Your doctors don't understand neuroplasticity either yet want you to use it for recovery. Hasn't your competent doctor been treating your PTSD with psychedlics for years now?

Since there is a 23% chance of stroke survivors getting PTSD what is your doctor's treatment plan?

Harnessing Psilocybin to Treat PTSD

Treating PTSD With Ecstasy? You Might Have Some Questions. May 2018

Ecstasy Was Just Labelled a 'Breakthrough Therapy' For PTSD by The FDA August 2017

But this negative action:

The latest here:

Psychedelics may rewire the brain to treat PTSD. Scientists are finally beginning to understand how.

Creating a safe space to process trauma

For Jennifer Mitchell, a neuroscientist and the associate chief of staff for research and development at San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center, it was imperative to find effective treatments for military veterans suffering from PTSD.

"I see how debilitating it is for individuals that have served and have experienced combat," Mitchell told Live Science. "And we absolutely owe them to come up with better treatments."

Nearly a decade ago, Mitchell and her colleagues began to investigate whether MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine), commonly known as ecstasy or molly, could treat PTSD when used in conjunction with psychotherapy. In 2023, the team published their findings on a diverse group of 104 participants with PTSD from the general population, 80% of whom had a history of contemplating suicide. By the end of the study, 71% of the participants who'd received MDMA no longer met the criteria for PTSD, and another 15% still had symptoms but had what the researchers termed a "clinically meaningful benefit."

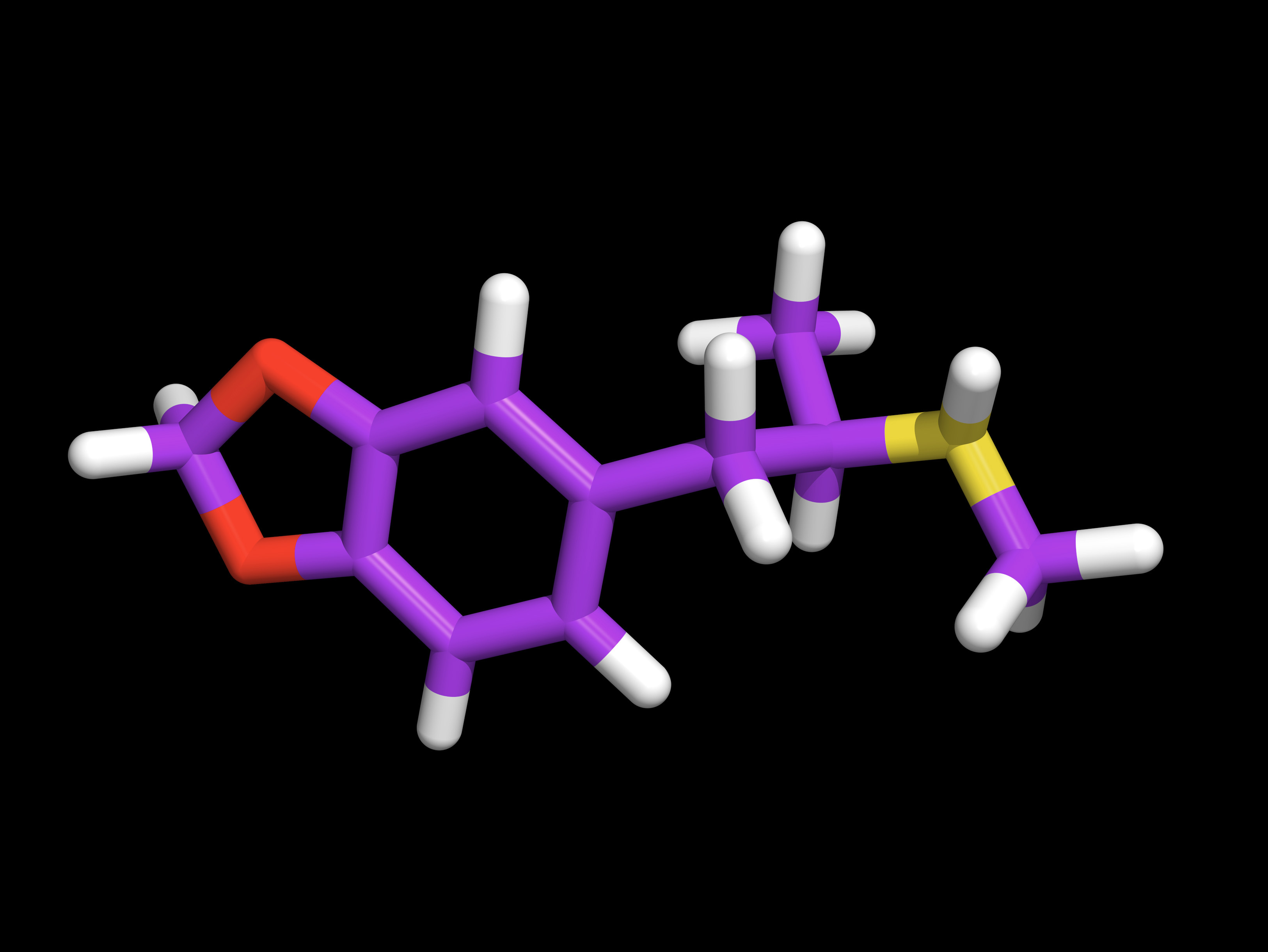

MDMA's effectiveness hinges partly on its ability to act as a neuroplastogen — a compound that harnesses the brain's ability to form new connections and strengthen and reorganize existing connections. In the past few years, scientists have begun to explore the potential for another neuroplastogen to treat PTSD: psilocybin.

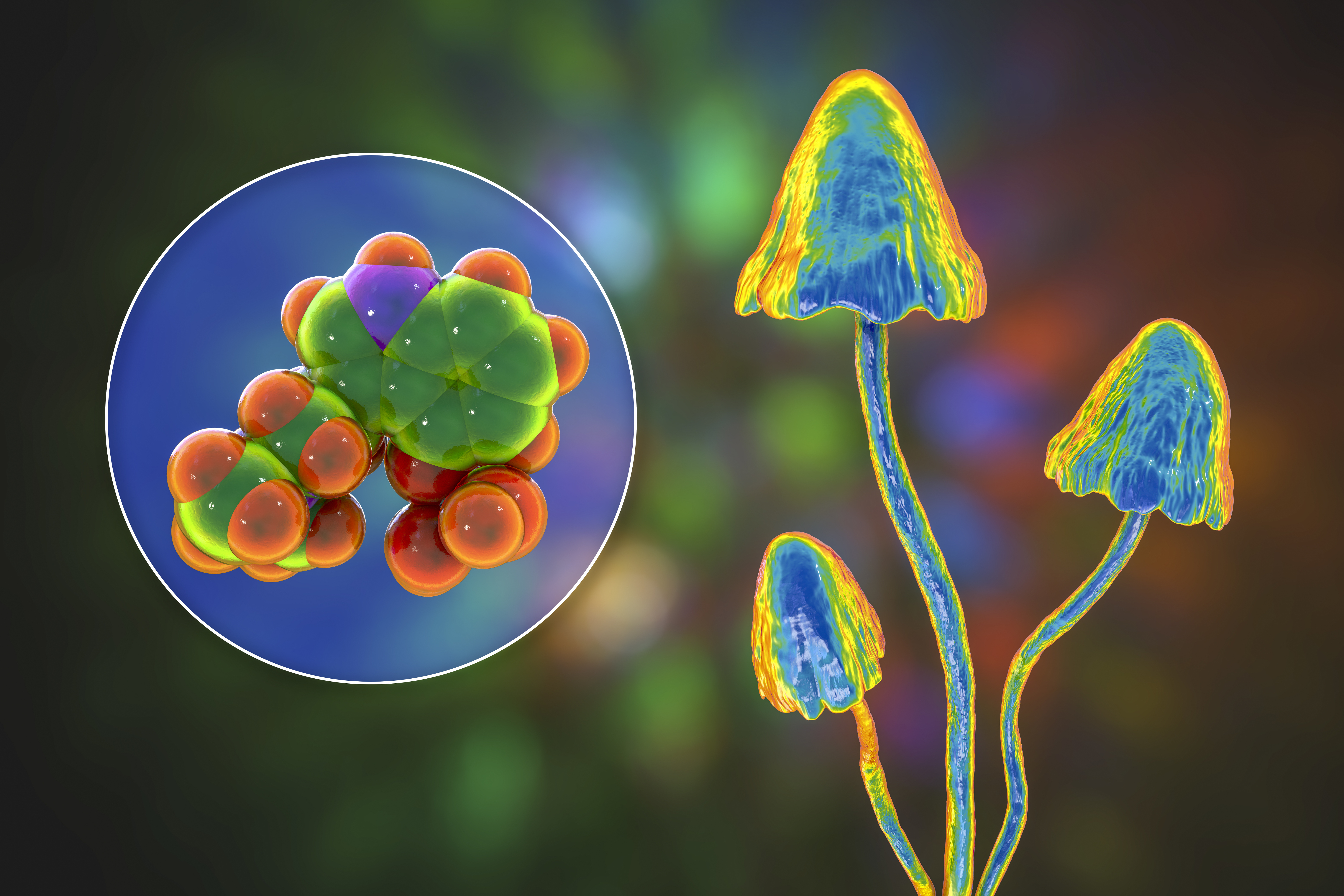

Clinical trials have found psilocybin, the main psychoactive ingredient in magic mushrooms, to be a promising therapy for treatment-resistant anxiety and depression, and studies conducted on animals have pointed to its potential for treating PTSD.

A study on mature adult mice demonstrated that MDMA temporarily reopens a critical period for where the brain is sensitive to learning that social behaviors are beneficial by inducing structural and functional changes in the brain’s reward circuits. Specifically the drug makes the nucleus accumbens reward circuitry more sensitive to the social hormone oxytocin. This enhanced sensitivity allows the adult brain to re-encode social cues as intrinsically rewarding and safe, facilitating the re-learning of trust and attachment for up to two weeks after a single dose, the researcher theorize.

Mitchell has witnessed similar responses in humans and hypothesizes that the drug creates a neurobiological state in which patients can form a strong, trusting bond with a therapist. "There's a therapeutic window where people feel renewed energy, they don't feel so stuck, and they can actually work on the psychological side of their issues," Mitchell said.

Simultaneously, functional neuroimaging data points to MDMA's impacts on the fear circuitry of the brain. The drug decreases activity in the amygdala while increasing activity in the prefrontal cortex. MDMA also restores normal levels of BDNF in the amygdala, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, theoretically leading to the formation of new synapses and structural changes that enable greater plasticity in these regions.

Researchers hypothesize that the dampening of the fear response, the enhancement of the prefrontal cortex's regulatory role, and the restoration of flexibility in key brain regions set the scene for patients to revisit and reprocess memories without being overwhelmed by fear. By entering therapy with this more regulated perspective, recovery can happen quickly.

"By the end of a treatment session, you can see that something has shifted. The subject will be holding themselves differently and look hopeful," Mitchell said. "I've been doing this type of research for 35 years, and it is the most remarkable thing that I've seen."

Once the patients have analyzed and processed their trauma, they are less likely to slip back into their PTSD symptoms after MDMA, Mitchell said. The researchers collected data on the patients in increments over the two years after their treatment ended, and the positive benefits appear to be durable, Mitchell said.

Breaking free

When a single dose of psilocybin was injected into chronically stressed mice that had developed learned helplessness and avoidance behaviors, for example, researchers could see immediate and enduring structural changes in the rodents' brains. The rapid increase in dendritic spines — the tiny protrusions that form synapses, the connections between brain cells —suggests that psilocybin may directly reverse the loss of neuronal connections observed in the frontal cortex of rodents subjected to chronic stress, the authors suggest. And the changes could prepare the brain for fear extinction and emotional processing —key elements of overcoming trauma.

Consequently, several trials are underway to investigate psilocybin as a treatment option for PTSD. In August 2025, biotechnology company Compass Pathways published its findings on a trial designed to test the safety of psilocybin for PTSD. The small safety study wasn't designed to measure effectiveness. Nevertheless, participants seemed to show an immediate reduction in PTSD symptoms after a single 25-milligram dose of the company's synthetic psilocybin. Clinicians reported the improvements had endured when tested 12 weeks later.

In the study Averill is leading, clinicians started dosing seven participants who had experienced PTSD symptoms for an average of 19 years at the start of the trial in February. The early findings "have been incredible," Averill said during a panel discussion at the Psychedelic Science conference in Denver in June 2025.

Within a few hours of the first dose of psilocybin, every single veteran reported positive changes in their beliefs and perceptions. After the treatment effects subsided, participants underwent therapy and said the drug enabled them to reevaluate their original traumatic experiences from a nonjudgmental perspective, without the shame and guilt, Averill said.

So how does psilocybin bring about these changes?

Studies in mice have demonstrated that, in a similar vein to MDMA, psilocybin helps brain cells grow new dendritic spines. These new branches appear in the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus, the key regions responsible for learning, planning and memory.

But brain scans from people have shown that psilocybin simultaneously disrupts and desynchronizes, or dissolves, connectivity within the DMN for three weeks. Scientists hypothesize that this desynchronization of the brain system involved in self-referential processing results in a mind that is less constrained, more flexible and less consumed by self-reproach. They propose that the disruption of rigid cognitive patterns and negative thought loops may promote psychological flexibility and self-compassion.

"It has been surprising to see these maladaptive beliefs shift when I'd learned that change would only come about through longer term talk therapy," Weiss said.

Dissolving rigid thinking can open up the mind to new possibilities, including the idea that the patient wasn't responsible for the original trauma, Weiss said. Weiss is currently carrying out a clinical trial examining the effect of psilocybin therapy on the cognitive beliefs related to PTSD and is witnessing participants' experiences of the treatment.

"Many are endorsing less guilt and are able to let go of the sense that they were to blame for this happening," he said.

Proceeding cautiously, with haste

When Fonzo first reviewed the data on psychedelics as a treatment option in mental health, he was excited by what he found. But he pointed out that there haven't yet been any large, controlled studies evaluating psilocybin for PTSD. The research is still in its early stages with small pilot studies or clinical trials still assessing the safety of the drug. "There needs to be a sober perspective on what the evidence does, and does not show," Fonzo said, "because these treatments aren't necessarily going to be suitable for everyone."

Fonzo believes the answer lies in the expansion of funding for clinical trials, but research in psychedelics still faces steep hurdles. Both MDMA and psilocybin are listed as Schedule I substances in the U.S. — a federal classification reserved for drugs considered to have a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use. That label makes studying them a bureaucratic nightmare, as researchers must navigate complex regulatory approvals and secure special licenses just to handle the compounds.

On top of that, every trial demands careful screening to find participants who meet the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Also, due to the profound and unmistakable psychoactive effects of psychedelics, in trials, it can be hard to hide who is and isn't getting the drug and thus create a robust placebo group.

Despite these challenges, new clinical trials are underway to explore variations in dosage, psychotherapy pairing and long-term outcomes. Weiss and his colleagues are investigating administering combinations of MDMA and psilocybin — so-called psychedelic stacking — and comparing the effectiveness of each treatment separately. "We're still learning about what is the most efficient and rapid-acting approach to helping people," Weiss said.

For veterans who are experiencing suicidal thoughts as part of their PTSD, finding interventions that spur rapid change could be key, Weiss said. Despite the compelling findings, the regulatory approval of psychedelic treatments for PTSD is moving slowly. In August 2024, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration declined to approve MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD, citing concerns over the study design and blinding procedures. Mitchell has been frustrated about the decision not to approve the treatment with guardrails, or for a subset of people who really need it.

"My own brain gets cranky when I hear people not consider PTSD a life-threatening condition — because it is," Mitchell said. In the United States in 2024, an average of 17 veterans died each day by suicide.

"That's why speed matters. We can't wait months for treatments that barely work," Mitchell said.

Averill has witnessed PTSD patients liberated by psychedelic therapy, but she cautioned that the psychedelic experience is not a "silver bullet" but rather one that opens the doors to healing. One veteran in the clinical trial she'd been leading described feeling like he'd been locked in a cage and said every movement felt painful. The psilocybin removed the cage, and he was able to revisit his traumatic experiences.

Averill's goal is to continue exploring how psychedelic-assisted therapy can help PTSD sufferers move beyond merely tolerating their existence. "We want to help people move forward and build lives they really want to be living," Averill said.

No comments:

Post a Comment