Your doctor should have already checked and corrected your gut microbiome for stroke recovery already so this doesn't lead to Parkinsons. But that assumes your doctor is competent. Good luck with that.

Your doctor should be up-to-date on all things gut microbiome/microbiota for your stroke recovery already. If not, you don't have a functioning stroke doctor! Why the hell are you seeing and paying them?

gut microbiome (28 posts to May 2016)

gut microbiota (24 posts to June 2016)

Gut microbiome dysbiosis across early Parkinson’s disease, REM sleep behavior disorder and their first-degree relatives

Nature Communications volume 14, Article number: 2501 (2023)

Abstract

The microbiota-gut-brain axis has been suggested to play an important role in Parkinson’s disease (PD). Here we performed a cross-sectional study to profile gut microbiota across early PD, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), first-degree relatives of RBD (RBD-FDR), and healthy controls, which could reflect the gut-brain staging model of PD. We show gut microbiota compositions are significantly altered in early PD and RBD compared with control and RBD-FDR. Depletion of butyrate-producing bacteria and enrichment of pro-inflammatory Collinsella have already emerged in RBD and RBD-FDR after controlling potential confounders including antidepressants, osmotic laxatives, and bowel movement frequency. Random forest modelling identifies 12 microbial markers that are effective to distinguish RBD from control. These findings suggest that PD-like gut dysbiosis occurs at the prodromal stages of PD when RBD develops and starts to emerge in the younger RBD-FDR subjects. The study will have etiological and diagnostic implications.

Introduction

Alpha-synucleinopathies, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD), are characterized by the abnormal aggregation of alpha-synuclein (α-syn) protein in the central nervous system (CNS)1,2. However, increasing evidences suggested that α-syn pathology has already occurred in the enteric nervous system (ENS) prior to the involvement of CNS3,4, which strongly supported the gut-to-brain propagation of α-synucleinopathy as proposed in refs. 2,5. In parallel, gut microbiota disturbance (gut dysbiosis), an emerging biomarker and intervention target for various complex diseases, has been consistently reported in PD patients6. It was hypothesized that PD-associated gut dysbiosis, especially the depletion of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA)-producing bacteria7,8,9 and enrichment of putative pathobionts10, was related to intestinal hyperpermeability11, immune activation12, and pathological α-syn aggregation11,13. Nonetheless, given that enteric α-syn pathology and ENS dysfunctions especially constipation could occur decades before the onset of PD3,14, it is critical to understand gut microbiota and host–microbiome interactions at much earlier prodromal stages of PD before evident motor symptoms develop.

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is perceived as the most specific prodromal marker of PD, characterized by dream-enactment behaviors and REM sleep without atonia15. Patients with video-polysomnography (v-PSG)-confirmed RBD reported an increased prevalence of constipation16, and increased phosphorylated α-syn immunostaining in ENS4. Likewise, PD patients with premotor RBD features appeared to exhibit prominent degeneration of the peripheral nervous system (e.g., increased constipation and enteric α-syn histopathology) when comparing to those without, suggesting a distinct subtype of Parkinson’s disease that reflects the gut-brain hypothesis of α-synucleinopathy17. On the other hand, isolated RBD symptoms, but not yet meeting the v-PSG diagnostic criteria for RBD, might reflect a prodromal stage of RBD and the early presentation of α-synucleinopathy18,19. A recent case–control–family study reported that the first-degree relatives of RBD (RBD-FDR) had increased constipation and a spectrum of RBD features: from isolated RBD symptoms (indicative of prodromal RBD) to v-PSG-diagnosed RBD. Therefore, RBD-FDR might harbor a group of susceptible individuals at a much earlier stage of α-synucleinopathy than RBD patients20.

Prior studies have reported gut microbiota dysbiosis in v-PSG diagnosed RBD (n = 21 and 26, respectively)21,22 and possible RBD as assessed by screen questionnaire (n = 84)23. However, although these prior studies suggested a similar trend of changes in microbial composition in RBD and PD, they might be underpowered to comprehensively detect host–microbiome interactions. In addition, a prodromal stage of RBD has been increasingly recognized24, underscoring the importance of studying gut microbiota at an even earlier prodromal stage. Here, we performed a large cross-sectional study across prodromal and early stages of disease (i.e., simulate the Braak staging model with a quasi-longitudinal design)2, to disentangle the associations of gut microbiota with the progression of α-synucleinopathy.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

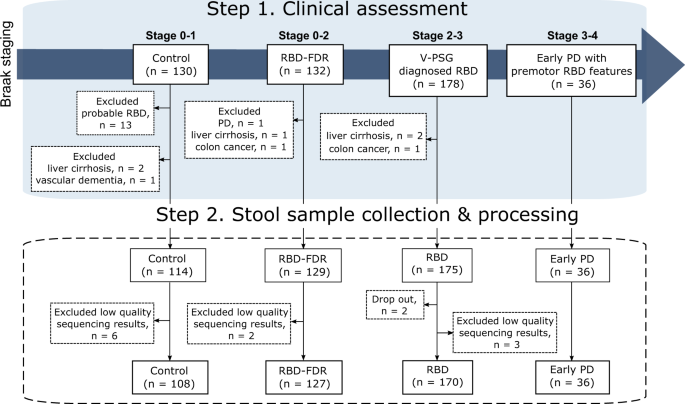

This study includes stool samples from 452 subjects from the cohorts of v-PSG-diagnosed RBD and RBD family in Hong Kong. After excluding 11 samples with low read count, a total of 441 samples remained for further analyses (Fig. 1). All patients with early PD had clinically confirmed PD with motor symptoms onset less than 5 years. Control (n = 108, 67.3 ± 7.0 years, 63.9% males) were age- and sex-matched with RBD (n = 170, 68.6 ± 7.6 years, 73.5% males) and early PD groups (n = 36, 67.8 ± 5.6 years, 86.1% males). All three groups were older with more males when comparing to RBD-FDR (n = 127, q values <0.05). The severity of RBD features, as captured by RBDQ-HK questionnaire, was significantly increased from control, RBD-FDR to RBD and early PD (total score of RBDQ-HK, 6.3 ± 7.0 vs 9.2 ± 8.4 vs 39.2 ± 17.7 vs 32.8 ± 16.1, P value <0.001). Of 127 RBD-FDR, 11 (8.7%) were diagnosed with probable RBD based on a structured clinical interview25. Total likelihood ratio (LR) for prodromal PD is a research criterion used to identify subjects at risk of having prodromal PD. We found that RBD patients had greater LR of prodromal PD (excluding RBD item) than control (log-transformed LR, 1.4 ± 0.98 vs 0.58 ± 0.72, q value <0.001) and RBD-FDR (1.4 ± 0.98 vs 0.46 ± 0.55, q value <0.001), while control and RBD-FDR had comparable levels of total LR (Supplementary Dataset 1).

We recruited subjects according to the proposed staging model of α-synucleinopathy, which aptly represented the pathological staging of Parkinson’s disease (i.e., Braak staging). Four different clinical stages were controls (Braak stage 0–1), RBD-FDR (stage 0–2), patients with RBD (stage 2–3) and early PD (stage 3–4). Early PD refers to patients who had clinically confirmed PD with motor symptoms onset less than 5 years. Control subjects with probable RBD as diagnosed by using structured clinical interview were excluded. Besides, subjects with neurodegenerative diseases (except early PD group) and severe gastrointestinal diseases were excluded from this study. In the end, a total of 452 subjects successfully collected stool samples, while 11 of them were removed for subsequent analysis due to the low quality of sequencing data (i.e., total read count <1000). RBD REM sleep behavior disorder, RBD-FDR first-degree relatives of patients with RBD, PD Parkinson’s disease.

Gastrointestinal symptoms were assessed by the Rome-IV diagnostic questionnaire for adults and Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease—Autonomic26,27. The prevalence of functional constipation showed an increasing trend from control, RBD-FDR, RBD to early PD patients (8.3 vs 9.4 vs 45.3 vs 69.4%, P value <0.001). Straining with defecation, a core feature of functional constipation, progressively increased across four groups even after adjusting age and sex (8.8 vs 15.8 vs 45.4 vs 68.6%, P value <0.001). Besides, we used bowel movement frequency score [BMF, ranges from 1 (“bowel movement >1/day”) to 6 (“≤1/week”)] and stool consistency (inverse scoring of the Bristol Stool Form Scale [BSFS], with higher scores indicating harder stools) as the proxies for colon transit time, both of which demonstrated increasing trends across the four groups (P values <0.001). Other gastrointestinal disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome and functional diarrhea, did not differ among the groups.

In terms of clinical characteristics, RBD patients reported more lifetime major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders than control and RBD-FDR (all q values <0.05)28. Other potential confounding human diseases, such as diabetes and dyslipidemia, were similarly distributed among four groups. Medication usage referred to any drugs taken during the period of stool collection. It was found that more than half of the RBD and early PD patients took benzodiazepines, while 30.6% and 13.9% of early PD patients and 5.3% and 25.3% of RBD patients were taking osmotic laxatives and antidepressants, respectively. As for PD-specific drugs, 47.2% early PD patients received carbidopa/levodopa, followed by monoamine oxidase B inhibitors (41.7%), dopamine agonist (8.3%), benzhexol hydrochloride (5.6%), and catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors (2.8%). Lifestyle features, including pre-/probiotics consumption and subjective physical activity, showed no significant differences between groups (Supplementary Dataset 1).

More at link.

No comments:

Post a Comment