I bet your incompetent? doctor will ignore this advice just like they ignored the dairy fat one!

dairy fat (40 posts to April 2016)

For Brain Health, Is Cheddar Better?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson from the Yale School of Medicine.

I was lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, spending a year between college and medical school working as a singing waiter in a restaurant called the Hollywood Savoy in the 2nd arrondissement. It’s still open, but it looks like the waiters don’t sing anymore. Tant pis.

In any case, living on a French waiter’s salary back then wasn’t easy. There were no tips. So I subsisted, as I imagined Hemingway did in his Moveable Feast days, on a diet composed almost entirely of wine, baguettes, and goat cheese. This might not have been the best for my GI health, but according to a new study at least, all that cheese intake might serve to protect my brain in the long term.

That’s right. This week, nutritional epidemiology rears its delicious head again as we discuss whether high-fat-cheese-eating prevents dementia.

The public gets understandably frustrated with new studies that suggest that a particular food or ingredient is healthy, or unhealthy, or should be avoided at all costs. And this paper will have the same effect. Think of all the “balanced diet” advice you’ve ever heard: Eat a mix of fruits and vegetables, grains and low-fat dairy — you know: yogurt, cottage cheese, and so on.

And yet here we have a study, “High- and Low-Fat Dairy Consumption and Long-Term Risk of Dementia,” appearing in the journal Neurology, that turns that dairy part on its head. It’s the high-fat cheese that is good for you after all. Throw out your part-skim mozzarella and pass the Stilton. For someone like me, this sounds too gouda to be true.

Let me walk you through how the study worked.

Researchers used the Malmö Diet and Cancer cohort, a long-running population cohort study out of Sweden. From 1991 to 1996, as new participants were brought into the study, a fairly detailed dietary profile was created. This included data from food diaries, a dietary interview, and, of course, my old nemesis: the food frequency questionnaire, which I take to task in my book about medical research. Still, let’s take it on faith that, broadly, researchers captured how much dairy, and how much high-fat dairy, people were eating.

After the initial collection of data, the participants were followed for around 25 years through the national electronic health record system of Sweden. Researchers used those records to identify new cases of dementia and to subset those cases into vascular causes of dementia and Alzheimer's disease. These diagnoses were based on administrative codes but validated in a subset with direct review, which revealed pretty high fidelity.

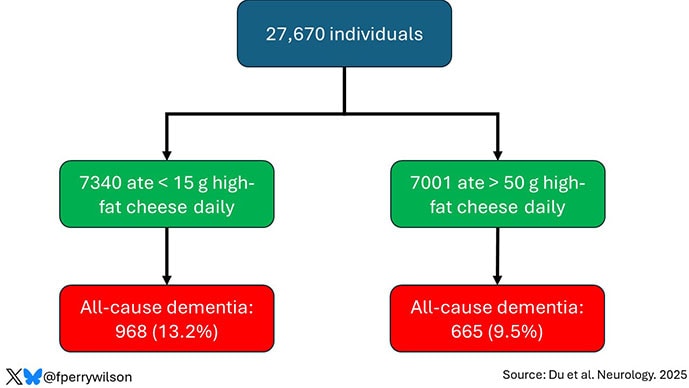

All told, 27,670 individuals were analyzed. Of those, 3208 (11.6%) developed dementia over those 25 years of follow-up.

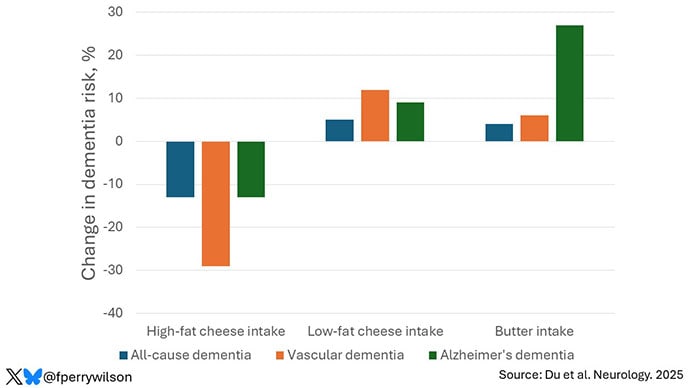

The people who ate more high-fat cheese were less likely to be in that 11.6% group. According to the study, they had about a 13% lower risk for all-cause dementia and a 29% lower risk for dementia than those who didn’t eat much high-fat cheese. There was no significant relationship between cheese intake and Alzheimer's disease.

OK. The first thing we need to remember when we are thinking about a nutrition study is that food is complicated. Cheese, even high-fat cheese, is not one thing, one chemical, the way a medication or vitamin or even amino acid is. It’s an incredibly complex mixture of fats, proteins, enzymes, bacterial cultures, molds, salt, vitamins, and minerals. Finding a signal of benefit from a foodstuff like cheese is problematic, because even if it is real, we may never discover what thing in the cheese is driving that benefit.

The study looked at other dairy intake as well and, frankly, that made me more confused about these cheese results. If it’s the protein content in the cheese that is beneficial, then we should see a protective signal from low-fat cheese intake, but we don’t. If it’s the fat that is protective, you’d think we’d see a protective signal from butter, which is about 80% milkfat, but we don’t. So, we’re left having to wave our hands about some complex interaction of various brain-protecting substances that exist only in high-fat cheeses. Possible? Maybe. Likely? I don’t think so.

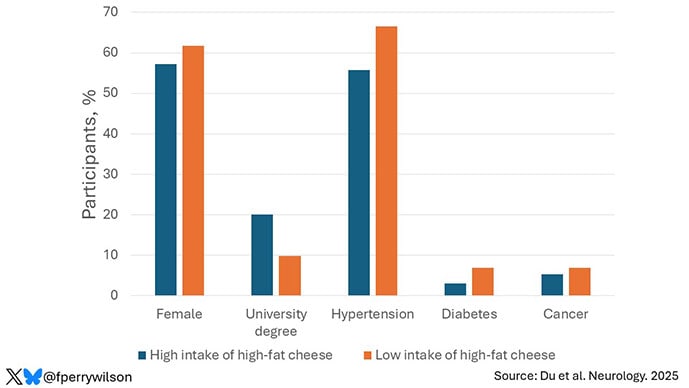

But beyond that, food is a cultural phenomenon. What you eat varies dramatically based on who you are and, dare I say it, what you can afford. It has not escaped my notice that high-fat cheeses — your mascarpones and aged cheddars — tend to be more expensive than their lower-fat counterparts. They therefore may be consumed by people of higher socioeconomic status.

There’s direct support for this hypothesis in the study, by the way. High-fat cheese eaters were younger, less likely to be female, had a lower BMI, and were twice as likely to have a university degree. They were also less likely to have hypertension, diabetes, or a cancer history.

The authors adjusted for these factors as best they could, of course, but adjustment is virtually never perfect and relies on how precisely you can measure the cultural factors that might associate with high-fat cheese intake. That’s not easy. So, I am always inherently skeptical of findings of health benefits of foods that are a little more costly than their alternatives. I always believed that red wine was firmly in this category, and although no one has studied it, I suspect that those who eat more foie gras also have better health outcomes.

One mechanism that I do find plausible for the protective effect of high-fat cheese is via food substitution. The idea is that when you eat certain high-fat foods, you may eat less of other foods that scratch that same itch; think red meat for the umami-ness of it all, or processed meats for the saltiness. The authors analyzed the data with this in mind and indeed showed that replacing the high-fat cheeses with some of these other foods increased dementia risk. This suggests that there may not be anything magic in cheese itself; instead, cheese helps us resist the temptations of the foods that are really bad for our brains. Could be.

Still, most people who see headlines about this study are likely to end up confused. What am I supposed to do: High-fat dairy or low-fat dairy? Gruyère or ricotta? We are all looking for that “one simple thing” we can do to change the trajectory of our health. But the truth is that there is no “one simple thing.” No one food will prevent dementia. No one exercise will give you six-pack abs. No one supplement will keep you young and full of energy as time goes on. To really change the trajectory of our health, we have to be willing to change our lifestyles in pretty substantial ways. That’s never going to be one simple thing, it won’t be easy, and it definitely won’t be delicious.

With that said, though cheeses may not protect your brain over time, many will absolutely delight your senses in the moment. And if this paper, or my commentary on it, gives you a bit more permission to enjoy that baguette and chèvre, well, I think you should do so. Bon appétit.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He posts at @fperrywilsonand his book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

No comments:

Post a Comment