You ABSOLUTE BLITHERING IDIOTS! Survivors don't want you predicting lack of social integration! You create protocols that get them there, most likely 100% recovery protocols! Don't understand that? Get the hell out of stroke and do some basket weaving!

Predictors of social risk for post-ischemic stroke reintegration

Scientific Reports volume 14, Article number: 10110 (2024)

Abstract

After stroke rehabilitation, patients need to reintegrate back into their daily life, workplace and society. Reintegration involves complex processes depending on age, sex, stroke severity, cognitive, physical, as well as socioeconomic factors that impact long-term outcomes post-stroke. Moreover, post-stroke quality of life can be impacted by social risks of inadequate family, social, economic, housing and other supports needed by the patients. Social risks and barriers to successful reintegration are poorly understood yet critical for informing clinical or social interventions. Therefore, the aim of this work is to predict social risk at rehabilitation discharge using sociodemographic and clinical variables at rehabilitation admission and identify factors that contribute to this risk. A Gradient Boosting modelling methodology based on decision trees was applied to a Catalan 217-patient cohort of mostly young (mean age 52.7), male (66.4%), ischemic stroke survivors. The modelling task was to predict an individual’s social risk upon discharge from rehabilitation based on 16 different demographic, diagnostic and social risk variables (family support, social support, economic status, cohabitation and home accessibility at admission). To correct for imbalance in patient sample numbers with high and low-risk levels (prediction target), five different datasets were prepared by varying the data subsampling methodology. For each of the five datasets a prediction model was trained and the analysis involves a comparison across these models. The training and validation results indicated that the models corrected for prediction target imbalance have similarly good performance (AUC 0.831–0.843) and validation (AUC 0.881 - 0.909). Furthermore, predictor variable importance ranked social support and economic status as the most important variables with the greatest contribution to social risk prediction, however, sex and age had a lesser, but still important, contribution. Due to the complex and multifactorial nature of social risk, factors in combination, including social support and economic status, drive social risk for individuals.

Introduction

Following post-stroke rehabilitation, the long-term patient outcome generally encompasses reintegration into normal activities of daily living in the home, community, and workplace1,2,3. An essential part of this process is community integration, which includes relationships with others, the ability to be independent in daily life activities (ADL), and participation in meaningful events4,5,6. There is consistent evidence that continued positive interaction with one’s proximate social environment (e.g., family, friends and work life) exerts beneficial effects on health and well-being, increasing resilience to unexpected setbacks7,8. Conversely, social isolation or lack of close social ties is associated with poor health and increased mortality risk9,10. Complementary to community integration is minimizing social risk, which is a complex and multifactorial phenomenon that can vary significantly for an individual, but generally encompasses environmental, socioeconomic, as well as family and social support factors11,12,13. For example, a patient with insufficient family support who is unable to access social support, such as home health care or a day center, is at a greater risk of poorer quality of life during reintegration, social isolation, and retreat from life (also termed fragility). These considerations emphasize the importance of quality of life, social well-being, as well as adequate support for patients with social risks during long-term reintegration14,15.

Several studies in the literature highlight the importance of family support in the context of the social environment (also termed sociofamiliar) and the socioeconomic situation in the overall rehabilitation outcome and reintegration of patients16,17,18,19. Although these studies target a broader patient population with physical, cognitive and sensory disturbances which include stroke patients, as well as elderly patients and their likelihood of discharge from a geriatric unit centre, nevertheless sociofamiliar factors play a significant role in the resilience of most patient populations. Ramírez-Duque et al. analyzed the clinical, functional, cognitive, sociofamiliar, and other characteristics of pluripathological patients and found that older people with cognitive and more severe functional impairment had worse sociofamiliar support than other patient groups18. In a similarly comprehensive study of the clinical, functional and social risk profiles of the elderly in a community in Lima, Peru, Varela-Pinedo et al. found that 8% of individuals lived alone, and nearly 60% had inadequate socioeconomic support and were at social risk19. In another study, Cahuana-Cuentas Milagros et al. concluded that family and socioeconomic factors have a significant impact on the levels of resilience of people with physical and sensory disabilities17. Finally, Sabartés et al. identified a deteriorated social situation as the only significant predictor of being institutionalized rather than discharged home for a cohort of hospitalized elderly patients16.

Since family, social and economic factors have been identified as having a significant impact on the quality of life of patients post-rehabilitation, the key goals of post-stroke reintegration have focused on improving patient outcomes across these factors, as well as designing personalized interventions for patients with social risk20. More recently, special situations, such as the pandemic, have added additional uncertainties and strains to the recovery and reintegration process of patients21,22,23. Therefore, it is essential for both the patients as well as clinicians to be able to forecast the level of dependence on social supports (the level of social risk) for an individual patient at admission to rehabilitation so that the necessary interventions can be put in place during rehabilitation in order to prevent setbacks after discharge. Due to the complexity of reintegration, encompassing the spatiotemporal component (long-term processes taking place in the home, community, and workplace)24, multifactorial component (interdependency of psychosocial, environmental, and socioeconomic factors) as well as demographic and cultural factors (younger age, gender, geographic location)25,26,27,28,29, predictive modelling of social risk is an invaluable tool in not only forecasting the level of social risk for an individual but also identifying the contributing factors to this risk. Accurate predictions of factors contributing to social risk can allow rehabilitation professionals (social workers, physical therapists, neuropsychogists, psychologists, etc.) to support persons with personalized interventions, prevent fragility, as well as help improve patients’ quality of life and support their specific clinical needs and challenges throughout the reintegration process. For this purpose, machine learning (ML) algorithms and statistical analyses have been employed in recent years to develop predictive models for stroke reintegration, such as in the case of long-term trajectories of community integration30,31, and functional and cognitive improvement during rehabilitation32,33. However, predictive modelling for social risk utilizing ML methodology has been a largely underexplored topic34. Cisek, et al. focused on various conceptualizations of social risk during post-stroke reintegration, such as the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) framework, as well as utilizing data visualization to explore the cohort35. In this work, we go beyond data exploration and understanding to predictive modeling and apply machine learning to develop interpretable predictive models that provide individualized predictions to guide personalized interventions for patients with social risk.

Methodology

Social risk questionnaire

Social workers conduct an interview at admission and discharge from the rehabilitation hospital following a structured questionnaire to assess social risk of patients, called “Escala de Valoracion Socio Familiar” (EVSF; eng. trans.: sociofamiliar assessment scale)35. The questionnaire is based on the Gijon sociofamiliar scale36 that includes five items (housing, family situation, economic situation, relationships, and social support). Accordingly, the EVSF questionnaire consists of five items also termed dimensions: cohabitation, economic status (indicating income sufficiency), home status (indicating home accessibility in case of mobility problems), family support and social support (Table 1). Each of these five items has five levels of risk that are scored from 1 to 5. A higher score for each item represents a higher risk for the social reintegration of the patient. The total score is the sum of the five-item scores and is between 5 and 25 and determines four social risk categories: (i) no social risk (5 points); (ii) mild social risk (6-9 points); (iii) important social risk (10-14 points); and (iv) severe social risk (15-25 points)35. The reliability and validity of this questionnaire were evaluated by comparing the score obtained on the scale with a reference criterion of an independent, blind assessment by social work experts. It was reported to enable the detection of risk situations and social problems with good reliability and acceptable validity37.

Training set patient cohort

Demographic, diagnostic and questionnaire data utilizing the EVSF items during the rehabilitation and reintegration of patients were recorded and collected at the Institut Guttmann (Barcelona, Spain) from 2007 to 2020. Inclusion criteria for this cohort consisted of adult patients 18–85 years of age at the time of stroke with an ischemic stroke diagnosis who were admitted within 3 weeks of the onset of symptoms, without any previous comorbidities leading to disability, and whose data was recorded within a week of admission and discharge. Exclusion criteria were any of the following: diagnosis of stroke in the context of another concomitant comorbidity (e.g., traumatic brain injury), a previous history of another disabling condition, patients with EVSF questionnaire performed more than 5 months post-injury, as well as more than 5 months stay at the rehabilitation hospital. The authors confirm that this study is compliant with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 and it was approved by the Ethics Committee of Clinical Research of Institut Guttmann. Experimental protocols applied in this study were approved by Institut Guttmann’s Ethics Commitee. At admission participants provided written informed consent to be included in research studies addressed by the Institut Guttmann hospital.

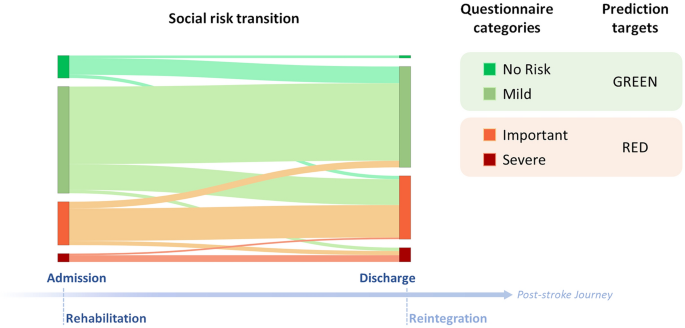

On the basis of available demographic, diagnostic and questionnaire data at the admission of the patient to the Guttmann rehabilitation hospital, the patient cohort consisted of 217 patients and 16 variables for the modelling (Table 2). Although the Length Of Stay variable reported was the actual duration of the patients in rehabilitation from admission to discharge, this variable is estimated by clinicians at admission20. Length of stay varies greatly within Spain; for an older population with mean age of 79.6 ± 7.9 years, Pérez et al reports mean 61.6 ± 45.6 days for 9 facilities in Catalonia-Spain, however, younger patients, such as the patients in this study who are 30 years younger, are reported to stay longer26,38, 39. Hence, the longer length of stay (median 90 days) in this cohort is indicative of the poor functional status of this young, Spanish population (Table 2). The changes in social risk dimensions during patients stay at the hospital were previously examined in Cisek et al.; approximately a third of patients transitioned into another category by improving or worsening their social risk situation, and the majority of patients changed individual risk dimensions35. Since patients can undergo a social risk transition over the course of rehabilitation, the 16 admission variables were used to predict the level of social risk at discharge from rehabilitation in a binary classification, where patients in the no social risk and mild social risk categories were considered as having negligible social risk (GREEN), whereas patients in the important and severe social risk categories were considered as having significant social risk (RED) (Fig. 1). In the 217-patient cohort, there were twice as many male patients as female patients; there was no way to control for this sex ratio in the admitted patients or any gender bias in the referral from acute treatment units. There was a similar imbalance for the social risk classification (Table 2); nearly twice as many patients had negligible social risk (GREEN) than significant social risk (RED) at discharge from the hospital.

No comments:

Post a Comment