Biomarkers are useless; they DO NOTHING to get survivors recovered! Are you that fucking clueless about stroke recovery? And you mentors and senior researchers are just as bad?

Neuroimaging and biological markers of different paretic hand outcomes after stroke

Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation volume 22, Article number: 150 (2025)

Abstract

Background

Hand dysfunction significantly affects independence after stroke, with outcomes varying across individuals. Exploring biomarkers associated with the paretic hand can improve the prognosis and guide personalized rehabilitation. However, whether biomarkers derived from resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) can effectively classify and predict different hand outcomes and their biological mechanisms remain unclear.

Methods

This study analyzed 65 patients with chronic subcortical stroke, including 32 patients with partially paretic hand (PPH) and 33 patients with completely paretic hand (CPH). For patients with PPH and CPH respectively, the age was 56.19 ± 10.53 and 55.60 ± 9.00 years, disease duration was 15.31 ± 14.87 and 14.12 ± 17.36 months, lesion volume was 9.45 ± 5.57 and 16.00 ± 11.33 ml, Fugl-Meyer Assessment for Hand and Wrist (FMA-HW) was 11.25 ± 6.15 and 1.24 ± 1.22. Four rs-fMRI metrics were analyzed, including amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF), regional homogeneity (ReHo), degree centrality (DC), and voxel-mirrored homotopic connectivity (VMHC). Multivariate pattern analysis was used to classify and predict paretic hand performance. To explore the biological mechanisms of neuroimaging biomarkers, partial least squares regression was conducted to associate gene expression data (from Allen Human Brain Atlas), neurotransmitter maps, neuron types and developmental stages with the classification weight maps of rs-fMRI metrics.

Results

ALFF achieved a higher classification accuracy of 0.88 in differentiating PPH from CPH, outperforming the other three rs-fMRI metrics. Machine learning further identified the top contributing regions from the ALFF classification weight maps, such as the ipsilesional precentral gyrus, contralesional cerebellum posterior lobe, and ipsilesional parietal lobule. Neuroimaging-transcriptome analysis revealed that macroscopic biomarkers from the ALFF were associated with the G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway and the detection of chemical stimuli involved in sensory perception. Additionally, these neuroimaging biomarkers from ALFF showed prominent expression in astrocytes and early fetal stages. Most importantly, the neurotransmitter noradrenaline positively correlated with the distribution of ALFF biomarkers.

Conclusions

The ALFF is an effective macroscopic biomarker for classifying and predicting paretic hand outcomes in individuals following chronic stroke. These neuroimaging biomarkers correspond to molecular transcriptional profiles and neurotransmitter distributions, offering insights into the potential of personalized stroke rehabilitation.

Background

Neuroimaging studies have greatly advanced our understanding of the mechanisms of behavioral deficits, spontaneous recovery, and rehabilitation strategies following stroke [1]. Specifically, motor outcomes after stroke have been linked to factors such as lesion anatomical location [2, 3], gray matter plasticity [4], corticospinal tract integrity [5], brain network connectivity [6,7,8,9,10], and regional oscillations [11]. However, the diagnosis and assessment of paretic hand function remains highly subjective and heterogeneous, relying heavily on clinical scales [12]. Given the importance of hand function for stroke survivors to regain independence, it is urgent to establish objective biomarkers of different hand outcomes to help clinicians optimize and tailor rehabilitation programs more effectively [13].

Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) allows the evaluation of intrinsic and spontaneous brain activity without the cooperation of patients with hemiparesis [10, 14]. Various functional reorganizations after stroke have been identified using rs-fMRI. For instance, after motor imagery intervention, stroke patients show an increased fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF, measuring the strength of spontaneous brain activity within a specific frequency range) within the ipsilesional inferior parietal lobule, which is associated with paretic upper extremity improvement [15]. Using degree centrality (DC, evaluating the importance of a node within the brain network based on its connection numbers), one rs-fMRI study revealed a positive correlation between ipsilesional cerebellar lobule X and lower extremity function post stroke [16]. Additionally, our previous studies demonstrated that altered voxel-mirrored homotopic connectivity (VMHC, reflecting the coordination of bilateral homotopic brain regions) and frequency-specific regional homogeneity (ReHo, assessing the synchrony of neural activity among neighboring voxels) were notably associated with paretic hand function in patients with chronic subcortical stroke [11, 17]. These studies suggest that functional brain reorganization revealed by the ALFF, ReHo, DC, and VMHC metrics may serve as potential neuroimaging biomarkers for diagnosing and assessing hand deficits after stroke.

The discovery of biomarkers has shifted to machine learning, which decodes individual behavioral phenotypes by excavating neuroimaging data from stroke patients [18]. For example, two fMRI-based support vector machine (SVM) studies could accurately classify different hand deficits and predict functional recovery following stroke [19], particularly in patients with moderate impairment and high outcome variability [20]. Using brain volumes with clinical variables, the accuracy of predicting motor recovery and 90 days outcomes was improved in patients with acute infarctions [21]. Siegel et al. demonstrated that lesion topography predicted motor impairment more accurately than functional connectivity [2]. Based on structural connectomes, Koch et al. predicted the natural recovery of individuals 2 weeks post stroke, particularly in patients with severe deficits [22]. A recent review highlighted the potential of artificial intelligence to promote the development of personalized rehabilitation following stroke [23]. These findings support the hypothesis that structural and functional neuroimaging biomarkers are useful in evaluating motor outcomes or recovery after stroke. However, it remains unclear whether a single rs-fMRI metric (such as ALFF, ReHo, DC, and VMHC) can effectively classify and predict different paretic hand outcomes.

It is well known that genetic variants and biological processes influence neuroplasticity after brain disorders, thereby contributing to behavioral deficits. By integrating transcriptome [24] and chemoarchitecture [25] datasets of the human brain, researchers can gain insights into the microscale substrates underlying macroscopic neuroimaging findings. For example, cortical thickness and myelination related to human neurodevelopment are concentrated in densely connected hubs, which are associated with gene expression in synaptic and myelin processes [26]. In patients with Alzheimer’s disease, imaging biomarkers are linked to energy metabolism and mitochondrial structure [27]. Furthermore, altered cortical thickness in patients with major depressive disorder [28], consistently abnormal VMHC in patients with schizophrenia [29], and dynamic connectome changes in patients with autism spectrum disorder [30] have been linked to specific neurobiological processes and cell types. Despite these advances, no study has investigated the relationship between hand outcomes, neuroimaging biomarkers, and biological processes in patients with chronic stroke.

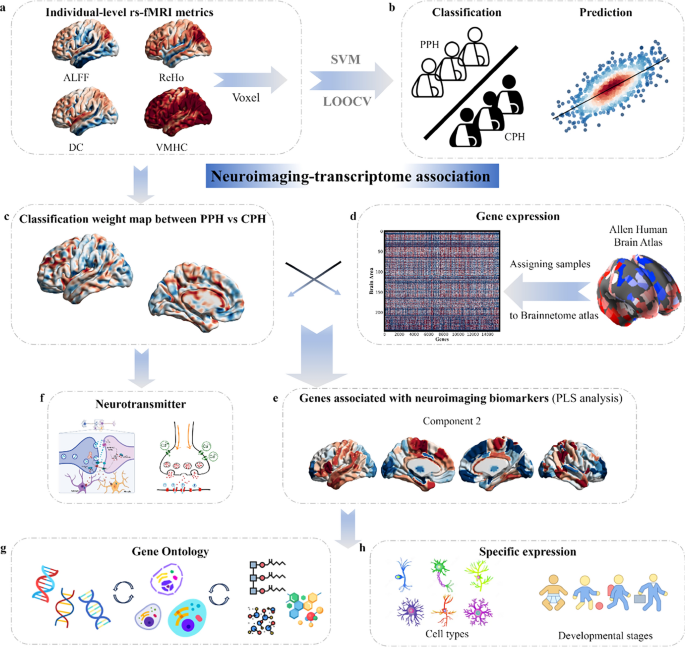

To address the gap, this study aimed to: (1) apply multivariate pattern analysis to identify which rs-fMRI metric is the best neuroimaging biomarkers for classifying and predicting different paretic hand outcomes; (2) explore ontological pathways, specific cell types, and developmental stages of genes related to neuroimaging biomarkers by conducting a functional enrichment analysis; and (3) associate neurotransmitter distribution with neuroimaging biomarkers to further uncover their roles in paretic hand outcomes. For more details, please refer to the schematic workflow (Fig. 1). In summary, this study systematically investigated neuroimaging biomarkers and their potential biological basis in chronic stroke patients with varying hand outcomes.

Workflow of the study design. a. Rs-fMRI metrics, including ALFF, ReHo, DC, and VMHC, were calculated. b. Multivariate pattern analysis was applied to classify patients with PPH and CPH and to predict individual FMA-HW scores. c. Classification weight maps with the best performance in differentiating PPH from CPH were used for further analyses. d. Gene expression profiles from the Brainnetome Atlas of 233 regions were averaged across six postmortem brains. e. PLS regression was used to identify imaging-transcriptomic associations. f–h. Neurotransmitters, gene ontology terms, specific cell types, and developmental stages were linked to identified neuroimaging biomarkers

Methods

Participants

This study was approved by the hospital’s ethics committee (2014 Interim Review No. 279) and carried out in strict accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to enrollment, the participants were provided with detailed information about the study and signed written informed consent forms. Sixty-five patients with chronic stroke were included based on the following criteria: (1) first‐episode stroke with a lesion primarily located in the left subcortical nuclei (e.g., basal ganglia or thalamus); (2) age between thirty and eighty years; (3) disease duration of at least 3 months; (4) upper limb and hand motor impairments; and (5) right-handedness, as determined by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory. Patients were excluded if they had MRI contraindications, serious cognitive deficits, language impairments such as aphasia, spatial neglect, or unstable medical conditions such as multiorgan dysfunction.

Behavioral assessment and imaging acquisition

Before MRI scanning, the Paretic Hand Scale (Supporting Information) was used to classify stroke patients into two distinct subgroups: those with a partially paretic hand (PPH) and those with a completely paretic hand (CPH), following the methodologies established in our previous studies [7,8,9]. This scale was specifically developed to assess the functional capability of the hand in daily life. Patients capable of performing at least one functional task were classified into the PPH group, indicating a partially preserved hand function. Conversely, patients incapable of completing any of the tasks were assigned to the CPH group, reflecting a severe loss of hand function. The Fugl-Meyer Assessment in Hand and Wrist subscale (FMA-HW), considered as the primary assessment tool, includes a wrist section (five items) and a hand section (seven items), with a total score range of 0–24, was used to evaluate the performance of paretic hand.

Imaging data were acquired using a 3‐Tesla SIEMENS Trio scanner (Germany). T1‐weighted images were obtained with an MPRAGE sequence, which included 192 sagittal slices, 1 mm slice thickness, 0.5 mm gap, repetition time/echo time/inversion time of 1900/3.42/900 ms, a 240 × 240 field of view, a 9° flip angle, and a 256 × 256 matrix size. T2‐weighted images were captured using a TSE sequence with 30 axial slices, 5 mm slice thickness, no gap, repetition time/echo time of 6000/93 ms, a 220 × 220 field of view, a 120° flip angle, and a 320 × 320 matrix size. Rs-fMRI data were collected using an EPI sequence with 30 axial slices, 4 mm slice thickness, 0.8 mm gap, repetition time/echo time of 2000/30 ms, a 220 × 220 field of view, a 90° flip angle, a 64 × 64 matrix size, 240 volumes, and a total scanning time of 8:06 (m: ss). During the scanning process, the participants were instructed to close their eyes, stay relaxed, and minimize any movement as much as possible.

Lesion mapping analysis

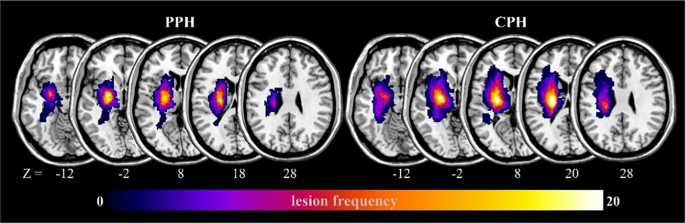

Using MRIcron (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mricron), two physicians manually outlined the lesion contours for each stroke patient based on T2-weighted images. Subsequently, the lesion masks of all stroke patients were normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute space and resampled to a resolution of 1 × 1 × 1 mm3. Finally, these resampled masks were added to create lesion maps for the patients with PPH and CPH (Fig. 2).

Analysis of brain imaging data

The rs-fMRI data were preprocessed using DPABI (https://rfmri.org/DPABI) [31] in accordance with the following steps: (1) exclusion of the first ten time points; (2) correction for slice timing; (3) adjustment for head motion; (4) co-registration of T1-weighted images with functional images; (5) segmentation and normalization to Montreal Neurological Institute space using DARTEL; and (6) removal of nuisance covariates, including Friston 24, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. The global signal was also regressed to enhance the detection of local brain activity by reducing noise and to help standardize the data across studies.

Subsequently, rs-fMRI metrics, including ALFF, ReHo, DC, and VMHC, were calculated using the DPABI. After further smoothing and detrending, standardized ALFF maps were generated to capture the intensity of local neural oscillations. After further detrending and filtering (0.01–0.08 Hz), the ReHo and binary DC maps were generated and transformed into Z-scores. Then, the Z-transformed ReHo and DC maps were smoothed with a 6 mm Gaussian kernel. The ReHo was computed using Kendall’s coefficient of concordance between a voxel and its 26 neighboring voxels, reflecting regional brain activity. DC was calculated by counting the direct connections (edges) linked to each node, where an edge was defined as a Pearson correlation coefficient of r ≥ 0.25. This threshold was selected based on previous studies and empirical assessments to balance network sparsity and meaningful connectivity [32]. After further smoothing, detrending, and filtering (0.01–0.08 Hz), the VMHC maps were generated and transformed to Z-scores, which allowed for the evaluation of homotopic connectivity across hemispheres. All participants satisfied the rigorous head motion criteria, exhibiting less than 2° of maximal rotation and 2 mm of maximal translation. Three-dimensional surface rendering of all subsequent results was conducted using BrainNet Viewer (www.nitrc.org/projects/bnv/) [33].

Statistical analyses

The baseline data for all participants were processed using SPSS software (version 25.0, IBM Corp). Initially, the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to evaluate the normality of continuous variables, including age, illness duration, lesion volume, FMA-HW scores, and framewise displacement. The results indicated that only the age variable exhibited a normal distribution; thus, it was analyzed using a two-sample t-test. For variables that did not conform to normality, the Mann–Whitney U test was employed. Additionally, the chi-square test was applied to evaluate differences between the groups in terms of sex ratio and stroke type.

Multivariate pattern analysis

The MVPANI toolbox (https://github.com/pymnn/MVPANI) was employed to perform multivariate pattern analysis on rs-fMRI metrics [34], including ALFF, ReHo, DC, and VMHC, to differentiate PPH from CPH. In the context of rs-fMRI research, SVM is among the most widely adopted and well-generalized machine learning algorithms. Accordingly, this study applied the SVM to construct a support vector classification model for classification tasks and a support vector regression model for regression tasks.

The support vector classification model was utilized to differentiate between patients with PPH and CPH, with the respective rs-fMRI metrics from each participant serving as input features. No prior feature selection was carried out because the machine learning algorithm utilized whole-brain data to identify regions with discriminatory power, rather than relying on predefined regional selection [40]. A linear kernel was applied and the penalty coefficient was set to 1. All other hyperparameters were maintained at their default settings. Given the relatively small sample size, a leave-one-out cross-validation procedure was used to validate the classification model. During each iteration of the cross-validation, 64 participants were used to train the classifier, and the remaining participants were used as the test sample. Model performance was assessed using classification accuracy (i.e., the proportion of correctly classified subjects), sensitivity, specificity, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC).

The support vector regression model was used to predict FMA-HW scores. The respective rs-fMRI metrics from each participant served as input features, whereas the corresponding FMA-HW scores were used as target labels. A leave-one-out cross-validation strategy was implemented to ensure clear separation between the training and testing datasets. For the prediction analysis, epsilon- support vector regression with a linear kernel was employed using the default parameter settings (i.e., penalty coefficient = 1 and epsilon in the loss function = 0.1). The model performance was quantified by calculating the squared correlation coefficient (R2) between the actual and predicted values and the mean absolute error.

Permutation test and weight calculation

The statistical significance of the classification and regression models was evaluated using 1000 permutation tests by generating null distributions to assess whether the performance exceeded the chance level (50%). Additionally, a linear kernel SVM was implemented in this study, which permitted direct extraction of the model's weight vector and facilitated creation of the discrimination maps for visualization purposes. To improve the clarity of discriminative patterns, voxels with values greater than 35% of the maximum value within the discrimination maps were emphasized. By employing this empirically chosen threshold, noise components were substantially reduced, enabling distinct visualization of the brain regions most relevant for discrimination [40].

Correlation analysis between neuroimaging biomarkers and gene expression

Gene expression data sourced from the Allen Human Brain Atlas (http://human.brain-map.org) were mapped onto the Brainnetome atlas using Abagen toolbox (https://github.com/rmarkello/abagen). This mapping process resulted in a gene expression matrix covering 233 brain regions and 15,633 genes, excluding 13 regions that lacked the corresponding genes identified by Abagen. A multivariate Partial Least Squares (PLS) approach was employed to explore the relationship between brain transcriptome and neuroimaging biomarkers. Gene expression data and weight maps derived from a classification model trained to distinguish between the PPH and CPH groups were used as the predictor and response variables, respectively. In PLS models, a weight randomization test determines the optimal number of components. To assess whether the R2 of a PLS component was significantly greater than expected by chance, a spatial autocorrelation-corrected permutation test with 5000 iterations was applied. Considering the spatial autocorrelation characteristic of brain maps, the brain surrogate maps with autocorrelation spatial heterogeneity (BrainSMASH, https://github.com/murraylab/brainsmash) package was utilized to create 5000 surrogate maps that preserved spatial autocorrelation for the statistical difference maps. If a component demonstrated a significant ability to explain the variance in the response variable, a bootstrapping procedure was employed to adjust for the estimation errors in the weights assigned to each gene. The PLS gene weights were standardized into z-scores by dividing them through the standard deviation of weights obtained from 5000 bootstrap samples [26]. Genes were then ranked according to their contributions to the PLS components, with positive weights ranked in descending order and negative weights in ascending order based on z-scores. The Gorilla tool (http://cbl-gorilla.cs.technion.ac.il/) was used to perform gene enrichment analysis, covering both ascending and descending sequences, with the goal of identifying enriched gene ontology terms [35]. The P value threshold was set at 10–7, and the analysis focused on biological processes. Enrichment was deemed significant if the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) corrected q-value was less than 0.05.

Mapping neuroimaging-associated genes to specific cell types and developmental stages

The identified genes were further analyzed to detect overrepresented cell types and developmental stages [36], which encompass a diverse range of cell types, including excitatory neurons, inhibitory neurons, astrocytes, and others, spanning various developmental stages from the early fetal period to young adulthood [37]. To quantify the association between the identified genes and specific cell types, the mean absolute Z-score was calculated for the identified genes belonging to each category [38]. This analysis was performed separately for genes with positive and negative scores to distinguish between the upregulated and downregulated gene expression profiles. To evaluate the statistical significance of the observed cell type-specific scores, a permutation test with 10,000 iterations was performed for each cell type. Given that multiple cell types were tested, FDR correction for multiple comparisons was performed. The same procedure was applied to the developmental stages and the mean gene scores for each stage were calculated to assess their contributions.

Exploring correlations between neuroimaging biomarkers and neurotransmitters

To explore the relationships between neuroimaging biomarkers and chemical architecture organization, correlation analyses were conducted between weight maps derived from a classification model trained to distinguish between the PPH and CPH groups and neurotransmitter maps, as provided by the JuSpace toolbox (https://github.com/juryxy/JuSpace) [25]. The JuSpace toolbox offers a collection of various neurotransmitter transporters and receptor maps derived from positron emission tomography studies of healthy participants, including 5-hydroxytryptamine, serotonin transporter, D1 receptor, D2 receptor, dopamine transporter, vesicular acetylcholine transporter, fluorodopa, gamma-aminobutyric acid, metabotropic glutamate receptor 5, and noradrenaline transporter (NAT) [39]. Spatial correlations were subsequently calculated between the chosen neurotransmitter maps and weight maps using Spearman correlations (based on the Neuromorphometrics atlas; exact P values, N = 5000 permutations; adjusted for spatial autocorrelation). FDR correction was used to account for multiple comparisons across neurotransmitter maps.

Results

Demographic and clinical information derived from PPH versus CPH

As shown in Table 1, no significant differences were observed between the PPH and CPH groups in terms of age (P = 0.811), sex ratio (P = 0.110), stroke type (P = 0.540), illness duration (P = 0.305), or framewise displacement (P = 0.823). However, lesion volume was notably larger in patients with CPH than in those with PPH (P = 0.006), while FMA-HW scores were notably higher in the PPH group compared to the CPH group (P < 10–9).

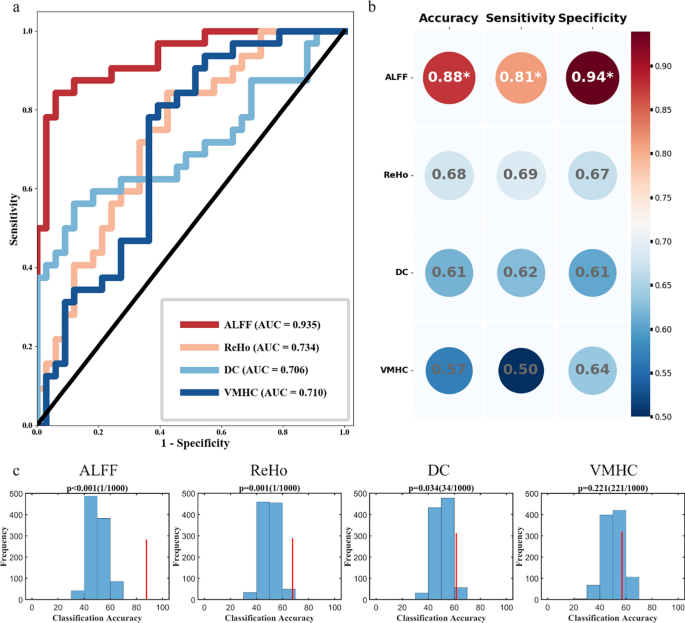

Classification performance of four rs-fMRI metrics in differentiating PPH from CPH

The classification accuracy of each metric is shown in Fig. 3: ALFF achieved the highest accuracy at 0.88, with a specificity of 0.81 and sensitivity of 0.94; ReHo yielded an accuracy of 0.68 (specificity, 0.69; sensitivity, 0.67), followed by DC at 0.61 (specificity, 0.62; sensitivity, 0.61), and VMHC at 0.57 (specificity, 0.50; sensitivity, 0.64). The corresponding AUC values were 0.935, 0.734, 0.706, and 0.710 for the ALFF, ReHo, DC, and VMHC, respectively. Among these metrics, ALFF demonstrated the strongest discriminative ability to differentiate PPH from CPH. Permutation tests further confirmed significant classification performance for ALFF (P < 0.001), ReHo (P = 0.001), and DC (P = 0.034), whereas VMHC did not reach significance (P = 0.221).

Classification performance of different paretic hand outcomes using a support vector machine. a. The receiver operating characteristic curves for each metric illustrate their performance in differentiating PPH from CPH. b. Summary of classification performance of each metric, including accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. c. The statistical significance of the classification models was evaluated using 1000 permutation tests, generating a null distribution to assess significance

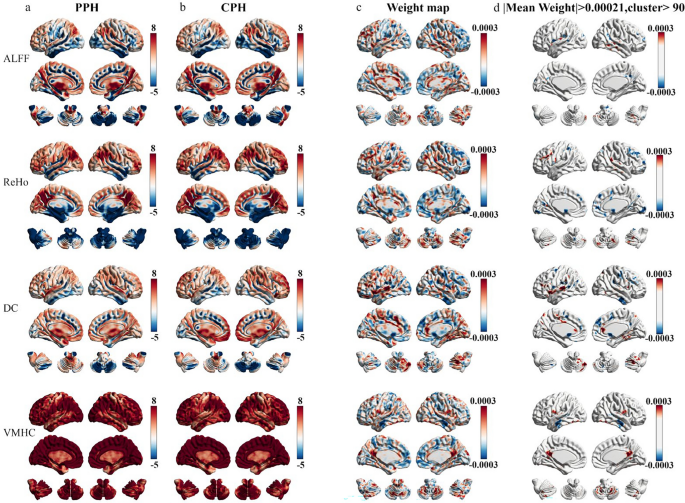

Contribution weight maps of four rs-fMRI metrics in differentiating PPH from CPH

The one-sample spatial patterns of each metric in the PPH and CPH groups along with their classification weight maps generated by the support vector classification model are shown in Fig. 4. Among all metrics, ALFF achieved the highest classification accuracy and AUC, indicating its superior discriminative capability. To further interpret the classification contributions of ALFF, we examined the corresponding feature weight maps from the support vector classification model (Fig. 4c, d). Regions with positive weights, which contributed more to identifying the PPH group, were primarily located in the contralesional (i.e., middle temporal gyrus and cerebellum posterior lobe) and ipsilesional hemispheres (i.e., insula and superior occipital lobe). In contrast, regions with negative weights, which were more informative for classifying the CPH group, were distributed in the ipsilesional precentral gyrus, ipsilesional inferior parietal lobule, contralesional middle frontal gyrus, contralesional superior temporal gyrus, and contralesional precuneus (Table 2).

Classification weight maps for different paretic hand outcomes after stroke. a, b. One-sample spatial distributions of ALFF, ReHo, DC, and VMHC in the PPH and CPH groups. c. Spatial distributions of classification weight maps for each metric. d. The thresholded classification weight maps highlight the top contribution regions for differentiating PPH from CPH

Predictive performance of rs-fMRI metrics for paretic hand function in stroke patients

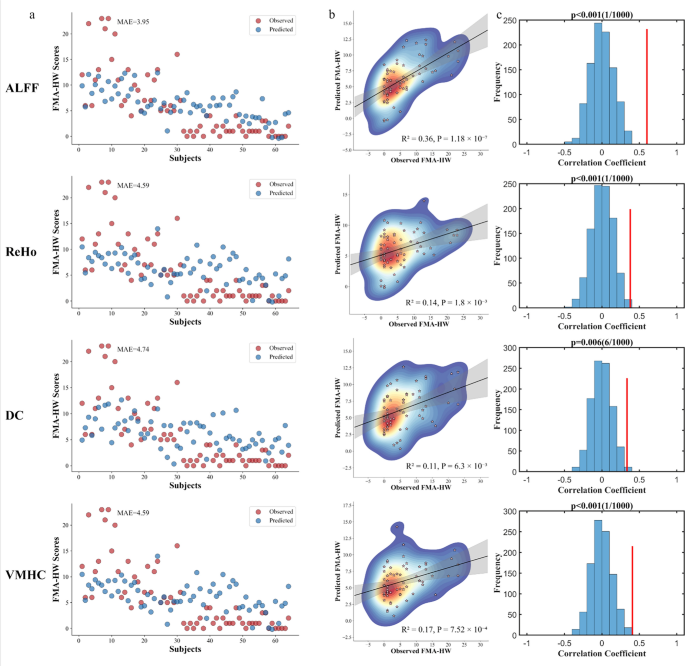

The prediction results of support vector regression demonstrated that the four rs-fMRI metrics may serve as predictors of FMA-HW scores in patients with chronic stroke (Fig. 5). ALFF achieved the highest performance (R2 = 0.36, P = 1.18 × 10⁻⁷, MAE = 3.95), followed by VMHC (R2 = 0.17, P = 7.52 × 10⁻4, MAE = 4.59), ReHo (R2 = 0.14, P = 1.80 × 10⁻3, MAE = 4.59), and DC (R2 = 0.11, P = 6.30 × 10⁻3, MAE = 4.74). Permutation tests were statistically significant for all models (P < 0.01).

Prediction performance of paretic hand scores using different rs-fMRI metrics. a. Scatter plots show the observed and predicted FMA-HW scores across subjects. The mean absolute error (MAE) is indicated for each panel. b. Scatter density plots show correlations between observed and predicted scores. The coefficient of determination (R2) and P values are displayed. c. The statistical significance of the regression models was evaluated using 1000 permutation tests, generating a null distribution to assess significance

Gene expression associated with ALFF biomarkers in differentiating PPH from CPH

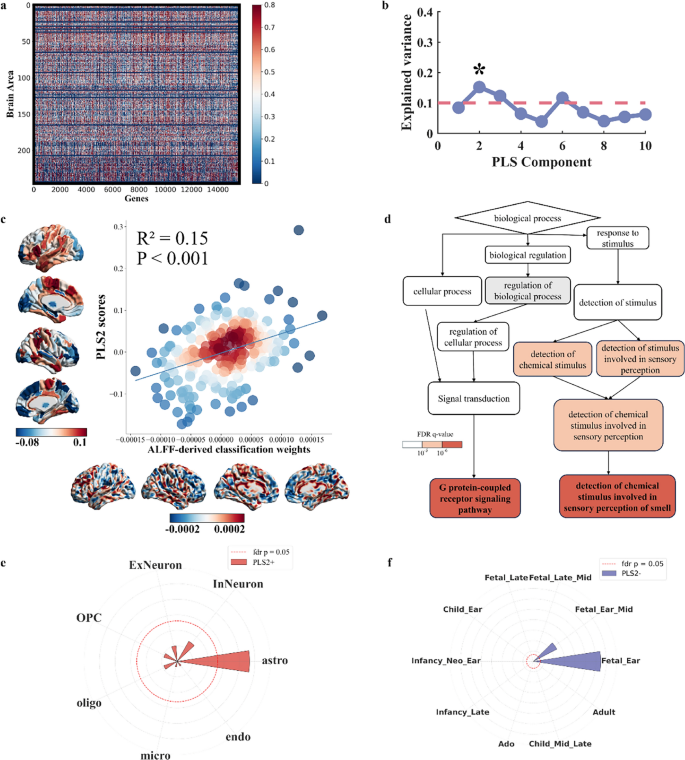

One PLS component accounted for 15.2% of the variance in the ALFF-derived classification weight maps (P = 0.02 for component 2 based on 5000 permutation tests with correction for spatial autocorrelation) (Fig. 6b). Component 2 reflected a transcriptional profile featuring high expression predominantly in the sensorimotor cortex, inferior temporal gyrus, superior frontal gyrus, and parietal gyrus. The regional distribution of this component exhibited a positive correlation with the ALFF-derived classification weight maps in differentiating PPH from CPH (Component 2: R2 = 0.15, Pperm < 0.001; based on 5000 permutation tests with spatial autocorrelation corrected, Fig. 6c). Gene Ontology enrichment analysis indicated that the genes ranked in descending order by the weight of component 2 were significantly enriched in biological processes related to the detection of chemical stimulus involved in sensory perception of smell (GO:0050911, FDR q = 0.00000112) and G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway (GO:0007186, FDR q = 0.0000000387). No significant enrichment was found for genes ranked in ascending order for component 2 (Fig. 6d). Cell-specific expression analysis revealed that PLS2 positively weighted genes were predominantly associated with astrocytes (Fig. 6e). Developmental analysis showed that PLS2 negatively weighted genes were specifically expressed during the early fetal stages (Fig. 6f).

Transcriptional profiles of ALFF-derived classification weight maps. a. A gene expression matrix was used for imaging-transcriptomic associations. b. The explained variance for each PLS component and the significant components are marked with asterisks. c. ALFF-derived classification weight maps were positively correlated with gene expression patterns. d. The gene ontology network illustrates the hierarchical organization of the biological processes associated with PLS2 in descending order. e, f. The radial plots show the associations of PLS2 + with astrocytes and PLS2- with human development during the early fetal stages

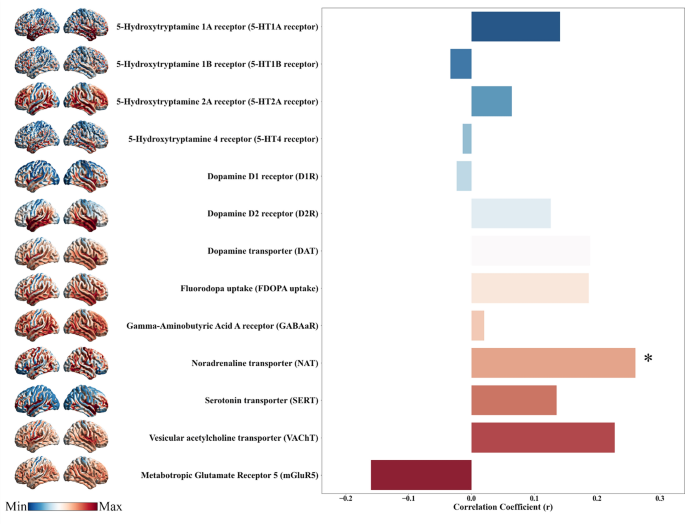

Neurotransmitters distribution related to ALFF biomarkers in differentiating PPH from CPH

To examine the neurochemical basis of macroscopic neuroimaging biomarkers, we assessed the spatial correlations between classification weight maps and 13 in vivo neurotransmitter distribution maps. Interestingly, only the ALFF-derived classification weight maps derived from PPH and CPH showed a significant positive correlation with the NAT map (R2 = 0.07, FDR P = 0.0468) (Fig. 7).

Neurotransmitter distribution correlated with ALFF-derived classification weight maps. The panel depicts the regional distributions of various neurotransmitter systems and their correlations with ALFF-derived classification weight maps for differentiating PPH from CPH. Significant correlations are indicated with asterisks

Discussion

By integrating rs-fMRI metrics, transcriptional data, and machine learning techniques, this study first uncovered neuroimaging biomarkers and their biological substrates in patient’s chronic stroke with varying paretic hand outcomes. Specifically, our study demonstrated that: (1) ALFF achieved the best performance for classifying and predicting paretic hand function in stroke survivors, highlighting its potential as a valuable neuroimaging biomarker for motor recovery and rehabilitation after stroke; and (2) specific biological processes, neuron types, developmental stages, and neurotransmitters were linked to ALFF biomarkers in differentiating PPH from CPH. In summary, our findings provide novel insights into the relationship between macroscale neuroimaging biomarkers and microscale biomechanisms in different paretic hand outcomes after chronic stroke.

ALFF as potential neuroimaging biomarkers for paretic hand function after stroke

Among the single rs-fMRI metrics, ALFF demonstrated superior performance compared with ReHo, DC, and VMHC. This finding is consistent with that of a previous study [40], which demonstrated that ALFF-based models offer better classification accuracy in diagnosing obsessive–compulsive disorder. The superiority of the ALFF metric may be attributed to its robust correlations with spontaneous neural activity and regional glucose metabolism [41], making it more sensitive for detecting brain disorders. In light of these findings, our results indicate that ALFF could serve as a potential neuroimaging biomarker to support the development of future decision models for personalized neurorehabilitation.

Brain reorganizations underlying different hand outcomes after stroke

We found that specific non-motor regions (such as the middle frontal gyrus, middle/inferior temporal gyrus, insula, and occipital lobe) critically contributed to the classification and prediction of paretic hand performance. Stroke patients with motor impairments often exhibit reorganization in non-motor regions [7,8,9, 17]. Heightened activation of these non-motor areas is widely associated with less favorable motor outcomes [42]. Movement-related activation in the middle frontal gyrus has been linked to cognitive motor interference after stroke [43]. Resting-state functional connectivity analysis revealed that stronger coupling between the ipsilesional premotor cortex and contralesional middle frontal gyrus is a predictor of long-term motor outcomes following stroke [6]. Complex motor tasks frequently rely on audiomotor cooperation, with the bilateral temporal gyrus being the primary region involved in this process [44]. A longitudinal task-based fMRI study revealed that a reduction in temporal cortex recruitment over time was associated with motor recovery following stroke [45]. Additionally, early contralesional insula activation [46] and increased cortical thickness in the occipital region have been linked to sensorimotor function after stroke [47]. Theta-band activity (4–8 Hz) predominates the default mode network, supporting neural reinstatement mediated by theta and high-gamma oscillations in the middle temporal gyrus [48]. The insula within the salience network suppresses default mode activity during motor tasks and the middle frontal gyrus anchored in the executive control network exerts top-down inhibitory control over the default mode network [49]. Given the roles of these non-motor regions in the default mode, executive control, and salience networks, our findings indicate that impaired inhibitory and shift processing between the sensorimotor and these networks may damage the fine motor ability of the paretic hand in patients with chronic stroke.

Most importantly, we found that the precentral gyrus, cerebellum posterior lobe, and inferior parietal lobule also play significant roles in classifying and predicting paretic hand performance. Functional reorganization of the ipsilesional precentral gyrus has consistently been associated with motor recovery in both task-based and resting-state fMRI studies [7, 50]. A previous rs-fMRI study demonstrated that functional connectivity between the contralesional M1 and occipital cortex was decreased in stroke patients [6]. Enhanced alpha and beta event-related desynchronization within the ipsilesional motor cortex during paretic limb movement at 1.5 months post stroke correlates with motor deficits [51]. Additionally, increased activation in the contralesional anterior cerebellum 20 days post stroke has been positively correlated with improved finger tapping performance [52]. Our previous findings indicated that VMHC of the posterior cerebellar lobe is a robust predictor of paretic hand performance in patients with chronic stroke [17]. Furthermore, associative cortices such as the inferior parietal lobule have been linked to impaired hand function during the chronic phase of stroke [9]. Therefore, the cortico-ponto-cerebellar circuit, which integrates the precentral gyrus, cerebellum posterior lobe, and inferior parietal lobule for motor control and perception feedback [53], could be considered a promising target for non-invasive brain stimulation to facilitate neuroplasticity and optimize rehabilitation outcomes.

Transcriptional profiles of neuroimaging biomarkers for different hand outcomes after stroke

We found that the neuroimaging biomarkers derived from the PPH and CPH classification were primarily associated with the G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway and the detection of chemical stimulus involved in sensory perception. Voltage-dependent modulation of G protein-coupled receptors plays a crucial role in neuroplasticity, and this mechanism may be leveraged in stroke recovery to enhance functional reorganization [54]. Given the well-characterized features of G protein-coupled receptor signaling in sensory systems, including high sensitivity, rapid activation, and amplification, it is plausible that similar mechanisms may contribute to experience-dependent plasticity in stroke, although this remains to be elucidated [55]. Regarding neuronal cell types, we found that PLS2 positively weighted genes were enriched in astrocytes. Astrocytes, the predominant glial cells in the central nervous system, are key regulators of excitatory synaptic transmission [56]. Thus, astrocytes are closely linked to neuroplasticity and sensorimotor recovery following stroke [57]. Additionally, developmental set enrichment analysis indicated that these PLS2 negatively weighted genes were enriched during the early fetal period, suggesting that susceptibility to stroke might originate early in life. However, experimental validation is required to confirm the role of these biological markers in stroke pathology and recovery.

Neurotransmitter may influence neuroplasticity and motor outcomes after stroke

Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers that facilitate information processing across the central nervous system and maintain normal brain functions [58]. We observed a positive correlation between the ALFF-derived classification weight maps derived from PPH versus CPH and NAT. This finding is consistent with that of a human study, suggesting that noradrenergic stimulation through reboxetine improved paretic hand performance by modulating motor network connectivity in patients with stroke [59]. Mutations and dysregulation of NAT have been linked to various neurological disorders, highlighting NAT as a potential therapeutic target [60]. While our results suggest a potential association between the neurotransmitter system and motor outcomes following stroke, it is important to emphasize that these findings reflect only correlations but not causal mechanisms. Thus, a more cautious interpretation is warranted, and further empirical studies are required to validate these observations.

Limitations

First, the strict criteria for participants resulted in a relatively small sample size; thus, the statistical power may be reduced by this limitation, potentially restricting the generalizability of our findings to more diverse populations. Second, this study relies on PLS and spatial association analyses, which identify correlations, but do not establish causality. Further studies are required to validate these causal relationships. Third, the Allen Human Brain Atlas data were obtained from different measurements of six participants who were not diagnosed with stroke, which limits cross-group studies of neuroimaging–transcriptome associations. Further validation, based on gene expression and imaging data from the same cohort, is necessary. Fourth, the recruited patients had a wide range of disease courses, which may have affected our findings slightly. However, spontaneous recovery usually reaches a plateau approximately 6 months after stroke [61]. Thus, most of our samples with disease durations beyond 6 months can lead to stable brain functional reorganization [1, 62]. Finally, the complex relationships between pathophysiological processes and brain plasticity remain unclear, and future research should integrate longitudinally macroscopic and microscopic markers to better understand their roles in stroke rehabilitation.

Conclusions

This study identified neuroimaging biomarkers associated with different paretic hand outcomes and explored their potential biological underpinnings. These results provide preliminary evidence that neuroimaging biomarkers serve as translational bridges connecting molecular pathophysiology to clinically functional outcomes, potentially reshaping precision rehabilitation in stroke care.

No comments:

Post a Comment