Since this seems to promote more red blood cells that could carry more oxygen to the brain, it would seem to be an excellent candidate for hyperacute therapies for stroke. WHOM will do that research?

Does xenon gas improve athletic performance?

Were the Russians on to something in 2014 by huffing xenon gas?

Xenon gas is thought to boost athletic performance.

I have a colleague who is a real sports fanatic who also suffers from repeated (and now chronic) sports-related injuries. A few weeks ago they asked me about the athletic benefits of xenon gas, where it had been discussed in some online forums as a performance-enhancing drug that can also support injury recovery. I’m always surprised (and also not surprised) at the pace of innovation of doping in sport. Xenon is already banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency, so that must mean it’s effective right? I took a closer look at the history and the medical/sports use of this gas.

More that just headlights

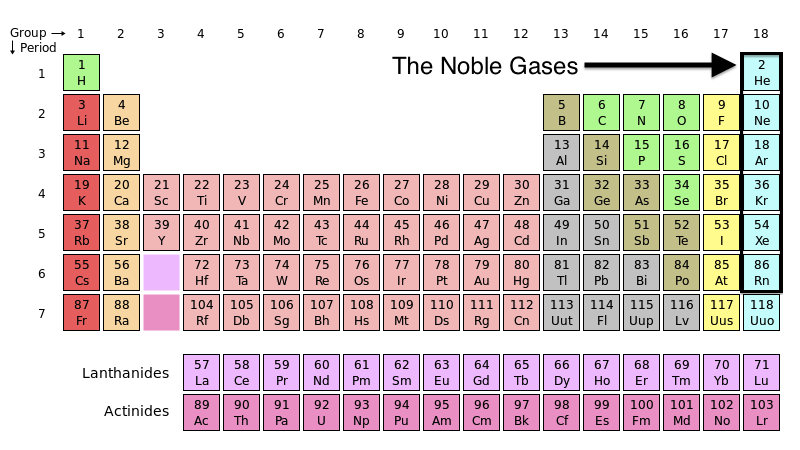

Doping with a gas that you may be more likely to associate with car headlights might seem a bit odd. If it’s been a few years (or decades) since you looked at the periodic table, xenon is a noble gas, way off on the right hand side:

The noble gases. Source.

Noble mean “non-reactive”, in that these elements do not normally form compounds with other elements. Chemically, they are essentially inert and are colourless, odourless, tasteless and non-flammable. Xenon is present in the environment in only trace amounts. However it can be extracted from the air through distillation. As a gas, xenon is bioactive in the body. Xenon is said to be a very effective general anesthetic and more widespread use for this reason seems to be limited to its cost.

In terms of athletic performance, xenon’s asphyxiant properties appear to activate production of HIF-1α, which is a consequence the resultant oxygen deprivation. A secondary effect is erythropoietin stimulation, which promotes the production of red blood cells and consequently the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. If this is the primary mechanism of action to aid performance, then it is akin to altitude training (or training/sleeping in oxygen-deprivation environments.)

Just before the Sochi Winter Olympics in 2014, The Economist declared that xenon was being used in Russia to boost athletic performance:

Xenon works its magic by activating production of a protein called Hif-1 alpha. This acts as a transcription factor: a chemical switch that turns on production of a variety of other proteins, one of which is EPO. Artificially raising levels of EPO, by injecting synthetic versions of the hormone or by taking so-called Hif stabilizers (drugs that discourage the breakdown of Hif-1 alpha), is illegal under the rules of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). Other methods of boosting the hormone, however, are permissible—and that fact has not gone unnoticed by the Russian sports authorities.

After the Olympics (in which Russia did very well, and was also found have implemented a massive doping program), Russian athletes admitted to using xenon. Later that same year, WADA placed xenon (and argon) on the banned substance list, despite not having an effective test, and despite the lack of much evidence it actually had performance-enhancing effects. Since that time, the purported benefits have been explored scientifically.

A 2016 trial randomized 24 volunteers to a xenon/oxygen mix or a control group breathing air, for 45 minutes. Xenon was found to increase erythropoietin level after exposure. A 2019 trial sought to understand the effects of short- and long-term use of xenon inhalation and its effects on blood parameters as well as athletic performance. Through communication with Russian trainers, the methodology was developed which included variations in xenon concentrations in inhaled air. The trial recruited 22 healthy individuals. The data safety monitoring board included experience anesthesiologists who had experience with xenon as an anesthetic, even though the doses were insufficient to induce anesthesia. There were three phases to the trial. Phase 1a, with seven participants, evaluated single doses of three different concentrations of xenon (mixed with nitrogen and normal levels of oxygen) in a non-blinded manner. Phase 1b used the preferred doses from Phase 1 as part of a seven-day treatment protocol. Phase 2 compared four weeks of xenon inhalation to “placebo” gas inhalation in a single-blind manner in recreational runners. Blood parameters and athletic performance were assessed.

The trial found that inhaled xenon cause a small but consistent elevation in serum erythropoietin and total blood volume. However, athletic performance did not benefit. Whether the mixed effects were due to the dosing regimen or perhaps due to counterbalancing effects was not clear:

In conclusion, while acute xenon inhalation of various concentrations caused small but prolonged increases in EPO, short-term daily exposure did not provide superior benefits beyond an acute dose. Although there was no indication of accelerated erythropoiesis in response to xenon exposure, a short-term daily dosing protocol induced significant increases in plasma volume. However, this physiological adaptation was transient and was not observed after chronic (4-wk) exposure to xenon. Xenon inhalation did not increase fitness or improve athletic performance, and, given the adverse symptomology associated with dosing, our findings do not support the use of xenon as an erythropoiesis-modulating agent in sports.

Not snake oil, but unclear effectiveness

I personally find the idea of sports doping both fascinating and sort of horrifying, in that athletes become guinea pigs with their long-term health sacrificed in order to eke out any theoretical advantage. Since xenon was banned by WADA in 2014, some evidence has emerged that painted a mixed but not clearly compelling case that inhaling the gas actually does enhance athletic performance. There is certainly no evidence that xenon has any recreational use, nor is there any evidence that it can help injury recovery. I’m not putting it in the same category as kinesio tape, but it’s probably fair to say that the potential benefits are not worth the risks and the cost, compared to legal (and safer) methods of boosting erythropoietin.

Photo above from flickr user Global Panorama used under a CC licence.

No comments:

Post a Comment