods for stroke have been well developed, their functional recovery outcomes remain suboptimal. Emerging neural regeneration paradigms, particularly stem cell-based strategies (encompassing neural stem cell transplantation, neural progenitors grafts, and 3D brain organoid implantation), offer novel solutions to these challenges. However, critical limitations persist in conventional stem cell approaches: (1) compromised synaptic integration efficacy hinders functional neural circuit reconstruction; (2) the absence of functional vascular niches coupled with deficient astrocyte-mediated support and extracellular matrix signaling; (3) restricted regenerative capacity despite theoretical multipotent differentiation potential. Recent breakthroughs in cerebral organoid technology have revolutionized neurological disease modeling and neural repair research. Building upon this paradigm shift, our study mechanistically interrogates neuroplastic remodeling processes following ischemic stroke, while critically evaluating the therapeutic efficacy and inherent limitations of stem cell-based interventions. This affirms the critical role of 3D human cerebral organoid transplantation in the reconstruction of neural circuits. Additionally, we further summarize the utility of organoid-based disease models and address associated ethical and societal concerns. Future efforts should prioritize the clinical translation of organoid transplantation for ischemic stroke, aiming to mitigate neurological deficits and restore functional recovery.

Introduction

Stroke, a cerebrovascular disease, is the second leading cause of death globally and the third leading cause when disability and mortality are included as compounding factors [1]. Accounting for 62.4% of all strokes, ischemic stroke is the most frequent type and is the leading cause of neurological dysfunction encountered in clinical practice. Stroke imposes a significant economic and social burden and severely impacts the healthy lives of individuals worldwide [2]. Despite the high incidence of cerebrovascular diseases such as stroke, only a limited number of effective therapies are available in clinical practice. This, along with the fact that most patients do not seek timely medical attention for treatment, delays the optimal time for treatment and leads to extensive necrosis in the infarcted area, which can cause irreversible damage to the neurons in the brain. After patients progress through the acute phase of a stroke, they are left with serious sequelae, such as motor dysfunction. Post-stroke motor impairments typically affect the face, arms, and legs on one side of the body, impacting approximately 80% of patients [3]. Recovery is often prolonged and can severely impact the patient’s daily work and life. Longitudinal follow-up data reveal that approximately 50% of patients continue to experience motor deficits four years after their stroke occurred [4]. Clinics currently use pharmacological thrombolysis as the primary treatment to restore cerebral perfusion [5]. Although many drugs show neuroprotective effects in both preclinical studies and animal models, they have not demonstrated satisfactory results in clinical practice. Differences in physiology between species pose a challenge to the clinical translation of disease research [6].

Neurorestorative therapies for stroke typically extended therapeutic timeframes from days to weeks after stroke onset and aim to improve neurovascular remodelling and synaptogenesis while decreasing inflammatory and immune responses [7]. Stem cell therapy in regenerative medicine offers novel therapeutic paradigms [9]. Cell therapy enhances the recovery of neurological function of the body through sophisticated neuroimmune modulation and trophic factor secretion [8], thereby avoiding the suboptimal functional outcomes associated with conventional stroke treatments and showing substantial developmental potential [10]. Neural stem cells (NSCs) exhibit multimodal therapeutic actions that can stimulate functional neural replacement or induce multimodal therapeutic actions across multiple central nervous system (CNS) regions [11]. Effectively combining the anti-neuroinflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and pro-angiogenic capacities properties of NSCs with other interventions (e.g., recombinant tissue plasminogen activator) may mitigate apoptosis and necrosis caused by the generation of excess reactive oxygen species (ROS). This excess ROS is generated when the therapeutic time window for restoring blood flow during rt-PA therapy is missed, resulting in reperfusion injury (RI). However, transplantation of cells after 2D monolayer culture is less effective in repairing the tissue structure of the infarcted core compared with culturing cortical organoid systems in a 3D structure. More importantly, cerebral organoids (COs) not only demonstrate efficacy in repairing the ischemic core but also exhibit lesion-targeted neurogenesis into lesion-specific neurons. These neurons extend axons to cortical-basal ganglia-thalamic circuits, establishing functional synaptic connections with the host neural network to reconstruct complete neural circuits. They also demonstrates measurable efficacy in ameliorating post-stroke sensorimotor dysfunction [12]. Currently, several technologies are available to improve the reproducibility of cerebral organoid culture, such as 3D printing to help manipulate the size, shape, and organisation of organoids [13] and Notch signalling inhibition to prevent cell proliferation, induce terminal differentiation, and promote cerebral organoid maturation [14]. Therefore, based on the feasibility and therapeutic potential of generating and optimizing human cerebral organoids, the clinical translation of organoids for enhancing the neuroregenerative capacity and functional remodelling of the brain is a translational research priority.

Mechanisms of neuroplasticity after stroke onset

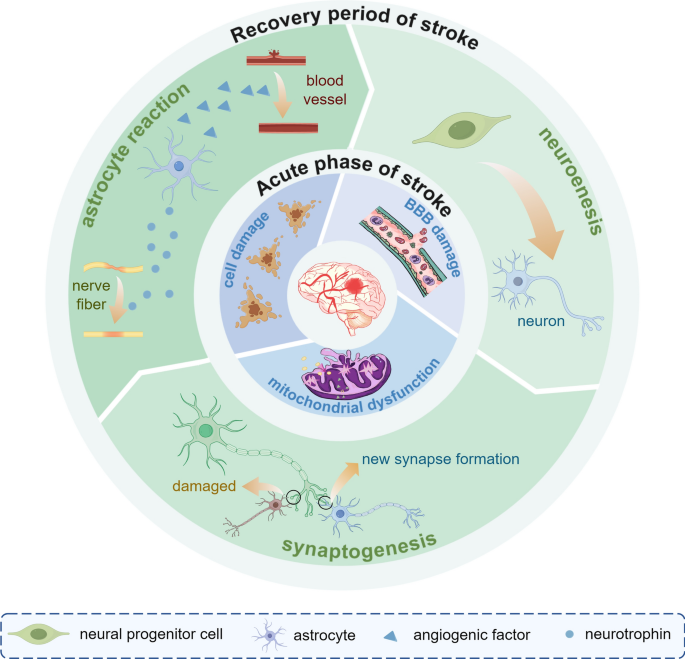

Brain recovery after stroke injury is dynamic and phase-dependent process. In early neurodevelopment (0–3 years), as the brain begins to develops, a large number of synapses are formed to sensory processing and multimodal integration and explore the comprehensive neural network [15]. During the initial development of the brain, the number of dendritic spines and synapses increases substantially, peaking at five years of age, after which the number decreases [15]. As brain volume expansion slows in the later stages, the energy needs of neuronal and synaptic activities cause the brain to adjust the density of these structures through selective synaptic elimination, transitioning from high plasticity to functional [16]. Stroke survivors show a sustained recovery of motor abilities over many years following brain injury. This recovery process is somewhat similar to how infants learn motor function [17]. The Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation Roundtable has established a time frame for recovery of stroke patients, which is differentiated into the following four phases: the hyper-acute phase (0–24 h), the early subacute phase (7 days–3 months), the late subacute phase (3–6 months), and the chronic phase (>6 months) [18]. After a stroke occurs, the brain undergoes a series of ischemic cascade changes during the acute phase. Due to the disruption of blood flow to the brain and ATP depletion, neurons are unable to maintain normal transmembrane ion concentrations, resulting in a cascade of apoptosis and necrosis [19]. Hypoxia and depletion of metabolic substrates, as well as a substantial reduction in neuronal energy failure, subsequently causes structural damage to the brain [20].Therefore, ionic imbalance and cell death are the primary mechanisms at the onset of a stroke. In the subacute phase of stroke recovery, neuroinflammation diminishes while functional brain networks exhibit activity-dependent neuroplastic changes [21]. Microglia and monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) release factors that facilitate adaptation to resolving inflammation by removing neutrophils, cellular debris, and apoptotic cells [22]. These spontaneous neuroplastic changes include the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor [23], structural remodelling at synaptic, axonal, and dendritic levels [24], and the activation, migration, and differentiation of endogenous neural stem cells [25]. During the chronic phase, experience-dependent reorganization of the neural network stabilizes, and long-term adaptation begins. At this point, “auto-reactive” lymphocytes sensitive to brain antigens return to the brain, triggering chronic inflammation and cytotoxicity, which likely contribute to the chronic sequelae of stroke [26]. Figure 1 Rehabilitation during the early subacute phase, when heightened neuroplasticity is at its peak, substantially increases both the speed and extent of patient recovery [18]. Although spontaneous remodeling occurs after ischemic stroke, these changes alone are insufficient to produce significant functional recovery [27]. In the future, functional recovery through cortical neuronal replacement may be the key to curing human neurodegenerative diseases [28, 29]. Compared with the use of dissociated neural progenitor cells, cerebral organoid transplantation offers several advantages, including a diverse cellular composition, maintenance of a native microenvironment, greater surgical feasibility, and higher vascularization potential, making it a promising therapeutic approach for restoring brain function in both the subacute and chronic phases of the disease [30].

The main pathophysiological mechanisms of IS in the acute and convalescent phases. In the acute phase of IS, the ischaemia and reperfusion injury lead to mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular damage, and impairment of the blood–brain barrier. As IS interrupts the normal synaptic plasticity, during the recovery period, homeostatic plasticity is up-regulated and neurogenesis and synaptic remodelling occur. In addition, new synapse formation builds new circuits and aids brain recovery. In the cellular response mode, astrocytes secrete neurotrophic and angiogenic factors to repair damaged blood vessels and nerves. IS ischaemic stroke

No comments:

Post a Comment